Section Branding

Header Content

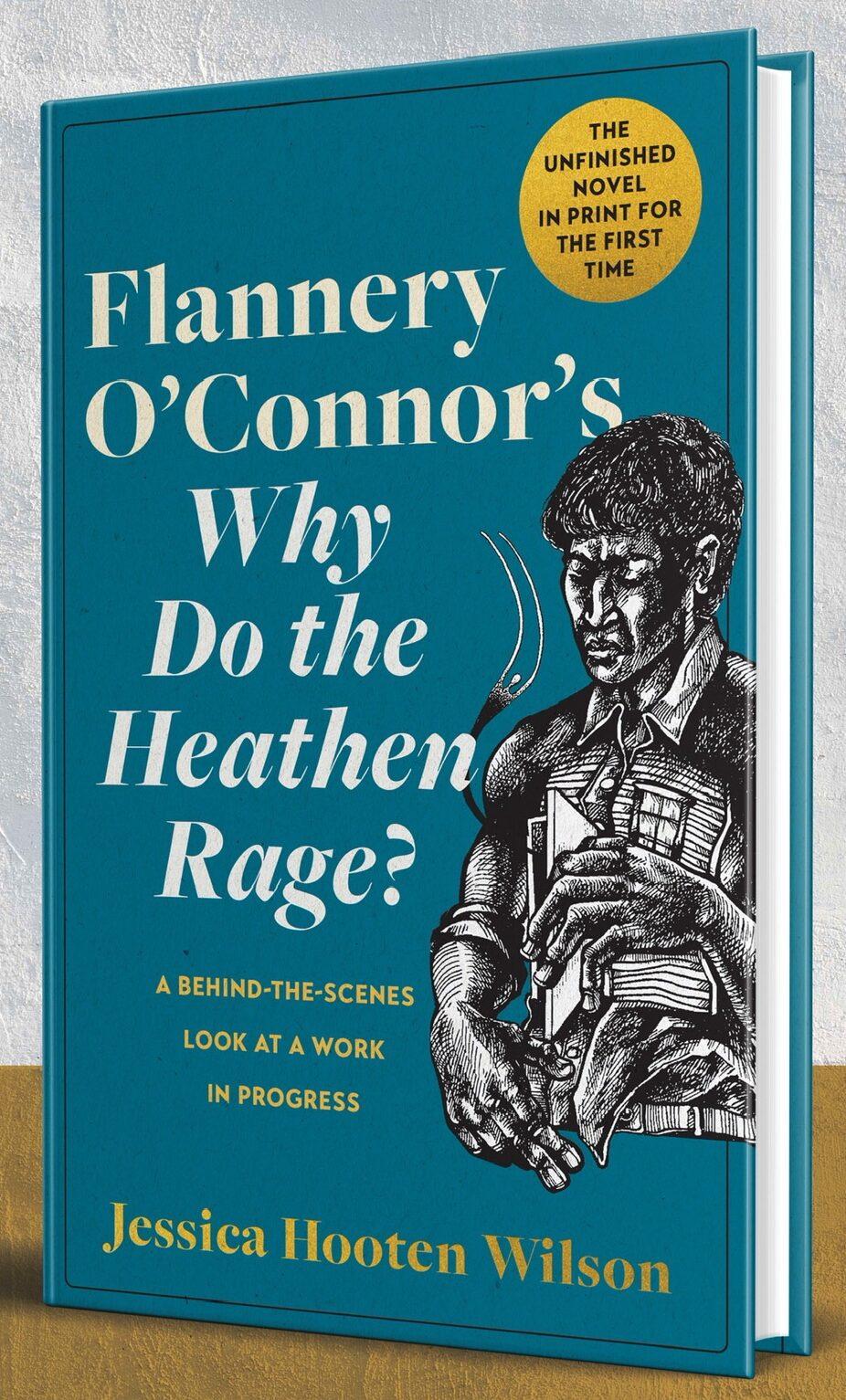

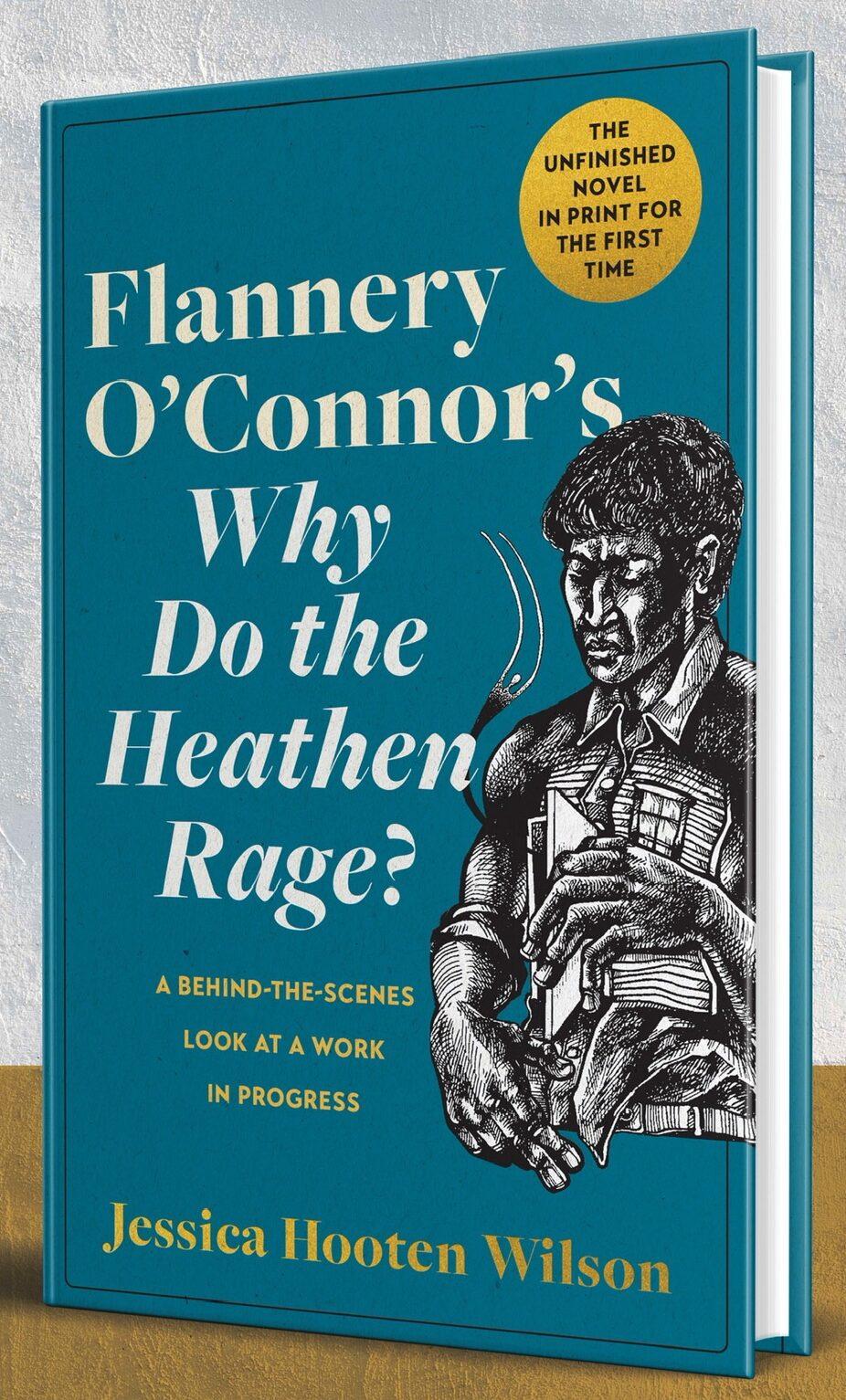

Flannery O'Connor's Why Do the Heathen Rage? A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress by Jessica Hooten Wilson

Primary Content

When celebrated American novelist and short story writer Flannery O’Connor died at the age of 39 in 1964, she left behind an unfinished third novel titled "Why Do the Heathen Rage?" Scholarly experts uncovered and studied the material, deeming it unpublishable. It stayed that way for 40 years. Until now.

Join Peter and Orlando as they explore, along with author Jessica Hooten Wilson, the lessons and the what-might-have-beens of "Why Do the Heathen Rage?"

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode.

Orlando Montoya: She's dark, she's sharply witty, she's sassy. She writes about misfits and outsiders, and her work can be interpreted as deeply spiritual.

Jessica Hooten Wilson: So getting to see her in process is what I'm hoping this book shows and gives people more, more freedom to read her generously.

Peter Biello: I have to say I hard disagree with where to start. Start with the death. Start with the death stories for Flannery O'Connor.

Orlando Montoya: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia Connections, hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB radio. I'm Orlando Montoya.

Peter Biello: And I'm Peter Biello. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings, and the insights behind the stories mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge. Hey, Orlando, what book do you have for me today?

Orlando Montoya: Today I have a book about Flannery O'Connor, one of Georgia's most celebrated writers. She was born in Savannah. She wrote most of her famous works and died in Milledgeville. The book is called Flannery O'Connor's Why Do the Heathen Rage? A Behind the Scenes Look at a Work in Progress by Jessica Hooten Wilson. And I'm very excited to talk about Flannery since I spent 23 years in Savannah, and O'Connor is very much celebrated in that city.

Peter Biello: Did you do any stories about O'Connor when you were a reporter for GPB in Savannah?

Orlando Montoya: Of course I did many stories. I went to her childhood home in Savannah. I went to her family farm in Milledgeville, where she wrote. I even visited her grave in Milledgeville. I interviewed one of her biographers and just lots of people in Savannah who are very passionate about O'Connor, and I know she has passionate fans all over the world.

Peter Biello: Do you count yourself among those fans?

Orlando Montoya: I find — myself, I find O'Connor a little difficult, maybe for reasons that we'll get into a little bit later. But many people love O'Connor. She's dark, she's sharply witty, she's sassy, she writes about misfits and outsiders, and her work can be interpreted as deeply spiritual, touching on themes like mystery and grace.

Peter Biello: Like Catholic, right? She's one of the big Catholic writers.

Orlando Montoya: Oh, very Catholic. Very, very Catholic.

Peter Biello: There's Andre Dubus and then there's Flannery O'Connor.

Orlando Montoya: No, there's Flannery O'Connor, and then there's Andre Dubus.

Peter Biello: And maybe Graham Greene. Well, I remember in MFA school, just as an aside, the teaching technique and whatnot about creating just beautiful prose, one of the things one of my professors did, they took a page out of one of the classic Flannery O'Connor stories. Right? Either It's A Good Man is Hard to Find or Good Country People — one of those —and just highlight wherever she references a facial expression. And through those facial expressions, she was able to convey so much about her character.

Orlando Montoya: And so you're a fan.

Peter Biello: I'm a huge fan stylistically, just the tension she's able to build in these stories. She was a gift. She was an absolute gift. So how are we getting a new book from her when she's been dead since 1964?

Orlando Montoya: Well, the book we're getting here is the story of one of her unfinished stories. So, like many writers, she had sketches that she was working on. She played with some ideas for characters, some ideas for plot in these sketches. And she kept these sketches or ideas, to herself until, obviously, she died.

Peter Biello: And she died at a young age. She was, like, 39.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, she died at 39 years old. She had lupus and was crippled for many years before she died. And then her unfinished manuscripts were kept in an archive where decades later, scholars started digging around and finding things. One of those scholars is Jessica Hooten Wilson, who is an Endowed Chair of Great Books. I love that title at Pepperdine University. And one of those stories is called "Why Do the Heathen Rage?"

Jessica Hooten Wilson: One of the things I tried to make sure and highlight on the front is that it's unfinished and it's a work in progress, because the novel is not done, it's incomplete. And what she ended up doing is writing the same episode so many different times in the 400 pages that she left us, that we — we really just get a bunch of background of these different characters. We get to see that she was working through who they were going to be and how they were going to come together. But the plot doesn't take off. There's no catalyst for action. You're actually on the verge of something happening and then it doesn't. And you're kind of always left hopeful of what could have been with the story, rather than getting to see what was.

Orlando Montoya: So I'm going to describe this book like an archeological excavation. We get fragments, and then Wilson takes us through those fragments: where they come from, where they might have gone in an eventual novel if she had lived, and how they fit into the overall scholarship of O'Connor. And believe me, when we talk about O'Connor, we have a lot of scholars, people who have made their entire careers about writing about O'Connor.

Peter Biello: So what kind of fragments are we talking about in terms of character and plot here?

Orlando Montoya: So we have two main protagonists, Walter and Oona. Walter is a young man living on a Southern farm. He's an intellectual, and his mother describes him as fairly useless around the farm. He starts writing letters to strangers to amuse himself, and he ends up in a correspondence with Oona. Now she is a Northern liberal civil rights activist, and in his letters to Oona, Walter pretends to be Black and pretends to fall in love with her. His idea is that he's going to test her open-mindedness, test her commitment to equality, somehow, at some kind of rendezvous, which never happens because the story's unfinished. Now, to me, the whole thing is kind of creepy.

Peter Biello: Creepy? Why?

Orlando Montoya: Well, to me, it seems like this is heading to some sort of violent episode.

Peter Biello: Not uncommon in Flannery O'Connor stories.

Orlando Montoya: O'Connor always gets to violence somehow. Lots of people die. So I was kind of expecting that. But in the end, nothing really happens. Walter and Oona never meet. The most we get in terms of plot development is an episode in which Walter is sitting on a rock and he has some kind of spiritual revelation.

