Section Branding

Header Content

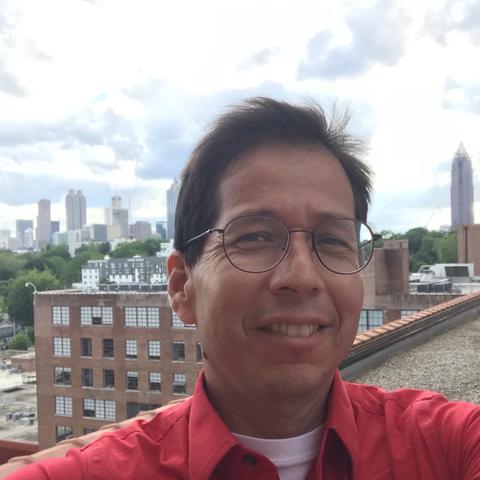

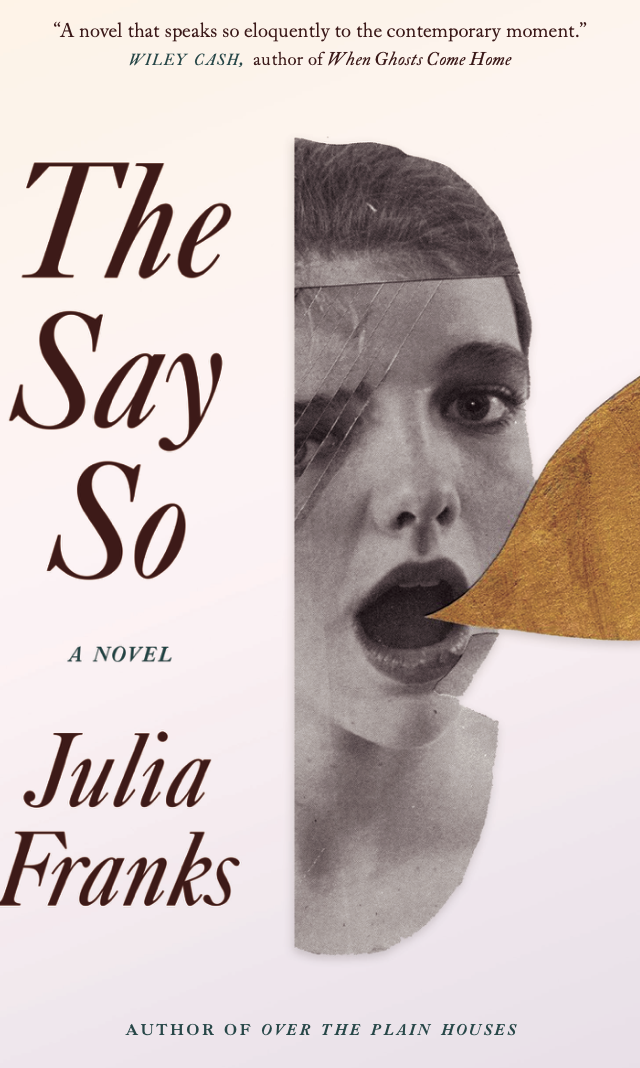

Julia Franks: The Say So

Primary Content

Award-winning author Julia Franks' latest novel is the story of two young women contending with unplanned pregnancies in different eras. After a discussion with Julia Franks, Peter and Orlando share some of their thoughts and insights on "The Say So."

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode:

Orlando Montoya: I mean, I think we should acknowledge we're two men here.

Peter Biello: Yes.

Orlando Montoya: We cannot possibly imagine mommy hormones or anything else.

Julia Franks, Author: And I actually thought the fable was something that was sort of this relic of the 1950s and 1960s. But it's coming back. It's back.

Peter Biello: You may want to do one thing, but it's got these forces against you that are just so strong. And Julia Franks really makes that clear in The Say So.

Orlando Montoya: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia connections hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB Radio. I'm Orlando Montoya.

Peter Biello: And I'm Peter Biello. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings, and the insights behind the stories mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge. Orlando It's great to be in the studio with you again.

Orlando Montoya: We're back at it again one more time.

Peter Biello: One more time. And we're back for another edition of Narrative Edge today, because I wanted to tell you about this new novel by Julia Franks called The Say So. It's about adoption, which I don't think is often addressed in popular books or movies or media in general. Do you know of any popular stories?

Orlando Montoya: I can't think of anything really. Maybe going back into Greek mythology or something like that.

Peter Biello: Yeah, maybe. I mean, I think most recently of — and this is not really recent because it's the 1980s when it came out — is, is The Cider House Rules by John Irving, which is partially about abortion, partially about adoption. There's there's an orphanage involved and abortions in a time when abortion was not legal.

Orlando Montoya: I have at least heard of that one.

Peter Biello: Yeah, it was a popular movie as well. John Irving is the author of that one. Really great book. But this book is is different because it's it's solely about adoption and not abortion. It's The Say So by Julia Franks. It's about two women who give up their children for adoption. One is Edie. And in 1959, in North Carolina, she gets pregnant at age 16 and her parents force her into a maternity home, which is pretty common for, for that day and age. And she wants to keep the baby, but she's forced to give it up for adoption. So I asked Julia Franks to talk to me a little more about Edie.

Julia Franks: I think of her as somebody who's born relatively lucky, you know, great family, good socioeconomic situation. So she's, you know, in some ways is the luckiest of people until she gets pregnant at the age of 16. And then, you know, she does end up in a maternity home and and it's her parents' choice, which is the way it was in a lot of cases. And she doesn't really realize that once she's in that home, she's already on this track where she doesn't really get a vote anymore.

Peter Biello: And that's why the book is called The Say So. It's about who gets the say so when it comes to the choice, the choice of whether or not to carry a baby to term. And if you do give birth, whether or not to keep it. Edie does not really have a choice in this case.

Orlando Montoya: Sounds like she's a prisoner of some kind.

Peter Biello: Yeah. She goes into this maternity home. Her parents are paying for this. And at every turn, at this maternity home, she's questioned about why she wants to keep this baby. And underlying the question is like, you're not ready to be a mom. Why do you want this baby? She's pressured in every which way to give this child up for adoption. Even a psychologist is enlisted to sort of give her this therapy session where the therapist basically says, well, you want to keep this child despite being so young, you clearly aren't rational. And therefore, if you're not rational, you're not fit to be a mother. So really, you ought to give up this child.

Orlando Montoya: It's like a Catch-22.

Peter Biello: Yeah. And if you're 16, 17 years old in this maternity home, you know, with all these adults around you sort of pressuring you in a particular way, you may want to do one thing, but it's — you get these forces against you that are just so strong. And Julia Franks really makes that clear in The Say So.

Orlando Montoya: And so what happens to her, Edie?

Peter Biello: I won't give up too much. But the crux of the story here is that adoption is not simple or easy. And Edie struggles with that decision both before it and after she's forced to give this child up for adoption. Really wasn't her choice. And that that that kind of makes it worse for her in a way, because the choice wasn't hers.

Orlando Montoya: Now, you said there were two women. Who is the other one?

Peter Biello: Oh, yes. That would be Meera. Meera is the daughter of one of Edie's high school friends. That's sort of how this novel is linked together across generations. She gets pregnant in her 20s, and this is the early Roe v. Wade era, so that in 1980. So she has the option for abortion, but she chooses adoption. I mean, there are several points in this novel where people like, "I thought you were pro-choice," and she's like, "I am, but I've made this choice to give up my baby for adoption."

Orlando Montoya: That's the definition of pro-choice.

Peter Biello: Right. Right. You get to choose.

Orlando Montoya: You get to choose.

Peter Biello: And she did choose. She, she chose adoption. I spoke with Julia Franks about Meera's story in particular, and she said it was kind of based on her own life.

Julia Franks: I did have an unplanned pregnancy in college, and I did for many reasons, complicated reasons, some having to do with naivety, some having to do with overconfidence — like, I was an overconfident kid. I chose to have the baby and give them up for adoption. You know, I felt "well. I can bring this child to term. You know, finish my senior year, continue my three nights a week waitressing job and, you know, figure out what I'm going to do with the rest of my life." I thought, "well, I mean, it's not going to be easy, but doable, right?" So —

Peter Biello: You think you think it's doable and then reality comes crashing in.

Julia Franks: Oh, it's so it was so much harder than I ever imagined. And it's not. And I, and I don't mean like the logistical parts, which is what everybody thinks of or the physical part or the actual pregnancy. Just has more to do with, in my case, like my own hubris, you know. Like, I didn't take emotional risk into account. I didn't take physical risk into account. I didn't take loss into account and I didn't really take grief into account. Certainly not the kind of, you know, decades-long grief that that most women experience.

Orlando Montoya: When she's talking like that. I can see how this book could get very political very quickly. Is this book political and have kind of overtones of what choices people should make?

Peter Biello: You know, it could have gone that way, but it's not really engaging in policy. It's diving into the emotional fallout from A) the lack of agency when women can't choose without being pressured, and B) what happens emotionally when women have a choice? The choice is never easy. There's always some kind of sway happening somewhere. Franks pointed out to me when we spoke what she calls the fable of adoption that's spoken about quite a bit when people when politicians discuss adoption.

Julia Franks: So there's this fable that has to do with adoption, which, it has two parts, actually. The first part is that if you have an abortion, you'll be traumatized for life. And the second part of the fable is that if you release your child for adoption, you'll be some kind of hero, right? And I would say both parts of that fable are 180 degrees wrong. And I actually thought the fable was something that was sort of this relic of the 1950s and 1960s, but it's coming back. It's back. It's already back.

Peter Biello: You say a fable that's being told to pregnant women as they're trying to make up their minds on what to do?

Julia Franks: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Peter Biello: And who's telling this fable? Is it is it the family members? Is it social workers? Clinicians? Everybody?

Julia Franks: Not everybody, but people in all those groups. You know, certainly, you know, evangelical churches are big proponents. But, you know, the most obvious person is Amy Coney Barrett, Justice Amy Coney Barrett. You know, she's said, you know, women don't really need to have abortion rights because they have the option to relinquish their children for adoption. I don't know how many pregnant women you've been around, but if you have been around some, you know that there's this hormonal transformation that happens to women when they're pregnant. They, you know, they get all these mommy hormones sort of dump into their system. And those chemicals, those hormones help them create a bond with their child in utero. And you're going to get those hormones whether you want them or not, you know, And it is pretty naive, and I include myself in that. It's pretty naive to think that you won't be affected by them. And I mean, Justice Barrett should know better because she's been through pregnancy. She should know.

Peter Biello: Have you sent her a copy of the book?

Julia Franks: No, I haven't. I would love it if she would read it.

Peter Biello: So to your question, Orlando, is this book political? Could it be political? I mean, I suppose we could leave it to our imaginations, right? What Justice Amy Coney Barrett would say about this.

Orlando Montoya: But she's certainly political right there.

Peter Biello: Yyeah, definitely got political in the conversation. But I think what gives this book the narrative edge, right? Is that it put me as a reader, you know, someone who's never been pregnant, who's never been faced with this decision —

Orlando Montoya: Yeah and I think we should acknowledge we're two men here.

Peter Biello: Yes.

Orlando Montoya: We cannot possibly imagine mommy hormones and everything else.

Peter Biello: Absolutely right. So but this book puts you in that as close as you can get to understanding that perspective. I mean, it puts you in Meera's position. It puts you in Edie's position. You sympathize with them. You feel what they feel. And I think that's what good fiction is supposed to do, right? It's supposed to help you walk a mile in somebody else's shoes. So — so thanks to The Say So, I feel like I have a little bit of insight into what some women faced back in the 1950s and 1980s when they had had this decision or didn't have the decision.

Orlando Montoya: So that's The Say So.

Peter Biello: That's The Say So.

Orlando Montoya: It's by Julia Franks. Thanks for telling me about it. I want to go out and read it now.

Peter Biello: Happy to do it. Thanks, Orlando. Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at GPB.org/NarrativeEdge.

Orlando Montoya: You also can catch us on the daily GPB News podcast Georgia Today for a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and for all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts.