Section Branding

Header Content

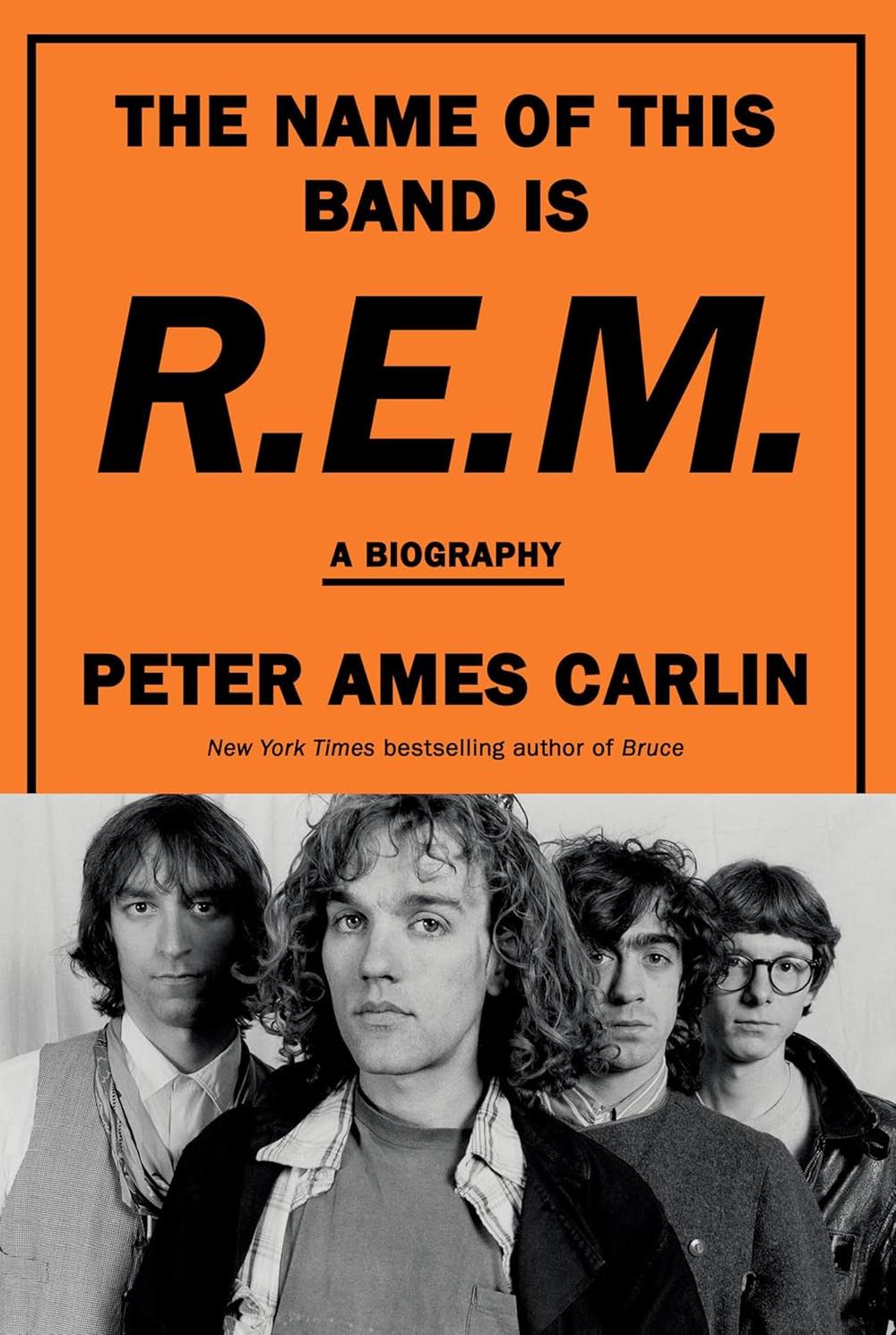

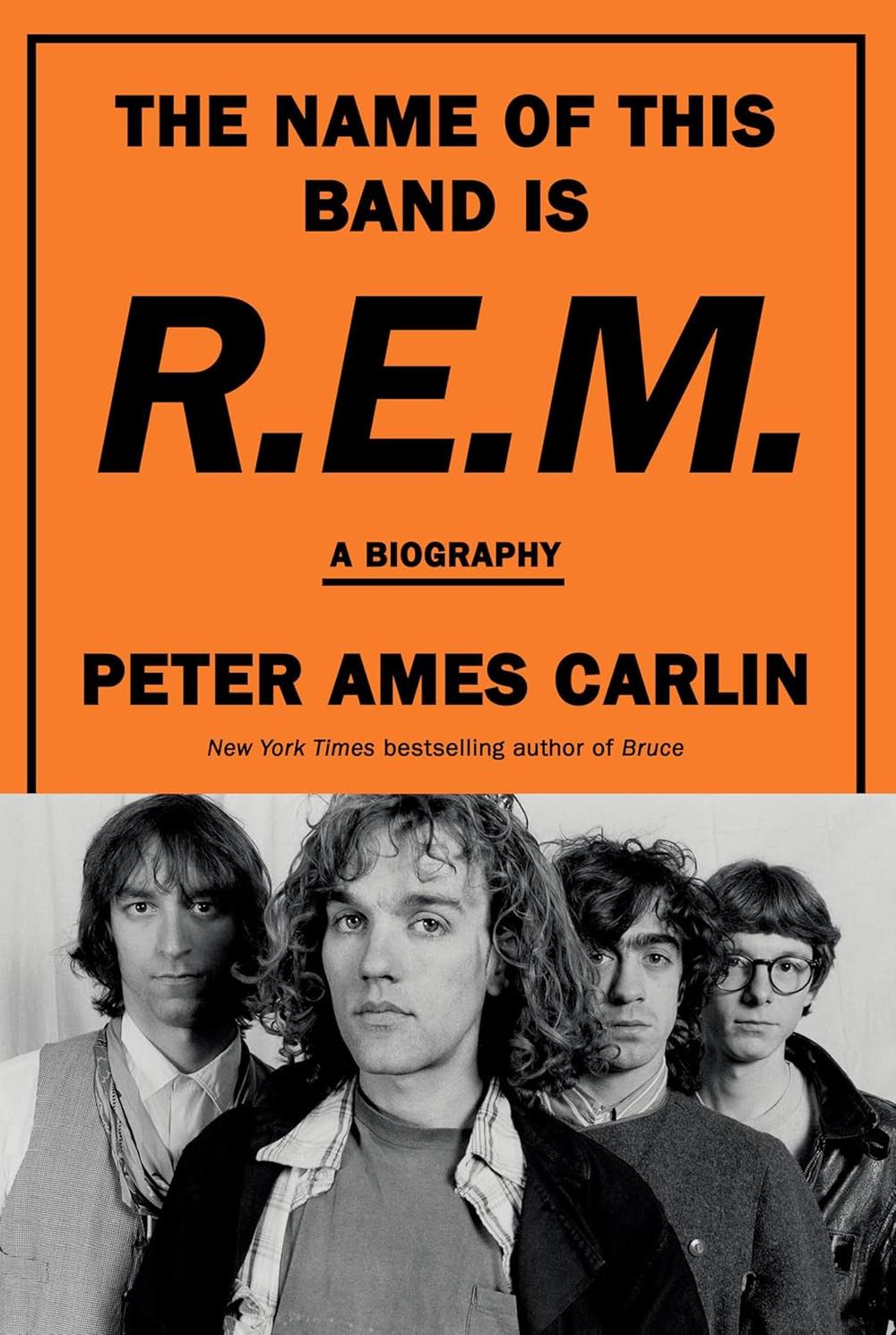

The Name of This Band Is R.E.M. by Peter Ames Carlin

Primary Content

Peter and Orlando explore this rich, intimate biography, from critically acclaimed author Peter Ames Carlin. This book looks beyond the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll to open a window into the fascinating lives of four college friends — Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Bill Berry — who stuck together at any cost, until the end.

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode.

Orlando Montoya: So that's why I picked up this book. I wanted to understand why they were such a cultural touchstone.

Peter Biello: First of all, it sounds incredibly difficult to work with these guys.

Peter Ames Carlin: And they managed to make the mainstream bend in their direction rather than the other way around.

Peter Biello: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia connections hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB Radio. I'm Peter Biello.

Orlando Montoya: And I'm Orlando Montoya. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings and the insights behind their stories mixedd with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge. All right Peter, I'm going to start with a hypothetical question.

Peter Biello: All right, let's hear it.

Orlando Montoya: So let's assume this podcast gets way big. We're talking huge, millions of dollars, like we are rolling in it. And it's made us completely rich and famous.

Peter Biello: I mean, that's what I thought going in.

Orlando Montoya: The catch is — the catch is now that we're owned by some big corporation that's giving us all this money, we can't interview who we want to interview. We have to sort of perform the way other people want us to perform. We have to sell out.

Peter Biello: Our corporate overlords will control our lives.

Orlando Montoya: Would you sell out?

Peter Biello: Hell, yeah. Everybody's got a price, man. Everyone's got a price.

Orlando Montoya: Well, the reason I'm asking is because the book that we're going to talk about today, the central premise of it, is that the members of R.E.M. are not sellouts.

Peter Biello: Okay.

Orlando Montoya: That the famous Athens alternative rockers have held true to their roots. They've held true to their alternative spirit. They've held true to themselves. And they are not a sellout. They're a great band. The book is called The Name of This Band is R.E.M. by Peter Ames Carlin.

Peter Biello: Well, first of all, I love a good music conversation with you. This is not the first one.

Orlando Montoya: And especially a group from sort of my age bracket. You know, we're both of the age that we should know. R.E.M.

Peter Biello: Yeah, for sure. For sure. I — I come into this conversation knowing R.E.M. a few songs by them, and there's a guy named Michael Stipe in the band who's a big deal.

Orlando Montoya: Well, I never disliked their music, but I never liked it either. I was kind of like, I like their hits, right?

Peter Biello: Yeah.

Orlando Montoya: I know their hits. I like their hits. I can see their superstardom, but I never really understood it. So that's why I picked up this book. I wanted to understand why they were such a cultural touchstone, why they were so great.

Peter Ames Carlin: The overarching achievement of R.E.M. was their ability to confound expectations and to confound the demands of, you know, the culture and the industry and be able to say, "We don't do it that way. We do it this whole other way" and A) not only get away with it, but B) you know, transform the culture and change the way that it was done.

Orlando Montoya: Well, there's a lot to unpack there.

Peter Biello: Yeah.

Orlando Montoya: In that little bite. But from the very beginning of the book, Peter Ames Carlin argues that in many ways, R.E.M. succeeded in spite of themselves because they were so alternative and so non-mainstream; their music didn't fit into any of the neat categories of the early '80s.

Peter Biello: Yeah, so we're talking early '80s through the '90s. That's when I became aware of them in the early '90s. So what I mean, he talks about them being sort of against the grain. What was the grain at the time?

Orlando Montoya: Well, this was the music of the early '80s. So what, that music is punk, right? That music is hard rock. It's new wave. It's glam rock. And back then, they kind of delighted in coming out with records that did not fit into any of those categories. There was you know, they talked about, well, they would get their records and the record stores didn't know where to put them.

MUSIC

And then, of course, there's Michael Stipe's lyrics. He kind of mumbled the lyrics. The lyrics were always kind of hard to understand, and the lyrics were kind of mysterious and oblique anyway. So from the music side, they were kind of misunderstood, right? And then they weren't understood from kind of like the hitmaking promotional habits of them.

Peter Biello: Yeah. So songs like "Losing My Religion," for example, not super easy to understand or categorize. It's a vibe. You like it, but what is this about, really?

Orlando Montoya: Well, we haven't even gotten to "Losing my Religion."

Peter Biello: Okay, we're going to get to that, I guess.

Orlando Montoya: We're starting like back in the '80s. They started in 1980, as you may know, in Athens, Ga. They were college students and college dropouts. In some cases. They're just a guys who wanted to form a band and play good music. But then they, when they started to, you know, have shows and even have a record contract, they had all these promotional habits that really worked against them.

Peter Biello: What do you mean promotional habits?

Orlando Montoya: Well, for a long time, Stipe didn't like being interviewed. As the front man, that's kind of expected. You're the one who's supposed to go out and answer the questions, But he didn't like doing that. And there's the example of their first national TV appearance on Letterman. When they go on David Letterman and the guys come out there and perform their song and then Michael Stipe goes, hides in the back, and the other the other band mates are left to answer the question.

David Letterman: Thank you, folks. Welcome back. This is R.E.M. Peter Buck. Nice job, Peter. Nice meeting you, sir. And I'm sorry. Your name again, sir. It's Mike. Nice to see you, sir.

Orlando Montoya: So Michael Stipe didn't like being interviewed, and for a long time, they refused to shoot music videos that were anything that their record company or MTV wanted. There were these music videos. Where do you remember any of them? These sort of weird ones that were kind of upside down, black and white? Brush pictures, you know, And their music. Their music label is saying, you know, give us a video that we can get on MTV. And they're saying, "no, we won't. We don't want to do it." And they didn't appear on their album covers. Michael Stipe said, I'm not lip synching to lyrics on the videos. And they, even when they got big and famous, they refused to promote some of their biggest albums by going out on tour. And this went on for a long time.

Peter Biello: Didn't last forever, obviously. First of all, it sounds incredibly difficult to work with these guys. They must have really liked their music to stay committed to people who seem so hard to work with. But when they did these things, the things that they previously refused to do, is that when they were accused of selling out, when they finally made the music videos that I ended up seeing in the '90s, for example.

Orlando Montoya: Absolutely. But the author's take on it is: What were they supposed to do? They wanted their way to become mainstream, and it did.

Peter Ames Carlin: They were going to take their sound and their art and their ideals to this broad population. And I don't think that they thought from the beginning there that they understood exactly how to do that or what that was going to look like or feel like. But they just figured they would walk down that road and see how far they got before either they hit a dead end or they just couldn't tolerate it anymore. But as it turned out, they were exceptionally gifted at being able to appeal to the mainstream without distorting their, you know, themselves and their artistry in order to appeal to the mainstream. They managed to make the mainstream bend in their direction rather than the other way around.

Peter Biello: So in other words, they hit the sweet spot. They — they could have the best of both worlds.

Orlando Montoya: According to the author.

Peter Biello: According to the author.

Orlando Montoya: I mean, there are some people who thought they did sell out. You know, and the author does get into some of that criticism. But I didn't know a lot of their music before I read this book. And what I did was as the book was going along and the author talked about a particularly important song or song that kind of sounded like it was a — represented a change or it was very important. I went and I listened to it. Right. I'm not going to tell you I listened to their entire catalog. But I listened to sort of the important songs, the important albums. And I said, "You know what? I don't think they did change." They — they remained the same sort of weird way the whole way through. And, you know, so I think that — that he was probably right in their assessment now. We'll get to some of their other more controversial points later. But I think that for the bottom line, I don't think they can be accused of selling out music-wise.

Peter Biello: Okay. Well, there must be a few other R.E.M. books out there. What makes this one different from those?

Orlando Montoya: Well, again, I haven't read all of the other R.E.M. books, but Peter Ames Carlin did. And this is how he answers that question. And I should note here that Carlin also has written books about Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, and Brian Wilson, among others.

Peter Ames Carlin: A lot of the people that I've written about have already had books written about them. But for me, the question is, is there the book that I want to read about this person or about, you know, this artist? And in this case, you know, one of the things that was interesting to me was that the books that did exist about R.E.M. — certainly the narrative biographies — had all been written by British writers. And and they're great. They're fine. I mean, and and we're focused almost specifically on the music and the music industry, which is terrific. That's a great way to write about artists like this. But I was interested in R.E.M. as not just as musicians and artists and successful pop stars, but also in what they represented and achieved in a cultural context.

Peter Biello: Okay, so what does he mean by that? Exploring, explaining R.E.M. in a cultural context?

Orlando Montoya: Well, there's a lot in the book about the political and social atmosphere of the 1980s and 1990s that relates to R.E.M.'s career. I mean, the most obvious one is Michael Stipe's sexuality. Is he bi? Is he gay? Is he queer? What are we going to call him? You know, he dresses in a non-gender-conforming way sometimes. Then there's Rock the Vote. You remember Rock the Vote?

Peter Biello: I remember the effort. Yeah.

Orlando Montoya: So, yeah, they wanted to get motor voter laws passed. And then MTV came up with this big campaign that ultimately was successful. And R.E.M. was a big part of Rock the Vote. The book also goes into a lot of placing R.E.M. within the musical cultural context of the scene around Athens, the South and the nation. There's a lot of bands in here I don't know.

Peter Biello: Okay. So does that take away from the story.

Orlando Montoya: That was the weakest aspect of the book, in my opinion. If I did have one criticism, I don't think I need an extended passage about Bill Clinton or Tipper Gore. You know, I was there. What propels this book forward for me and what kept me reading was I know where the story is going. I know that R.E.M. is going to get super huge, and I know that they're going to fall. But how are we going to get there? Will there be drama between band members? Will there be bad behavior? Yes and yes. It's a band.

Peter Biello: Can I ask: Did the band talk to the author?

Orlando Montoya: No. So actually, that was also something that I might have liked, but maybe not. I mean, the author had his own take on that subject.

Peter Ames Carlin: It's always disappointing when you set out to write about someone and they don't want to cooperate, but on the other hand, it can also — that kind of a little bit of distance can give you a different and in some ways more clear perspective on them because you're hearing from their, you know, their friends and family, you're hearing from the people they worked with. And also, you know, with a band like R.E.M. that was so successful for so long, you know, there's just so much printed material tracking the way that they feel felt about their work and their career and their lives contemporaneously from moment to moment to moment. And I could find and read and absorb all of that stuff. You know, in some ways, that becomes a more important story anyway, because that's how the audience has perceived them. And that's what's important is, you know, the creation of the work, the work itself and how the work affects the people who, you know, who hear it.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah. So that's basically his take on that.

Peter Biello: So sounds like he's sort of making hay of the situation that he has. But. Ideally, you'd want to talk to them, right? You want to get a sense of "This happened. What do you recall about when this happened?"

Orlando Montoya: Well, and then I get the sense from the book that at this point, R.E.M. are just like done with everything. They're retired, they're doing their art projects, and they don't really want to have to do anything with the band anymore.

Peter Biello: Oh yeah. Even their royalties, too. Yeah, just forget all about those.

Orlando Montoya: So, I mean, and another thing about the book that I like is that he kind of drops little hints about where things are going and where we've been to kind of remind us the story. So it really is superbly written that way. I mean, how many times in this book does he mentioned the birthday party at the former church.

Peter Biello: Really? What is that?

Orlando Montoya: That's where they all began in 1980. It was a birthday party in a former church building that had been converted into student housing off campus. And so they took it over and had a birthday party. And everything after that kind of gets weighed against that moment.

Peter Biello: The ultimate act of counterculture, having some blasphemous music in a former church.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah. So that was one thing that I liked about the work, the book, the way he wrote it. And another thing was just learning all about the hits, you know, all about those songs that I knew. "Shiny Happy People," "Stand."

Orlando Montoya: "It's the End of the World As We Know It."

Orlando Montoya: And the big one.

Peter Biello: "Losing My Religion."

Orlando Montoya: That one in the corner.

Peter Ames Carlin: The song that was their biggest hit, "Losing My Religion," is like one of the weirdest songs to ever hit the top 40, let alone, you know, the top two, which, you know, and — and to sell a million copies, which it did in 1991. Because at a time when music was so overwhelmingly electronic and synthesized and sleek, here was a song that was — not only featured a mandolin as its lead instrument, but also, you know, a lyric that was, you know, that played like a set of riddles, you know, that was almost in code because Michael was using an anachronistic Southern expression, "losing my religion" to describe these feelings of being out of — out of control and in a love affair that was, you know, overwhelming and and, and, and, you know, and frustrating and painful and and beautiful at the same time.

Peter Biello: Okay, So as the resident Yankee of this podcast, I have to admit, I didn't know "losing my religion" was a Southern expression.

Orlando Montoya: I didn't know that either.

Peter Biello: Okay. Well, if you don't know, I feel less bad about it.

Orlando Montoya: And he's talking in codes like throughout his song. He is the master of the mysterious lyric.

Peter Biello: Okay, so back to the central question of selling out. The author doesn't think they sold out. But what about you? Someone who's not a fan?

Orlando Montoya: You know, I'll go easy on them. They changed their mind. They changed their mind. When new information came to be, they changed their mind. Everybody gets to change their mind. But I will say there was a point in the book where I stopped rooting for them.

Peter Biello: Really? Okay. This sounds interesting to me.

Orlando Montoya: Well, you know, they're — they start out they're the scrappy band. They're going across the country in a van. And I mean, they're always nice people. But there comes a point in the book where they're now in five buses and they now have jets and they're now, you know, have levels of backstage passes and they now are having contracts that specify what alcohol and food is to be in the concert venue. And they're complaining about being famous. "Aw, I'm famous!" Meanwhile, they're, you know, they're hanging out with A-list celebrities in Hollywood. And that's the point where I'm kind of like, "you know what? I'm — I'm not rooting for them anymore."

Peter Biello: But isn't that the way with so many bands? Right? You know, that the success gets to their head in a way and their music changes as a result. Did you feel like the music changed when they got that way, or did they—?

Orlando Montoya: I don't think the music I don't think the music changed. I mean, from a strictly non, you know, fan point of view. I think it's the same weird as now as it as it was back then. You know, I think other critics — and he points this out in the book — other critics do find changes that some would call selling out. But me, I again, I didn't connect to it. So I kind of think it's the same weird it was before.

Peter Biello: Well, that's fascinating. Awesome story, then. Thanks so much for sharing this. The book is called The Name of This Band is R.E.M. by Peter Ames Carlin. This was great. Thanks, Orlando.

Orlando Montoya: Thank you very much. Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand-new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at gpb.org/narrativeedge.

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the daily GPB News podcast Georgia Today. For a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts

Peter and Orlando explore this rich, intimate biography, from critically acclaimed author Peter Ames Carlin. This book looks beyond the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll to open a window into the fascinating lives of four college friends — Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Bill Berry — who stuck together at any cost, until the end.