Jessica Hooten Wilson: In her other work, she has these more violent episodes where people are scandalized by the truth. So you get gored by a bull, or you get, you know, hit in the head with a psychology textbook, right? These are some of her quintessential episodes. She said that in this book, she wanted to talk differently to the reader. She wanted God's voice to be kind of a still, small, quiet voice instead of a loud roar. He didn't want to smack people upside the head. And so Walter is sitting there and kind of coming to a realization that maybe he actually believes all the things that he's been reading. Maybe the truth is outside of himself, and he can't stand above it, because that's what Oona's doing. From his perspective, she's standing in the place of God, and he too was there with her. And so he comes to kind of this realization. Now we don't get to see what happens from there. It's my idea that I think he would have become a holy fool. I think she would have written an entire novel in which the salvation story comes at the beginning, and it's not the epiphany at the end. And then we would have got to see Walter's character as he kind of lives this out. I think that's what she was trying for, but she obviously doesn't get there. We don't get past this episode on the rock.

Peter Biello: So is Walter supposed to represent the segregationist South while Oona represents civil rights? Seems maybe that's simplistic, but is this O'Connor's take on race and civil rights here?

Orlando Montoya: We don't know. We don't know because it's unfinished. But Wilson certainly thinks this could have turned into O'Connor's attempt to tackle race. O'Connor, as you might know, can be very problematic on race. She was a white woman in the South who lived from 1925 to 1964. There was a widely circulated essay a few years ago titled "How Racist was Flannery O'Connor?" And if you're interested in that aspect of O'Connor, you might start there. But in these fragments of "Why Do the Heathen Rage?" her characters do use the N-word. They describe Black people in unflattering ways. She just could not imagine any other way of living or imagine how Black people think.

Jessica Hooten Wilson: Flannery wrestled with who knows what. You know, she always lists out people that she knew in real life. "Who knows what they think? Because I'm not Black, how do I get into their minds well?" And I had a friend early on who I was reading this material to, and he said, "that's — that's problematic. She should know enough about humanity that she's able to have other people's perspectives, even the Black perspective, and try to write from a human standpoint. What, how are we all related, rather than dividing us up too much? Now, Flannery did not have enough perspective, I think, to do that at the time. She's living in a very segregated world. And so even some of her greatest admirers from African-American scholars like Hinton Owls talks about how, you know, she caricatures them, she makes them into, she makes when two Black people are talking to each other, she just didn't know how that conversation would really happen. She only knew how two Black people would talk when a white woman was in the room, because that was her experience, and therefore she doesn't portray it with a reality that it deserved.

Orlando Montoya: So I'd like to think that this story would have become Flannery's statement on race, that she might have come down on the right side, and that it would have clarified a lot of our doubts about Flannery and race. But it's also possible that she could have just ended up making some other point.

Peter Biello: Like, well, what other point?

Orlando Montoya: Religious.

Peter Biello: Oh, okay.

Orlando Montoya: A religious point. I mean, her entire body of work is just oozing, as you said, with this Catholic sense of the world. And so there's a reason Catholics just love Flannery. And to me, when I read Flannery and this story's no exception, there's just a lot of judgment, from everyone to everyone. And so that's why I kind of find her kind of difficult. Her pages are just dripping with judgment, this Catholic sense that there's going to be a reckoning and you better be on the right side. And these fragments are no different.

Jessica Hooten Wilson: She has characters who talk down to people. So judgment is a key concern of hers that the character she's dealing with, they're judgmental, and she's always expecting that they're going to have a comeuppance. All of her work usually ends with a moment of self-revelation, and that self-realization, or self-revelation is when she says, you come up against truth and you have to judge yourself against the truth and what you are not, and see how far it as you are from what's true. So a lot of these characters are living in a place where the truth is beneath them. They are standing above things and they're looking down at the world. They're looking down at others. They are very judgmental. And so the reason there's a lot of violence in Flannery is she wants to kind of smack sense into them. She wants to knock them off their pedestal and show them a different way of seeing the world where they're not on top of it.

Peter Biello: Did you get the sense that Flannery O'Connor sort of agreed with Walter's perspective, in the sense that, you know, Walter is challenging Oona to say, oh, you know, "How committed to this are you? Can you love me as a Black man?" Did you get the sense that she was, like, Walter is on the right track? He's going to call out some hypocrisy? Or is she saying, you know, Walter's going to get his comeuppance because it's not for him to — to judge anybody or maybe, you know, a different option I haven't just named.

Orlando Montoya: I'm hoping for Walter getting his comeuppance. That's what I was hoping for. Or I could have easily saw it as turning very violent and Oona dies.

Peter Biello: So corresponding with a stranger, you know, it's as dangerous then as it as it can be now.

Orlando Montoya: You know, that's — that's why I, you know, the book is just — it's just so — it's just incomplete.

Peter Biello: It strikes me that it seems that she's really struggling here with this one. And I wonder if she struggled just as hard with the short stories that we know today. You know, the ones that are so widely anthologized or did those kind of fall out of her head whole? Or her novel Wise Blood, right? Like, did she struggle with Wise Blood just as much?

Orlando Montoya: I think that's a question for a scholar, but I'm sure that, you know, she was in progress with all of those stories the same way she was in progress with this one.

Peter Biello: Well, so, seems like you can read between the lines to some extent. You're you're not an O'Connor superfan, Orlando, but you are a superfan of this book.

Orlando Montoya: I am, I really like the book. It helped me to fill in a lot of the things that I didn't know about Flannery. Certainly I admire the scholarship that went into it, the uncovering, the excavation, the way it's presented. It's not fanfiction. So she, the author, could have gone and taken an unfinished story and pretended to be O'Connor. She did not do that. She presents it as best she can, given the fact that O'Connor died. And so that's what I think gives it the Narrative Edge. But I will say that this is not the place to start with O'Connor for the uninitiated.

Peter Biello: I yeah, that this does not sound like that place.

Orlando Montoya: I lived in Savannah for 23 years — and I think at this point, every time I say back in Savannah, you should get like $5. — But, but, but I lived there. I read her stories, and even though I'm not a super fan, I have a basic understanding of O'Connor. So if you don't, maybe pick up another O'Connor. And I think Wilson agrees with that.

Jessica Hooten Wilson: I agree that this should not be the first thing someone who is going to read Flannery O'Connor would read. Instead, a lot of times I recommend — I think I recommend this in the book — people should be reading Parker's Back or Revelation to start with. And really kind of go in more gently with Flannery, with characters who don't die before they start trying to read the characters that do die. But once you start reading Flannery O'Connor stories and you get more familiar with them, I think you'll understand why this material matters. Because it — it reminds all of us that we are in process, that writers are all in process. And I also hope it gives people the pleasure of seeing that Flannery was growing and changing, like all of us are. I would hate to be judged now by something I wrote when I was 20, or something that I said or thought when I was 20. In the same way, man, imagine if Flannery would have lived to be 60 or 70. She might hate to have been judged by everything she wrote in her letters in her 30s. So getting to see her in process is what I'm hoping this book shows and gives people more, more freedom to read her generously.

Peter Biello: I have to say I hard disagree with where to start. Start with the death. Start with the death stories for Flannery O'Connor. A Good Man is Hard to Find. The chilling last page of that story — whew. Start there. Go ahead. You'll fall in love, I promise you.

Orlando Montoya: The Habit of Being.

Peter Biello: Habit of Being. Okay. Yeah. Nice, meditative.

Orlando Montoya: That's a little bit more my my line.

Peter Biello: One of the things she said about writing always rings in my ears. It's — I might be misquoting it, but she said a writer always writes to their level of intelligence, whatever that means. I think for someone in his 20s, when I first heard that, the message was, don't try to be smarter than you actually are. You're good.

Orlando Montoya: She has so many. She has so many wonderful quotes. Yeah, and they're frequently on T-shirts and coffee mugs. And her, her face is just — her face is always scowling. You ever notice that, like, when she's depicted?

Peter Biello: With the peacocks, right?

Orlando Montoya: Yeah.

Peter Biello: She looked pretty happy with the peacocks.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, she had the peacocks. But she's always sort of depicted as this sort of scowling figure. And that's what I have for you today about Flannery O'Connor's Why Do the Heathen Rage? A Behind the Scenes Look at a Work in Progress by Jessica Hooten Wilson.

Peter Biello: Orlando, thank you so much for bringing some Flannery O'Connor back into my life.

Orlando Montoya: It's been fun. Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand-new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at GPB.org/NarrativeEdge.

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the daily GPB News podcast Georgia Today for a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts.

When celebrated American novelist and short story writer Flannery O’Connor died at the age of 39 in 1964, she left behind an unfinished third novel titled Why Do the Heathen Rage? Scholarly experts uncovered and studied the material, deeming it unpublishable. It stayed that way for 40 years. Until now.

Join Peter and Orlando as they explore, along with author Jessica Hooten Wilson, the lessons and the what-might-have-beens of Why Do the Heathen Rage?