Caption

Until 2018, the ASO did not have the Shaw Grammys; they were in the possession of Thomas Shaw of Austin, Texas, the son of the great man.

It has been a busy summer of construction inside the Woodruff Arts Center. The first and second floors are a hive of activity as the Rich Auditorium is being redesigned.

The front door for the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, facing Peachtree Street, is being reconfigured as well.

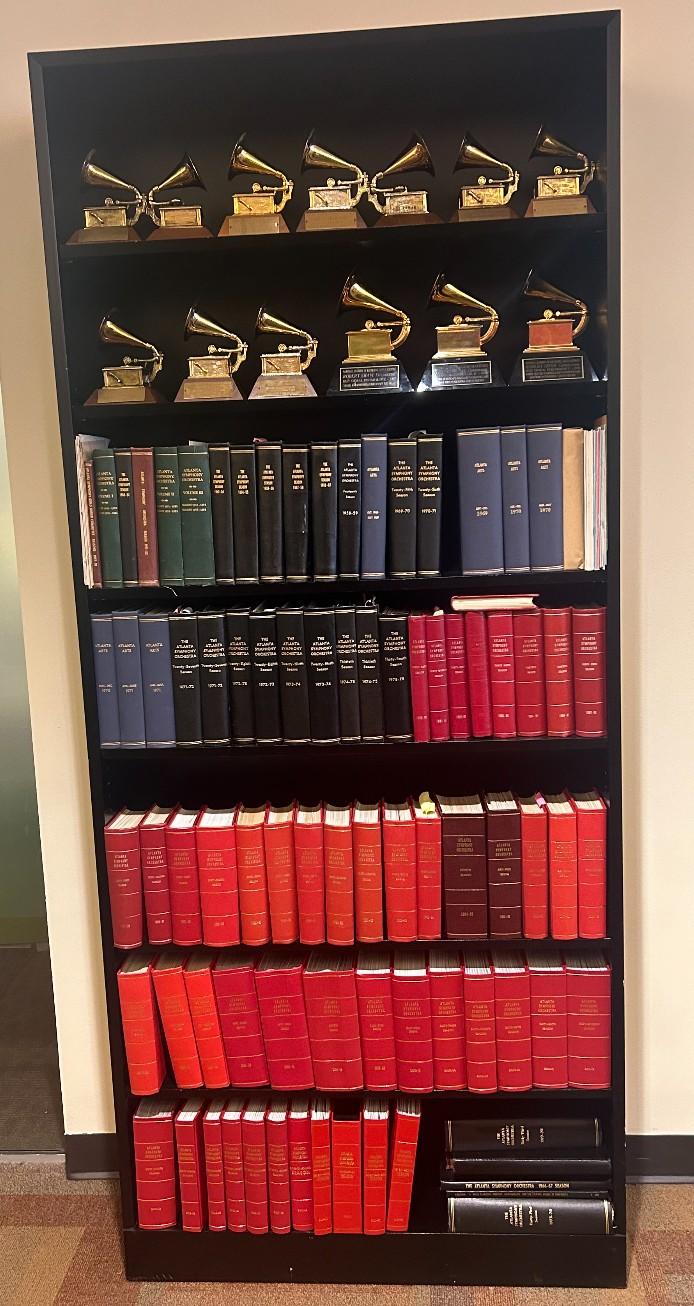

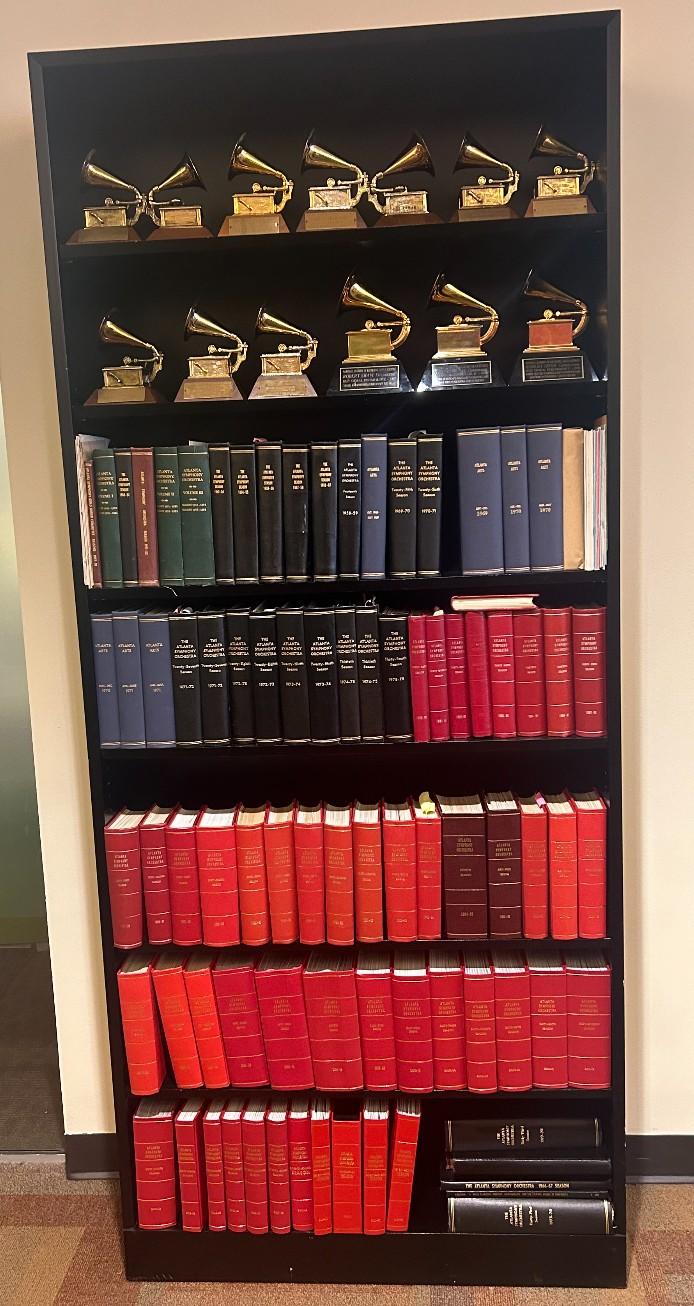

“Once the renovations are finished, we are going to take the collection of ASO Grammys and move them to the new Robert Shaw Room,” said Bob Scarr, the affable, longtime archivist and ASO Research Coordinator. "We've had them on the 4th floor of the Memorial Arts Building, but that is going to change soon.”

The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra has collected 27 Grammys. It's become the generational calling card of this extraordinary group of women and men.

“It was a great collaboration with [record label] Telarc and the ASO over the years,” Scarr said. “I could argue that Robert Shaw was our calling card.”

The great ASO conductor was responsible for 14 of those Grammys; the first coming in February of 1985 for the Berlioz Requiem, John Aler, Tenor.

Until 2018, the ASO did not have the Shaw Grammys; they were in the possession of Thomas Shaw of Austin, Texas, the son of the great man.

The ASO Program Annonator in the 1980s was Nick Jones. He said: “All of Atlanta rejoiced when the Berlioz recording won four Grammy Awards, and the Recording Academy conferred its rarely-given Governors Award upon the ASO and Chorus.”

The Atlanta Symphony had arrived.

Robert Shaw's reaction to the Grammys?

“He could care less; it was all about the music,” contends archivist Scarr.

Until 2018, the ASO did not have the Shaw Grammys. They were in the possession of Thomas Shaw of Austin, Texas, the son of the great man.

Yale had the Shaw papers, but the Connecticut Ivy League school did not want the gramophones.

“Nola Frink was Shaw’s ASO assistant, she stayed in close contact with Thomas over the years and knew he was interested in sending the Grammys back to Atlanta,” Scarr continues.

The first Shaw Grammy is currently displayed at Georgia State University; the others are inside the arts building.

Shaw came to Atlanta in 1967, leaving the celebrated Cleveland Symphony, because he admired Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Atlanta Constitution columnist Ralph McGill.

He was a champion of social justice and civil rights. When he toured the 1960s South, Shaw and his group refused to stay or perform in segregated venues.

Brilliant and mercurial, Shaw astonishingly had no classical or conservatory training — he was self-taught.

When he arrived 57 years ago, Atlanta had few cultural institutions.

Shaw changed everything with the ASO — Grammys, record sales, international notoriety for a city on the rise. Under his baton, the ASO budget rose from $500,000 to $12 million with 93 full-time musicians.

Ms. Frink recalls long days that began at 8 a.m. and ended with the last rehearsal at 10 p.m.

"He was a towering figure; irreplaceable, really," she noted.

And the high point during his tenure, in her opinion?

“The trip to East Germany in 1988 before the fall of the Berlin Wall," Frink declares. "Beethoven’s Ninth never sounded so marvelous.”

Robert Shaw died Jan. 25, 1999, in Connecticut.

He is buried at Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery.

The Grammys will be displayed later this year inside the Memorial Arts Building. The calling card is now complete.