Section Branding

Header Content

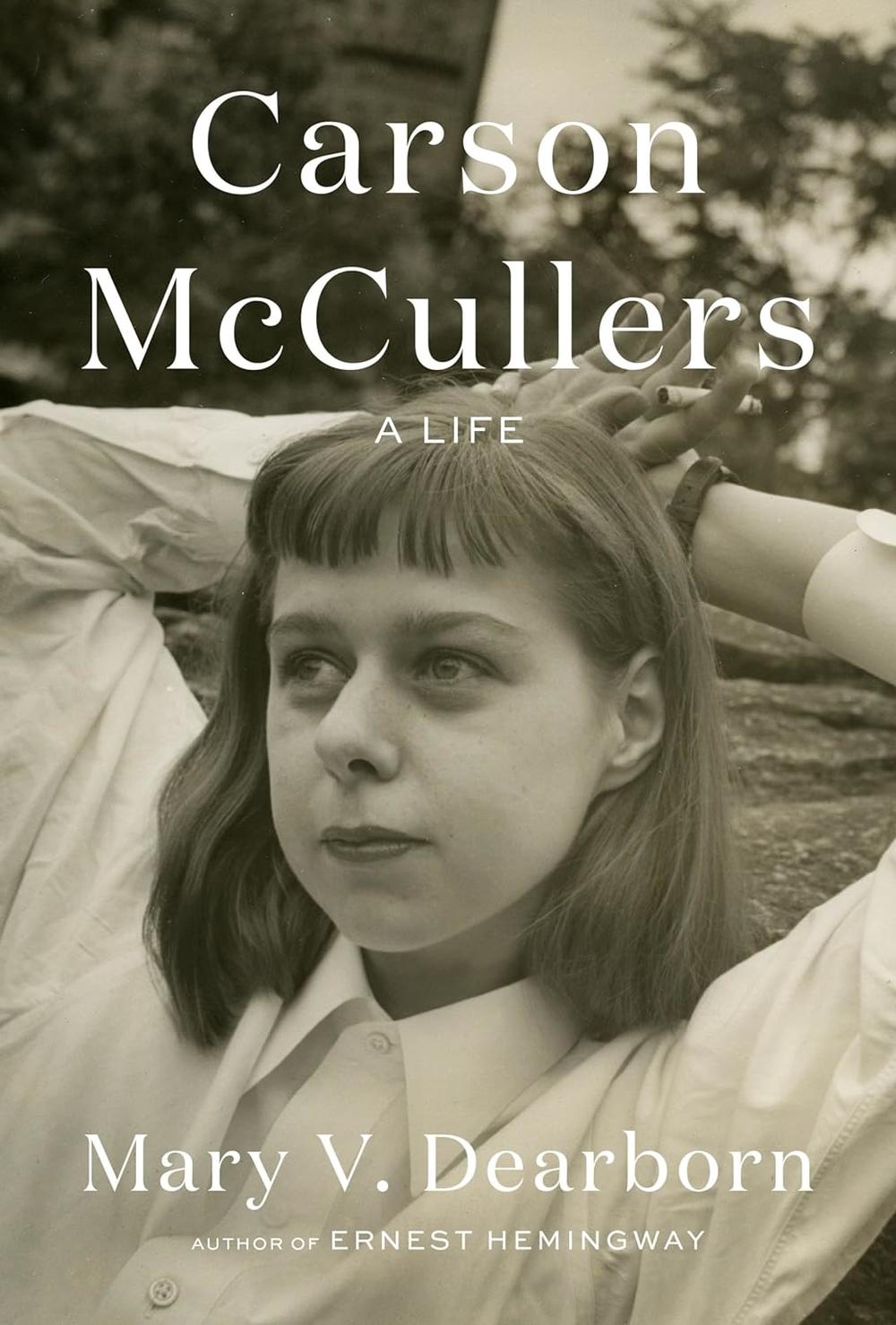

Carson McCullers: A Life by Mary V. Dearborn

Primary Content

In this episode, Orlando and Peter explore the life and legacy of celebrated Southern writer Carson McCullers. Drawing from the new biography "Carson McCullers: A Life" by Mary Dearborn, they discuss McCullers' journey from Columbus, Georgia, to literary fame in New York City, her groundbreaking works like "The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter," and delve into McCullers' personal challenges, including health issues, struggles with alcohol, and her complicated relationships, as well as her bold approach to race and gender in the mid-20th century. With insights from Dearborn's book, this episode offers a compelling glimpse into the life of a groundbreaking author whose influence on Southern literature remains profound.

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode.

Orlando Montoya: And in the 1930s that would not have been socially acceptable?

Peter Biello: Certainly not.

Mary Dearborn: Knew that she had to get out of Columbus, Georgia, and she wanted to go to New York, she wanted to go where she could be a writer, or, more accurately, where she could be among other misfits.

Peter Biello: So they display them in bookstores, and she just has this — this haunting expression in her author photo that, publishers like to put on the cover of these books.

Orlando Montoya: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia connections, hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB radio. I'm Orlando Montoya.

Peter Biello: And I'm Peter Biello. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings, and the insights behind the stories — mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge.

Orlando Montoya: All right, Peter, it's good to be here with you in the studio again.

Peter Biello: Always good to talk about books with you, Orlando.

Orlando Montoya: And we're talking about what book this week?

Peter Biello: We're going to talk about the new biography of Carson McCullers. This is a podcast about books with Georgia connections and Carson McCullers was born Lula Carson Smith in Columbus, Ga. Columbus State University has a Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians, so her Georgia roots are firm.

Orlando Montoya: So Carson McCullers. The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, correct?

Peter Biello: That's right. She wrote that book when she was, in her early 20s, published it when she was 23. This was in 1940, and she just became a young literary superstar. And she went on to write other popular novels as well, such as Member of the Wedding and Clock Without Hands. She also wrote short stories and plays.

Orlando Montoya: Now, I'm not familiar with the work, and I guess, many of our listeners might not be as well. So before we get too far, is this something that people are going to be interested in, even if they've never heard of Carson McCullers?

Peter Biello: I certainly think so. You can read this biography. It's by Mary Dearborn. It's called Carson McCullers: A Life. You can read it as a story about a creative person who had some significant struggles with her health and died young. She was only 50 when she died. I had known just a bit about Carson McCullers before —

Orlando Montoya: Maybe just the name.

Peter Biello: Just the name. Yeah. You know, and sometimes in bookstores, especially when, you know, a few years ago, Oprah selected one of her books, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, as as her selection. And you know what happens to Oprah books, right? They just they just become incredibly popular. So they display them in bookstores, and she just has this — this haunting expression in her author photo that, publishers like to put on the cover of these books. And so, yeah, she was a known entity, but I didn't know what exactly it was about her that was so special. And Mary Dearborn spells that out in her biography.

Orlando Montoya: Mary Dearborn has written biographies of people like Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, Norman Mailer, Peggy Guggenheim. Why Carson McCullers?

Peter Biello: She told me that she likes to write about notable women after spending time writing about men. And she had had her eye on Carson McCullers as a subject for quite some time. But Columbia State University recently made some material available that made writing a biography really exciting to her. So that material: Later in her life, Carson McCullers started recording therapy sessions with her therapist, whose name was Mary Mercer. Mary Mercer later became Carson's romantic partner. They made transcripts out of these audio recordings, and Mary Mercer lived for a long time. She died about a decade ago, and after she died, those transcripts were turned over. And now Mary Dearborn, as a biographer, gets to listen in on some of these therapy sessions between Carson McCullers and Mary Mercer.

Mary Dearborn: He went over a lot of her past and a lot of what worried her in her present and about her writing, but it was really just the opportunity to look in the head of this incredible, imaginative writer and just — I can't point to anything specific I saw there about what she created, but it was just amazing to see how her mind worked. And it wasn't so different from you or me, I wouldn't think.

Orlando Montoya: So let's start in Columbus. What was her early life like there, and how many years was she there?

Peter Biello: She was there throughout her childhood, but she, as we'll talk about, got the heck out as soon as she could. She went back and forth between the other places she went to. But she — she didn't really have a permanent presence in Columbus after she became an adult. But she had an ordinary childhood there. You know, her parents, they — aside from partying and drinking a lot, you know, they weren't inflicting any, like, massive trauma on her that you sometimes read about in biographies of creative types. They supported her efforts to learn how to play the piano. And she really did pursue that with some — some great effort. Almost had a career in music. One of the pieces in her early life that would resonate throughout the rest of her life is that she and her piano teacher seemed to have some romantic feelings for one another. Her piano teacher was an older woman, and Carson, withdrew from her advances but never forgot her. It seemed to be a formative experience for Carson McCullers, and one that made her feel different from everyone around her. Perhaps her first indication that she was romantically and sexually interested in women.

Orlando Montoya: And of the 1930s, that would not have been socially acceptable.

Peter Biello: Certainly not. So she felt like an outsider. And when she started writing, she wrote a lot about misfits and outcasts, people who didn't feel like they had a place in society.

Mary Dearborn: She liked to dress as a boy. She eventually took the name Carson. You know, it is androgynous, and she knew that she had to get out of Columbus, Ga., and she wanted to go to New York she wanted to go where she could be a writer, or, more accurately, where she could be among other misfits, which I think is how she saw it, kind of rightly.

Peter Biello: So she did go to New York. She spent a lot of time in New York City. There was this place called Seven Middagh, which is basically like a giant apartment building where a lot of the famous writers of the day were kind of clustered and working together and partying together.

Orlando Montoya: Seven, what?

Peter Biello: Seven Middagh? M-I-D-D-A-G-H

Orlando Montoya: Okay.

Peter Biello: And. Yeah. W. H. Auden, the poet, was there. She also became friends with people like, Tennessee Williams and Richard Wright and Truman Capote. And as Mary Dearborn writes in this biography, she kind of struck me as a, either you love her or you hate her kind of person. Like, she was very intense. She wanted to fall in love quickly. She wanted to be connected to the people around her on a very intimate basis. Eudora Welty was not a big fan of her. Same with Katherine Anne Porter. Both of those two, actually, at — at a conference they were all together at kind of, you know, would make snippy comments about her, gossiped about — about Carson and how weird she was. Carson, by the way, loved Katherine Anne Porter, but, uh, it was unrequited. Another thing we're going to talk about shortly. But she did find her community when she left, Columbus. And she did write, though she did take her time with writing her novels, in part, it seemed to me, because she was very busy socializing and also drinking heavily.

Orlando Montoya: Drinking heavily; that, uh — kind of a writerly thing in the — in that era.

Peter Biello: Yeah, yeah, for sure. And for her, for her husband. Yeah. It was a big part of their life. Her parents drank a lot, her sister drank a lot. And Reeve McCullers, her husband, you know, they really loved each other. He was gay, and she was interested in women. He was a big drinker. Their marriage was problematic. Loving at times, but problematic at times as well. The quantity of alcohol that they drank, as described in this biography is just enormous. I will say there — some argue that there was a reason for that. You know, Mary Dearborn pointed out that Carson was sick for most of her life. I mean.

Orlando Montoya: Physically, mentally?

Peter Biello: Physically sick, physically sick. She, you know, I guess back in those days, I didn't know this until I read this biography. If you get strep throat, it could turn into rheumatic fever, which could cause problems down the line, like strokes. And that's what happened to Carson McCullers. She had two strokes before she was 30. And her health kind of deteriorated from those strokes over time so that when she was close to the end of her life in the — in the '60s, you know, her left side was basically not working. She almost had to have her leg amputated. And that may have happened had she lived long enough. So, some argued that, you know, yeah, she drank a lot. Who knows how much that contributed to it. But she was also in a lot of pain. Perhaps that was why whenever doctors asked her to cut back on her drinking or stop her drinking, she didn't.

Mary Dearborn: Unfortunately, the people around her didn't say, "Carson, you know you have to — you're drinking too much." You have to stop starting with her family, who were all heavy drinkers, except maybe her brother. But her sister, who she was very close to, was in AA. Reaves was intermittently in AA, but nobody said to her, I don't think anyone said, "Carson, come to a meeting with me." You know, Carson, she was a genius and you didn't want to mess with that.

Peter Biello: So when we spoke, I asked Mary Dearborn about this, and she said, it's, you know, it's hard to tell how much was lost. You know, what could have been? How much more could Carson McCullers have produced had she not been beset by not just health problems, but — but alcohol.

Orlando Montoya: So was she a happy person? I mean, you read these biographies, sometimes — artists just terribly depressed. It sounds like, you know, they're living miserable lives when, in fact, they might be having a gay old time.

Peter Biello: Yeah, well, I wouldn't say that she was miserable. She she at one point described her own life in retrospect as the sad, happy life of Carson McCullers. That line, of course, ended up being the headline for — for a lot of news organizations reporting on this new biography. But I wouldn't say she's super depressed. She might have been inebriated a lot of the time, maybe sick, maybe worried about things as — as most of us are. You might say, though, that for her, her constant state was being in love. She was always falling in love with someone.

Mary Dearborn: She fell in love with a lot of women who weren't in a position to have an affair with her or whatever, be romantic with her. There was a ballet dancer, I mean, there — they sort of ran the gamut, but she was never very successful. You know, though she talked a big game, like how much she loved love, love so and so. But it was I would not say, though, that she was at all tormented by it. I think that's independent of sexual orientation. She just wasn't ever successful in terms of romance. So how can you say that about somebody who was loved as much as Reeves loved her? It was very curious, an interesting romantic picture.

Orlando Montoya: And there was no indication that she attempted suicide at all, ever?

Peter Biello: She does make one attempt in 1948. And then later, Reeves tries to convince them both to die by suicide together. She, of course, does not go through with this, but Reeves does die by suicide in 1953, and that really messed with her in a lot of ways. I mean, obviously, your husband dies. They, of course, always went through, you know, highs and lows in their relationship. And he died at a particularly low point. And I mention that now because, you know, she started to work through some of her feelings about her relationship with her late husband in the form of a play that wasn't really well received. So this might be, I guess you could say, a low point in her career. So she worked really hard on that play and it didn't go very well. And then, her career kind of leveled out a little bit towards the end of her life when she, she published her last novel, Clock Without Hands. It got mixed reception from critics over time, and it was her attempt to talk about race in the South. She was a Southern writer, after all, and she felt she had a point of view on the changing South, and she thought that point of view was worth sharing.

Mary Dearborn: It's not the best of her novels. It's quite good but it's, for various reasons — mostly her health — her writing was falling off a little. Not everyone agrees with that, I should say, but it's a very curious approach to race. There's a character in there — I just like this — who's Black and has blue eyes, and an antihero who she clearly loved creating is a judge who had been a member of Congress and wants to roll back time to the days of slavery, and his — his specific plan is to reintroduce Confederate currency. And, you know, he's an awful person, and the blue-eyed Black guy is related to him. And it's about the old selves meeting new realities. In a way, a brave thing for her to take on.

Peter Biello: I thought that was a particularly interesting aspect of this, because, you know.

Orlando Montoya: The racial aspect.

Peter Biello: Yeah. And because you and I have talked on this podcast about Flannery O'Connor, right, who's just a few years younger than Carson McCullers, was a white Southern woman. And O'Connor kind of struggled, it seemed, with writing about race and racial differences, whereas McCullers — not saying she got it right all the time, but she struggled, it seemed less or was a little more successful in getting the message out. That's not to say she wasn't struggling or the message was completely clear, but this novel, A Clock Without Hands, was something that she had wanted to write for years. She'd been thinking about a lot, and then when she started it, it took her years to write. She's writing during the tumult of the 1950s and '60s. So I guess that's why Dearborn calls her brave. Because then, as now, race is a difficult thing to write about in an intelligent way.

Orlando Montoya: And how old would she have been at this time? So ,1950s.

Peter Biello: She was 50 when she died in 1967. So close to late 40s, I guess, when she was writing it

Orlando Montoya: Died young.

Peter Biello: She died very young. Yeah. She was very ill by the end of her life. In the book, Mary Dearborn describes how her friends would see her and say, oh, no, she — she looks terrible.

Orlando Montoya: Was it alcohol?

Peter Biello: It was the drinking did not help the symptoms having to do with the stroke and the paralysis that she was experiencing on the left side of her body. Like, by that — by that time, she couldn't physically write anymore. She had to use, someone she had to dictate to someone. And it was a frustrating experience.

Orlando Montoya: So what gives this book the narrative edge?

Peter Biello: I think this book has the narrative edge because I read it without having read any of Carson McCullers' work. And it left me inspired to read some. I went back and I read some of her short stories afterwards, and I said, well, okay. I could see why someone would write — write a biography about this writer. She's tremendously talented. And I think Dearborn really brought Carson McCullers and Reeve McCullers to life. Their relationship was pretty visceral on the page. You know, they — they — she shared letters between Carson and Reeves. Reeves was very — Reeves provided what Carson needed, which is like constant declarations of love. She needed that. And Reeves was there for it. He meant it sincerely. And because they had such a hard time, you know, they married, they divorced, and they married again. I felt for them. They were, they, you know, for for all the success that she had, I think the problems in her life left her and Reeves unable to fully enjoy all that success with the, you know, the health problems. The alcohol problems. I think Mary Dearborn handles all this material well. She crafts an interesting life story out of it. And I think next time I'm in Columbus, I'd like to check out some of the sites like her — her childhood home, for example.

Orlando Montoya: And now I know something about The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. I thought it was a Reba McEntire song for quite a long time.

Peter Biello: It makes the I'm sure it makes these, you know, top 100 books of the century lists. And every now you know, and then you see it and you're like, oh, yeah, someday I should read this whole list. Maybe you'll start with that one.

Orlando Montoya: That's Carson McCullers: A Life by Mary Dearborn. Peter, thanks for telling me about it.

Peter Biello: Happy to. This was fun.

Orlando Montoya: Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand-new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at GPB.org/NarrativeEdge.

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the daily GPB News podcast Georgia Today for a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts.