Section Branding

Header Content

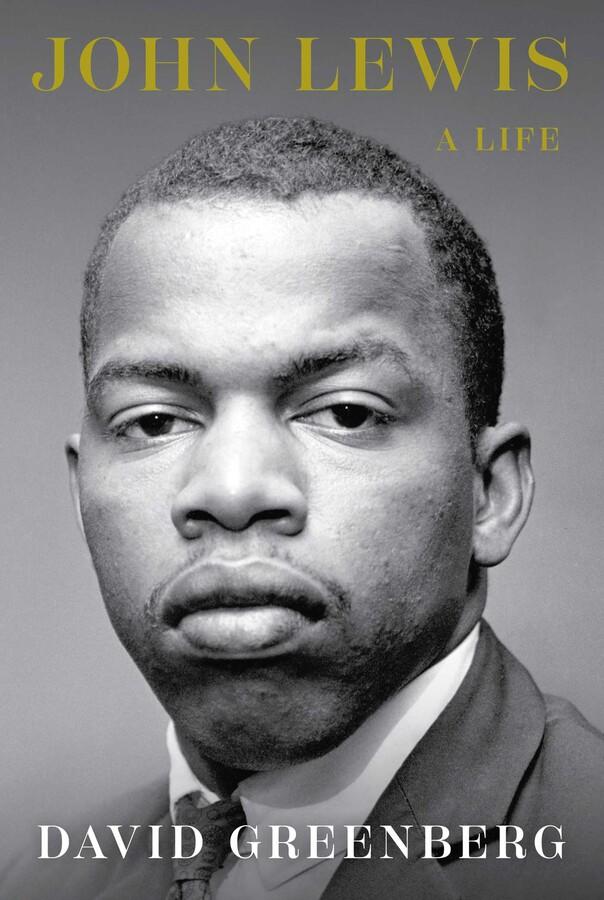

'John Lewis: A Life' By David Greenberg

Primary Content

In this episode, Peter and Orlando explore the comprehensive, authoritative biography of civil rights icon John Lewis, “The Conscience of the Congress.” The 700-page volume draws on interviews with Lewis and approximately 275 others who knew him at various stages of his life and never-before-used FBI files and documents.

Orlando Montoya: Coming up in this episode.

Peter Biello: And I imagine this is all well documented in the book. Right. Lots of drama in this section of the book.

David Greenberg: He wasn't the type you would necessarily mark for leadership. Yeah, he came from a rural Alabama background. He spoke with a thick, rural accent and a bit of a stammer.

Orlando Montoya: And I'm sure there are experts on the civil rights movement who know a lot, and they will learn a lot here, too.

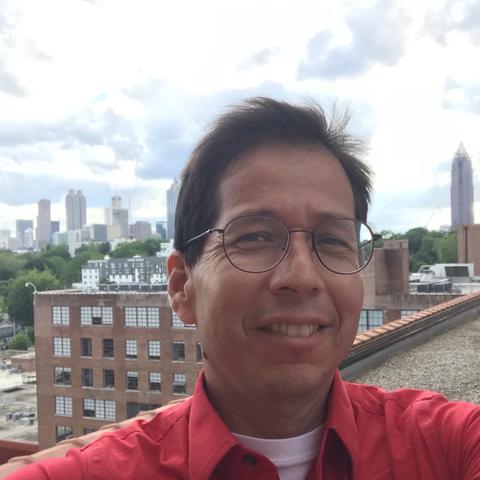

Peter Biello: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia connections hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB Radio. I'm Peter Biello.

Orlando Montoya: And I'm Orlando Montoya. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings and the insights behind their stories, mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge.

Peter Biello: All right, Orlando. Time to talk about books. And I understand you've got a big one for me this time.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, this one was 700 pages. Okay. 700 pages. John Lewis: A Life by David Greenberg. A very long but very gripping tale in parts. A lot of fascinating stories that I didn't know about, the man behind the icon.

Peter Biello: Okay. So long book we mentioned. We always make an effort in this podcast to read the entire book.

Orlando Montoya: I mean, that's what I do. If you don't read the entire book, how can you talk about it?

Peter Biello: So you — but you've got other job duties as well. So, I mean, just curious: How do you manage to squeeze a 700-page book into your routine here?

Orlando Montoya: Well, it was an audio book, so I experienced it as an audio book. It was 24 hours as an audio book.

Peter Biello: Did the author read his own work?

Orlando Montoya: No, no, no. It was very well read. But, you know, you take it in the commute, you take it doing chores, you take it, taking a shower. You take it while resting. You take it before bed. And 24 hours is perfectly manageable in that situation.

Peter Biello: Okay, so what's your best pitch as to why I should invest myself in a book of this length?

Orlando Montoya: Well, it's all about what you don't know. What you don't know. And I don't know what you know about John Lewis. And I'm sure there are experts on the civil rights movement who know a lot and they will learn a lot here, too. So, you know, I'm from a much lower level of knowledge, I have to say. I've only been in Atlanta three years. I know you've been in Atlanta for two years.

Peter Biello: Mm-hm.

Orlando Montoya: And so I sort of organized this today into sort of the five things that I didn't know about John Lewis.

Peter Biello: I like that.

Orlando Montoya: Can we do it that way?

Peter Biello: I would love to.

Orlando Montoya: Breaking format a little bit.

Peter Biello: Yeah. I don't know a whole lot about John Lewis either, except for the broad strokes. And living in Atlanta, you just sort of absorb it by osmosis, kind of. But yeah, I'd love to know the details. Okay. So tell us a little bit about how he emerged as a leader. What defined him as a leader?

Orlando Montoya: Well, the first thing that I found surprising was that he was an unlikely leader. When you look at this guy, when you hear this guy, you might ask yourself, how did he rise from his origins to become one of the prominent figures in the 20th century? And I'll introduce the author, David Greenberg, at this point.

David Greenberg: He wasn't the type you would necessarily mark for leadership. Yeah, he came from a rural Alabama background. He spoke with a thick, rural accent and a bit of a stammer. When he got to the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, not — itself not a particularly big place, even there, he seemed kind of a bit of an outsider: pure hick, his friend Bernard Lafayette said. And he was shy. He lacked a certain amount of self-confidence. And yet, within a short time, certain natural leadership qualities emerged in him.

Orlando Montoya: And Greenberg doesn't even go into a lot of it there. This guy was dirt poor. We're talking on a farm in rural Alabama near Troy. And not only that, but, you know, as he sort of was young and even emerging throughout his life, he had frumpy dress. He was hard to understand and he was a very serious man, very preacherly, you know. And when all the young people, they don't want to be around this preacherly, moralistic, very serious guy. So, you know, in his early years, there were certainly other more debonair and suave leaders.

Peter Biello: Yeah. And I'm curious about how he did develop that confidence.

Orlando Montoya: It was the crucible of Nashville.

Peter Biello: The crucible of Nashville?

Orlando Montoya: I'm going to call it the crucible of Nashville. I'm making up that term.

Peter Biello: OK!

Orlando Montoya: I've been just making up that term. That's where he started with the lunch counter sit-ins, with the theater protests≤ and the organizing details that you need to lead such a movement. I'm talking about printing fliers, calling meetings, asking people to show up for the meetings, asking people to show up again. Training people and training people again because, you know, these people were being beaten, they were being yelled at and arrested. And he never responded with this hatred, with violence. He was always calm. He was always the first to arrive, the last to leave. Always tireless. And he never let the hatred infect him. And so I think that the second thing that really surprised me about John Lewis' life was his lifelong, non-negotiable belief in nonviolence.

John Lewis: The first time I got arrested was February 1960. I felt so free.

Interviewer: Really?

John Lewis: I felt liberated. I felt like I crossed over because I have been told by my parents and others "don't get in trouble." But it was good trouble. It was necessary trouble.

Peter Biello: Good trouble. That's the classic phrase.

Orlando Montoya: That's his signature phrase. People saw this commitment. They saw this sacrifice — being bloodied, being almost killed on the Selma bridge. He was called a saint. And people want to emulate that. That's how he became a leader. When you ask the question, "how did he become a leader?" That's how. You know, why do we have saints in the Catholic Church? You're a former Catholic. You know. You have saints because there's people to look up to. And so it was that unwavering commitment that was important when he — especially when the movement started to fracture

Peter Biello: Fracture? What are you — are you talking about the "Black Power" and more radical militant expressions of the movement?

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, exactly. Think about this: After the Freedom Rides, after Bloody Sunday, after the March on Washington, after his stunning leadership of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he was forced out as SNCC in this very hurtful ouster because at that point the young people were shifting to a more, like you said, more radical, more militant expressions of of civil rights. And this ouster in 1966 really hurt him for the rest of his life. It was a turning point. And he was only age 26.

David Greenberg: It's a low moment for him. The civil rights movement and in particular SNCC, the organization he led, has moved away from the ideals of nonviolence and interracial cooperation toward a more Black separatist philosophy. Lewis leaves Atlanta, spends a sort of unhappy year in New York City, then gets back into politics working for Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 campaign. But that spring has to withstand and suffer the assassinations of both Martin Luther King, his great mentor and idol, and of Robert Kennedy, who he sort of had seen as claiming King's mantle.

Peter Biello: So how did he handle this low point?

Orlando Montoya: Well, I think a lot of it had to do with his meeting his future wife, Lillian Miles. And Lillian is a force throughout this entire book. She helped him, really defended him. She was, in some way, his organizer. It was also his fulfilling work in voter education. He landed several jobs, you know, both in private and in public work, doing voter education.

Peter Biello: So did he ever forgive the people who had ousted him?

Orlando Montoya: Eventually, yes,

Peter Biello: Eventually.

Orlando Montoya: Stokely Carmichael was the one in particular, Stokely Carmichael and his allies who took over SNCC. He didn't speak ill of them after that immediately happened. He sort of thought that the cause was more important than this petty infighting. And so he sort of kept his calm. You know, he didn't let the event boil over him at the moment, and he just kept it to itself and he moved on. SNCC eventually died in the early '70s. Later in his career, his sort of feelings about all that cooled.

Peter Biello: And I imagine this is all well-documented in the book.

Orlando Montoya: Right.

Peter Biello: Lots of drama in this section of the book?

Orlando Montoya: Yes, lots of drama.

Orlando Montoya: And that's the third thing that I didn't know about John Lewis. And that's his his clashes with with certain people, specifically Julian Bond and Jimmy Carter.

Peter Biello: Hmm!

Orlando Montoya: Julian Bond was his best friend. They were very tight. They hung out together. They were soldiers in the movement. Their wives and kids hung out together. They grew up, you know, in SNCC and Bond later went on to form the Southern Poverty Law Center. Bond went on to a career in the state House and Senate. But it was that 1986 when they both decided to run for Congress. First, they started out kind of civil in this race, and then things got nasty.

Peter Biello: Because this is a primary, right?

Orlando Montoya: Yes. So the primary was going to win the general election.

Peter Biello: Got it. Okay. So what was nasty about this?

Orlando Montoya: Well, the headline in that race, in that nastiness, was the cocaine.

Peter Biello: Oh no. So whose cocaine?

Orlando Montoya: Julian Bond's.

Peter Biello: So allegedly Julian Bond's, or definitely Julian.

Orlando Montoya: Allegedly, Julian. And I want to definitely say that this was like rumors and sort of people had sort of heard that Julian Bond was doing cocaine and Lewis stayed away from it. Lewis stayed away from it until the very end. And — .

Peter Biello: Directly, or through surrogates?

Orlando Montoya: Directly.

Peter Biello: Wow.

Orlando Montoya: Directly.

Peter Biello: Would never have guessed, given his reputation.

Orlando Montoya: Well, I think there also was a lot of difference between them in style and substance as well, because Bond was from a well-heeled Black family. His father was a college president. Bond's childhood home was —was filled with people like W.E.B. Dubois and Paul Robeson. He was well-spoken. He had nice clothes. He drove a fancy car. He was Northern-educated. And on the other hand, you had Lewis, who is this dowdy son of sharecroppers, Southern-educated, very religious. And, you know, there were just two different appeals. Lewis also appealed to white people in a diverse Atlanta district. Lewis always believed in multiracial coalitions, LGBTQ people. He reached out to Jewish people he reached out to, and then that nasty campaign, there were whispers of, you know, "Lewis is not Black enough," you know? And — and, in fact, Bond made an unfortunate comment about Lewis being more concerned with the citizens north of I-20. And we know that that means white. So in this very close, close race, it turned nasty at the end.

Peter Biello: So what about the Jimmy Carter fight? What was it about their relationship that just didn't jell?

Orlando Montoya: So the Lewis clash with Jimmy Carter wasn't as dramatic or painful or hurtful as the clash with Bond. But I'll introduce this clip by Greenberg, who'll answer the question by just saying that Lewis did work for Carter in the last few years of Carter's administration for an agency that was aimed at helping the poor by overseeing some volunteer-based organizations.

David Greenberg: By the end of Carter's presidency, when Ted Kennedy, who was a great friend of John Lewis', decided to challenge Carter for the Democratic nomination, Lewis was quite torn. You know, his — his heart really was with Ted Kennedy. But he also was enough of a loyal man and he wasn't going to publicly betray Carter. So he ended up resigning a little early from the Carter administration, sort of sitting it out. He later then tussled with Carter in Atlanta over fights over building a parkway out to the Jimmy Carter Library, where John Lewis fought with the preservationists, the environmentalists who wanted to protect a lot of the green space that was going to be destroyed by that highway.

Orlando Montoya: And so you probably drive on that highway from time to time.

Peter Biello: Yeah. For folks who aren't fully aware, the John Lewis Freedom Parkway basically wraps around the Carter Center in Atlanta.

Orlando Montoya: It's now called the John Lewis Freedom Parkway, but it was originally the presidential parkway. And it was originally and I don't know if you know this history, but it was originally planned out to go much further out and destroy a lot of neighborhoods and connect with other highways. It was part of a big, you know, mid-20th century plan to just pave over everything and build highways.

Peter Biello: But it basically stops at a giant park now.

Orlando Montoya: Now it just stops at a giant park.

Peter Biello: Which is a very pretty park. I've biked there. Have you?

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, I did so the other day. But, you know, he and others stopped this highway. They fought successfully to stop it. And that was one of the causes that sort of endeared him to voters in some of the wealthier, whiter neighborhoods, because those were the neighborhoods that it was going to go through. But again, he thought it was just something that was wrong. And so he stood against it.

Peter Biello: So interesting that the highway gets his name right outside the Carter library.

Orlando Montoya: Certainly ironic. And it's called the John Lewis Freedom Parkway when he fought to stop it. He certainly did not clash with Carter, you know, and like I said, in the way that he did with Bond. He admired the Georgia governor who took Georgia out of its segregationist past. But there was, again, that primary fight and the highway fight.

Peter Biello: All right. So you counted three things that surprised you. You promised five. You've got two more, I believe.

Orlando Montoya: Yes, I've — fourth thing! Fourth thing that I did not know about John Lewis is just how much of a rock star he was? Did you know how much of a rock star this guy was?

Peter Biello: I get the sense toward the end of his life that, yeah, he was just kind of in an institution, really.

Orlando Montoya: This guy was — he was a sought-after speaker. So he could be deployed to congressional districts around the country to raise lots and lots of money. But then just ordinary people on the street, they would see him and want to go up to him and they would cry when they met him. And, you know, just the other weekend I was talking about this with a friend that I'm going to talk about this subject. And he said, "I met — I met John Lewis" in the ATL Airport, the Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, and he was on the shoeshine. And, you know, and he said hello and took my picture and all that. You know, he loved signing autographs sometimes to the consternation of his staff, who always wanted him to move along. But he was such a rock star. Did you know about the Stephen Colbert crowdsurfing video?

Peter Biello: No, I did not know this one. He crowdsurfed?

Orlando Montoya: He crowdsurfed! the man was 70-something years old and he goes on Stephen Colbert and he goes out into the crowd and gets crowdsurfed. Well, I had to look up the video.

Peter Biello: Like he jumped off a stage into a crowd of people and they picked him up.

Orlando Montoya: It was more like leaning into the crowd. And then the crowd took him along. But yeah, it was — that's how much. It went viral. And of course, you know, that was one thing I didn't know: just how much of a rock star. And the fifth and final thing that I'll mention is I did not know that in Congress, he actually was not much of a policy wonk. I mean, for all of his rock star status, the book sort of points out that legislation — getting legislation passed was not his strong suit in Congress.

Peter Biello: Who is good at that right now? I'd love to know.

Orlando Montoya: Well, not many people, I guess.

Peter Biello: But in his defense, I suppose I could say that.

Orlando Montoya: You can say that about anybody. Yeah.

Peter Biello: Anything that's not very obviously bipartisan is — is going to get stalled at some level.

Orlando Montoya: Now, he was not, you know, let's count the votes. Let's wrangle politics. Let's research the policies. He was more like the moral force. He was — his word had tremendous influence. And he was called the conscience of the Congress. That's another phrase that that often comes up about him. He was the conscience of the Congress. But the details: legislating, not much his thing. I think he much more liked being, you know, this sort of rock star person.

David Greenberg: He learned to be a good congressman and sort of bring home the bacon for his district, helping Atlanta with airport funding and highway funding that helped make it the big, dynamic, entrepreneurial city that it was becoming. At other times, he accepted compromises when he realized that in a divided country with divided government where the Republicans had a lot of power, you had to accept a bill that maybe was not quite all you wanted it to be. So some people might see opportunism or too much of a willingness to fall in line with the Democratic Party. But John Lewis saw this as getting stuff done.

Orlando Montoya: He got stuff — I should say he got stuff done for his district by bringing home the bacon. But as far as big legislative accomplishments that affect people nationally, I think the biggest thing that the book pointed out was the law that created the National African-American Museum. That was his biggest legislative accomplishment. It took 15 years. There were many hurdles for him to overcome to get that done. But that was sort of his biggest accomplishment as a lawmaker, according to the book.

Peter Biello: So he died a few years ago. How does the author write about his death?

Orlando Montoya: Well, it's very sad. And I have to say, I started to cry at the end. And who wouldn't? When you hear about, you know, the man's life and the people that he loved and the things that he cared about. And the end was pancreatic cancer. And it came rather suddenly, as pancreatic cancer does. My own mother died of pancreatic cancer. And it came during the height of COVID. And for this man to be so active, to always be this energetic person and just to see him die like that, it was very sad.

Peter Biello: Sorry about your mom, by the way. So what gives this book the narrative edge?

Orlando Montoya: It's a major biography of a major figure in U.S. history. Let's just start there, okay. And I think it's written from a perspective of bringing you to the scene. It puts you in the minds of the people who were there at the time, what they were thinking. You know, we see and we hear about Bloody Sunday and the Freedom Rides. But what actually happened, like the moment to moment, day to day things, the logistics of it, how things could have turned out differently — it's very surprising. And it answered a lot of questions for me. It was long, but it was worth it. I mean, an especially if you have a character like this one. I mean, when he was asked about his greatest accomplishment — and these clips, by the way, that I've been playing, come from a gpb interview from, I believe, 2006. But when he was asked about his greatest accomplishment. Here's what he had to say.

John Lewis: I find a way to get in the way. I think you just have to get in the way. You don't have to be popular. Just when you see something that is not right, speak up. When you see something that is so wrong and so evil and so vicious; when someone has been put down because of their race, their color, their religion and nationality or whatever, you have to do something. You cannot afford to be silent. You have to do something. You have to make some noise. I said to young people today, said "We are too quiet. We need to make a little noise." My generation, we were not quiet. We made a little noise.

Orlando Montoya: And that's why the book is worth reading.

Peter Biello: Was so cool to hear him say he found a way to get in the way. A great way of putting it.

Orlando Montoya: That was what he saw as his life's greatest work.

Peter Biello: Well, the book is John Lewis: A Life by David Greenberg. Orlando, thank you for reading it.

Orlando Montoya: Thank you. It's been a long book. It's been a long podcast, but worth it.

Peter Biello: Well worth it.

Orlando Montoya: Definitely worth it. Thank you very much. Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode as podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at gpb.org/narrativeedge.

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the daily news podcast Georgia Today. For a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts.