Section Branding

Header Content

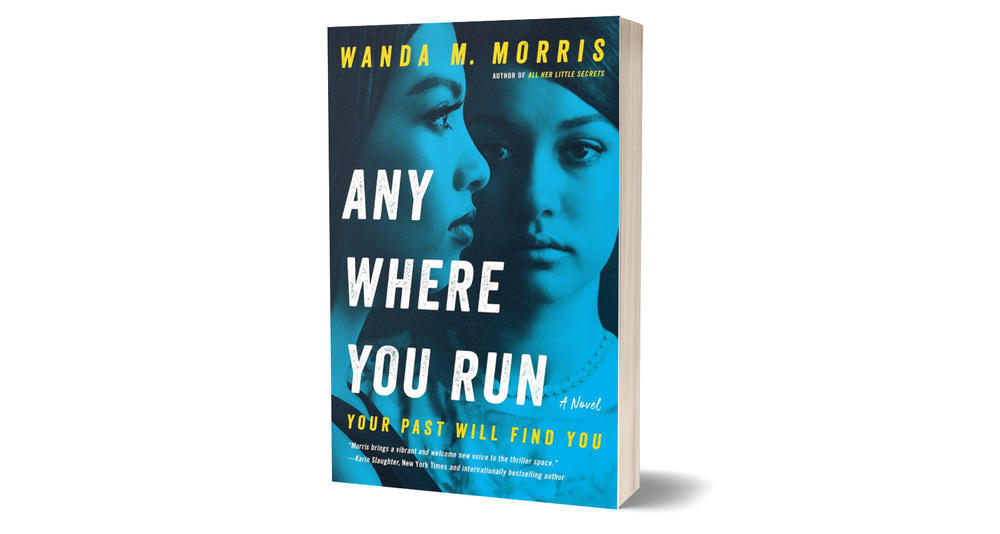

Wanda Morris: Anywhere You Run

Primary Content

It’s the summer of 1964 and three innocent men are brutally murdered for trying to help Black Mississippians secure the right to vote. Against this backdrop, twenty-one-year-old Violet Richards finds herself in more trouble than she’s ever been. Peter and Orlando dive into Anywhere You Run in this episode and talk with Atlanta-based author Wanda Morris.

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode.

Orlando Montoya: You really get into the characters minds, you get into their hearts, you're invested in them, and you're invested into this larger story of how each of these people got into their situations.

Wanda Morris: I went to the library and I told them, "Here's what I want to write about." And he said, "I got you." And they just kind of opened up this wealth of materials.

Peter Biello: Do the evil ones die? I must know.

Orlando Montoya: I will say that I am personally satisfied with the ending.

Peter Biello: Aw, that's not really an answer.

Orlando Montoya: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia connections, hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB radio. I'm Orlando Montoya.

Peter Biello: And I'm Peter Biello. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings, and the insights behind the stories mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge.

Peter Biello: All right, Orlando, it's time to talk again about books. What do you have this time?

Orlando Montoya: Well, this time I have a work of fiction. It's called Anywhere You Run by Atlanta-based writer Wanda Morris. And it's part coming of age story, part whodunit. The action is high stakes. There's a lot of twists and turns. And when I was reading it, I sort of got the idea that I was watching these people, getting emotionally involved in the characters. And I kind of just wanted to reach into the story and lead these characters to to safety.

Peter Biello: Lead them to safety. So who's in danger? What's the danger here?

Orlando Montoya: Well, we have two main characters. They're sisters, Violet and Marigold. And this story is set in 1964 Jackson, Miss. And these two sisters are black women, young black women, 20-21. And so there's a lot of danger sort of inherent in that situation. But in the opening chapters, we find out that Violet has killed somebody and Marigold is unmarried and pregnant. And so they're both on the run.

Peter Biello: Wow, okay. So if they're running, someone's chasing them, right? Who's chasing them?

Orlando Montoya: So the person who is chasing them is a young, poor white man called Mercer. And he's kind of in it for the money. He's a hit man. And he's trying to find these two young women. One has fled to a small town in Georgia, Violet. She's gone to a small town in Georgia, which is identified, by the way, as in Taliaferro County, the one we all love, the spelling of.

Peter Biello: Everybody loves Taliaferro County.

Orlando Montoya: And the other one, Marigold, goes to Cleveland, Ohio. So Mercer is looking to find and kill Violet. And, you know, one of the things I like about the way the story is set up is that each chapter is kind of really short and each character narrates an individual chapter.

Peter Biello: And is it giving too much away to say why he wants to kill Violet?

Orlando Montoya: He wants to kill Violet because another man, Dewey, was having an affair with Violet, and Dewey was a white man. Do you want me to get into all this?

Peter Biello: So — so racially motivated, misogynistic hate. They want to kill her because of that.

Orlando Montoya: Yes. Well, Mercer is really in it for the money. I kind of see Mercer as a character as he is racist in the way that sort of all young, poor white men in that era were racist. He doesn't come across to me as — well, I guess he would be evil if he's trying to kill somebody, but —

Peter Biello: So she humanized — does Wanda Morris kind of humanize him, even though he's a terrible person?

Orlando Montoya: Wanda Morris humanizes everybody in this story. That's why I like the story, because you really — you really get into the characters' minds. You get into their hearts, you're invested in them, and you're invested into this larger story of how each of these people got into their situations. These are societal problems, the Jim Crow South problems that we're still dealing with today. And that's why Wanda Morris wanted to write the book.

Wanda Morris: This story kind of came out of actual headlines despite the fact that the book is set in 1964. But I started this project right after we'd come through the 2020 election, and there was a lot of talk about the big lie and election fraud. And I thought to myself, "How did we get here and why are we still grappling with the same issues that we were grappling with with 60 years ago?" And so I knew that I wanted to tackle those issues. Going into a 1964 historical setting was a little unique, but I'm glad I took on the challenge.

Peter Biello: Wow. Okay, so what issues is she talking about there?

Orlando Montoya: Well, we've got abortion. Two of the characters in the story have an abortion. We have miscarriage. One of the characters has a miscarriage. Uh, there's racism, of course, all through this whole story. There's class power. As I mentioned, Mercer, this — this hit man, he's of the lower white class. And he is really being manipulated by these evil — these are the pure evil ones, Dewey and Olan. And then there's voting rights because one of the characters is a voting rights activist. And the whole story starts with a — with the killing of voting rights activists. There's domestic abuse and it's all just rivetingly told and despite all these problems, I want these characters to succeed.

Peter Biello: So how does Wanda Morris make the story so riveting?

Orlando Montoya: As I said, well, there's empathy. She's talking about them as they're human beings. There's a lot of back story, as you can imagine at this. The chapters are short, but I think there's like 50-some chapters. So there's a lot of sort of back story into all the characters and to why they're sort of acting the way they do. And there's a lot of nuance and gray areas. You know, I don't think any of these characters, even Violet and Marigold, are totally pure. They all make bad decisions. And so you get these gray areas, and that's where Wanda really succeeds.

Wanda Morris: First and foremost, I want to tell a story that's engaging and entertaining because, you know, people go and spend 20 bucks for a book. They want to be entertained. But I also — I personally like to read books that I learn something from. And because this issue was so important to me. I am a descendant and a beneficiary of the civil rights movement. So I knew that I wanted to weave this issue into the story. I tried to make sure that my characters are infused with issues that the story tackles. So, for instance, there is a woman who is gay in the story, and we see her story line. Of course, there are Violet and Marigold who have their own issues around attack of women as well as, you know, being pregnant and unmarried in the '60s. And so I make sure that my characters carry the storyline and they carry the tough issues.

Peter Biello: Sometimes when I hear about a character being infused with the kind of issues that their lives are facing, that they become sort of like a caricature of that issue and not — not a real human person. So I'll ask you again: Like, is — does she manage to get away from just making the stereotype of a particular issue or are they actual real people who happen to be facing this particular thing, whether it's abortion or racism or what have you?

Orlando Montoya: I would say there was probably only — if I had to say it truthfully — there was probably only a couple of characters that were sort of wooden and I could have done without, and that they were sort of two-dimensional. And the pure evil characters, they were — they were pure evil. And we don't see them a lot in the story. But the main characters, Violet and Marigold and Mercer, are all very well, well rounded and well-described..

Peter Biello: Yeah. And I would say, to be fair, sometimes books need the pure evil character. They just don't really hold up as a main character.

Orlando Montoya: Well, there's not going to be any action.

Peter Biello: Right. Where you're watching a cartoon all of a sudden.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah.

Peter Biello: You know. Well, all right. Getting back to that storyline, you said that these two sisters were running from a hit man. One ended up in Georgia, the other in Ohio. Where does the story go from there?

Orlando Montoya: Well, I think sort of one of the main turning points in the story is when Marigold decides to leave her husband in Ohio and join Violet, who now goes by Vera in this little town in Georgia. And sort of when you're seeing this or reading this — believe me, I see it in my mind — but when you're reading this, you get the sense that it is not going to go well once this happens, because Mercer is after Violet and and Mercer is following Marigold to get to Violet. So you, you know, it's not going to go down very well at some point. And you just think, how are they possibly going to survive this?

Peter Biello: Hmm. So how do they survive?

Orlando Montoya: Not going to tell you!

Peter Biello: Ahhh!

Orlando Montoya: Wanda Morris leaves the denouement — the the final conclusion — to the final chapters. And all I'll say is that four people end up dead, in addition to the three who are dead in the first chapter. Because, as I mentioned, the story starts with a civil rights killing, the killing of three young civil rights workers in rural Mississippi. And so over the course of these 50-some chapters, she's leaving clues. And this is something from her lawyer days because I didn't tell you yet, but she used to be a lawyer.

Peter Biello: Okay.

Orlando Montoya: She actually quit her lawyer job to become a writer. And so she — she uses that sort of storytelling, I think, that she got from her legal career. And I asked her how she transitioned to make that leap from lawyer to author.

Wanda Morris: It wasn't as hard as I thought it would be. You know, I think I always just thought "I'm a lawyer." But at the heart of it, I think I've always been a storyteller, as you mentioned. And so once I started to write these stories, I felt this sense of engagement and purpose that I hadn't found in a long time in my legal practice. It's interesting because I tend to write about stories about issues that, you know, make me sad and make me mad and make me crazy. And interestingly enough, those issues make other people mad and sad. And I think that has what — that has been, what has, has driven readers to my books.

Orlando Montoya: That's one thing that I think gives the story the Narrative Edge. It has sort of a lawyerly manner of building up a story layer upon layer, step by step, and you're really invested in these characters.

Peter Biello: Okay, so what else can you say to recommend this book?

Orlando Montoya: Scene setting. Scene setting. Lots of — like music from the time. You can feel the dirt, you can smell the earth, the clothing, the language that she uses. And she's talking about like buses and diners and payphones and people making reverse phone call, reverse charges. Remember, reverse charges?

Peter Biello: I'm too young for that. Sorry.

Orlando Montoya: Well, I could really see this story. And I asked her how did she do that?

Wanda Morris: I always like to give a shout out to the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American history and culture, located right here on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta. And once I had settled on the issue, I knew I wanted to tackle voting rights. And once I settled on that issue, I went into that library and — I went to the librarian and I told him, "Here's what I want to write about." And he said, "I got you." And they just kind of opened up this wealth of materials, books and papers, particularly around the Freedom Summer, as well as the murder of the three young civil rights workers. I also did something that kind of helped me get into the mindset of the 1960s, and that was to listen to a lot of music from the 1960s. If anyone goes to my website, there's a playlist for the book and there's all types of music. I read a ton of magazines: Tan, Ebony, Life because those gave me a sense of the way people talked in the '60s. The way people talked in the '60s is very different from the way we talk now. And so I wanted to lean in that and make sure that the reader had an ear for what the 1960s sounded like. So there was a wealth of information that I tapped into.

Peter Biello: So I really want to hear some of these words. Was she using different words or was the dialog sort of authentically 1964?

Orlando Montoya: It was authentically 1964. So she was using words that we don't use.

Peter Biello: Okay, well, do the evil ones die? I must know.

Orlando Montoya: I will say that I am personally satisfied with the ending.

Peter Biello: Aw, that's not really an answer, but a dodge.

Orlando Montoya: Even — you know, there were a couple of twists and turns that I would personally not have written. But that's the beauty of fiction. You know, it's not my book. It's Wanda Morris' book. And I think the difference between, you know, my book in my head and her book that she has written is where you sort of find yourself. And that's the beauty of reading. You know, you you read books to find yourself.

Peter Biello: Well, that's a great place to leave it. The book is Anywhere You Run by Wanda Morris. Orlando, thanks for telling us about it.

Orlando Montoya: Thank you. I look forward to the next one.

Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand-new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at GPB.org/NarrativeEdge.

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the Daily GPB News podcast Georgia Today for a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts.