Section Branding

Header Content

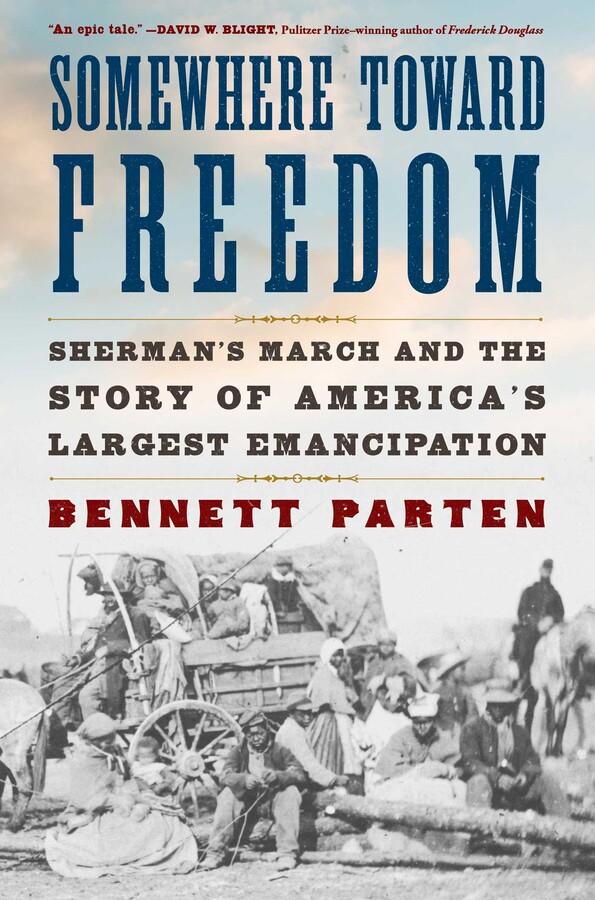

Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman's March and the Story of America's Largest Emancipation By Bennett Parten

Primary Content

A groundbreaking account of Sherman’s march to the Sea — the critical Civil War campaign that destroyed the Confederacy — told for the first time from the perspective of the tens of thousands of enslaved people who fled to the Union lines and transformed Sherman’s march into the biggest liberation event in American history.

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode.

Bennett Parten: This federal project is a really important moment early in the war that begins this transition from slavery to freedom.

Peter Biello: And the army has to decide, okay, so what do we do with these people?

Orlando Montoya: Okay, I know what they do with these people.

Peter Biello: You know what they do.

Orlando Montoya: But tell everybody.

Peter Biello: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia connections hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB Radio. I'm Peter Biello.

Orlando Montoya: And I'm Orlando Montoya. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings and the insights behind their stories mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge.

Peter Biello: All right, Orlando, I've got a book about the Civil War to tell you about.

Orlando Montoya: Ah, Civil War. There are so many books about the Civil War.

Peter Biello: I know, but why not one more?

Orlando Montoya: We've done Civil War podcasts before, but let's — let's hear about this one.

Peter Biello: Yeah, we've done the very first episode of this podcast, actually. Listeners should check it out. When you read Ilyon Woo's novel Master Slave Husband Wife, Civil War-adjacent, dealing with slavery. But we haven't done one about the war itself.

Orlando Montoya: Well, it's about time.

Peter Biello: It's about time. Yeah. This book is about actually a refugee crisis that the Civil War created. You may have heard of Gen. Sherman's march to the sea.

Orlando Montoya: The infamous march to the sea.

Peter Biello: The infamous march. Did you know it was a refugee crisis?

Orlando Montoya: Sort of, yeah. They were being followed by the emancipated enslaved people.

Peter Biello: I mean, it makes sense when you think about it, right? If you are the Union Army, right? You're liberating people as you go. And if you are a formerly enslaved person with — with not much to your name and not much protection, you're going to hang out with the people who are protecting you. So that's why they followed them along. And, you know, they kind of accumulated along the way.

Orlando Montoya: And that's what we're talking about here in this book.

Peter Biello: Yeah. The book is by Bennett Parten. And it's called Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman's March and the Story of America's Largest Emancipation.

Orlando Montoya: Who's Bennett Parten and how is he qualified to tell this story?

Peter Biello: He's very qualified. He's an assistant professor of history at Georgia Southern University. This book was his Ph.D. thesis at Yale. David Blight was his professor. You may have heard of that name; he's an incredible biographer. I had the chance to interview him when I worked in New Hampshire about his giant biography of Frederick Douglass. Bennett Parten was a pleasure to talk to. In fact, there's a video of our full conversation. We talked for about almost a half hour or so. You can find that on YouTube. We also link to it at gpb.org/news

Orlando Montoya: So let's get marchin'. March to the sea.

Peter Biello: Let's get marching. So we know Gen. Sherman marched the Union Army from Atlanta to Savannah in the fall of 1864 toward the end of the Civil War. This is the famous march to the sea where he burned Atlanta. And that's why Atlanta has the image of the Phoenix as a symbol.

Orlando Montoya: Resurgens.

Peter Biello: Resurgens. Resurging from the ashes.

Orlando Montoya: The name on the city seal.

Peter Biello: So from Atlanta, the army marches southeast to Savannah. Along the way, formerly enslaved people who had escaped their plantations — maybe their plantations were burned or captured or looted. They start following the Union Army and they essentially trail behind them along the way.

Orlando Montoya: So how did they know they were able to follow this army?

Peter Biello: Well, there was legal precedent by that point. In 1864, Bennett Parten explains that.

Bennett Parten: It begins in 1861 with a law known as the First Confiscation Act, which treats enslaved people as confiscated property. However, the distinction there is that only enslaved people who claim to have been forced to work for the Confederacy in some capacity were given refuge within the Army's lines. After that, about a year later, more and more enslaved people continue to flee to the army. This becomes a problem for the army and also the U.S. government. Congress passes a humdrum bill known as the Second Confiscation Act, which is essentially an emancipation declaration. It is Congress's way of saying the enslaved people who come to army lines are considered thenceforth and forever free.

Peter Biello: So essentially there was an incentive for these folks to hook up with the army. They were considered free once they did.

Orlando Montoya: So I've heard all kinds of numbers about how many people this march entailed in terms of the number of newly freed enslaved people that were following the army. How many does he say it was?

Peter Biello: Of course, the number grows and shrinks depending on what happens along the way. But by the time they got to Savannah, there's an estimate of about 20,000 formerly enslaved people who are trailing the army.

Orlando Montoya: This was a problem.

Peter Biello: It was a problem in the sense that, you know, these people needed food and sometimes shelter. Most weren't traveling in covered wagons. They were on foot. And we're talking November, December 1864. It's cold, rough times out there. And of course, there are also Confederate troops still in Georgia that could possibly attack the army and take back these formerly enslaved people. But Bennett Parten also writes that the Union Army soldiers were in unfamiliar territory — Middle and East Georgia — and the formerly enslaved people knew the landscape better than they did, and they were active participants in the army's function.

Bennett Parten: They acted as scouts, as spies, as intelligence agents. They pointed the ways down hidden footpaths. They — they were able to offer information about where the Confederate Calvary was. The best story is what happens when Sherman's foragers arrive on these plantations and are looking for hidden plantation goods, be it livestock, food or what have you. Because it's enslaved people who are forced to do some of the hiding of these goods, they knew where all this stuff was. And so they were very, very willing to lead the soldiers out to a corral in the woods or to the family cemetery where trunks were buried. And this gave them real power and real agency in the march.

Peter Biello: Parten also says that as they got closer to Savannah, the plantations weren't as bountiful, not as much to — to loot from them. But the formerly enslaved people taught the army how to husk rice and consume it. And they also served as laborers, which was really an important part for Sherman. He didn't want these people to slow down the army or put the army at greater risk than they otherwise would be. And of course, I don't want to give the impression that Parten describes the Union Army as like 100% saviors of these people. Some among the Union Army were really not welcoming for these folks and did not want them around. Made that clear in a variety of ways, some of which were rather unkind.

Orlando Montoya: Well, we haven't even gotten to Ebenezer Creek yet. Does he get to Ebenezer Creek?

Peter Biello: He does write about Ebenezer Creek. So the army's marching along with the formerly enslaved people trailing behind. And one malicious leader of the Union Army ordered the destruction of the bridge over Ebenezer Creek, essentially stranding the formerly enslaved people on the wrong side of the creek as the Confederates were approaching, essentially leaving them to be slaughtered.

Orlando Montoya: Ebenezer Creek, just outside Savannah. And you should know that in Savannah this episode is very well-known.

Peter Biello: I haven't spent a whole lot of time in Savannah, so this was new to me and particularly horrific. And Parten describes it well in this book.

Orlando Montoya: But it then leads to good things in Savannah. What happened when they got to Savannah?

Peter Biello: Well, the army got to Savannah. Obviously, Savannah didn't burn the way Atlanta did. If you've ever been to Savannah —Orlando, we know you have — the city is remarkably well-preserved. Sherman famously presented Savannah to Lincoln as a Christmas gift, but the trail of refugees were mostly outside the city limits, and they were put on the sea islands on the coast.

Orlando Montoya: And that's the crisis part.

Peter Biello: That is the crisis part because here you have thousands of people, no connections to the area, no resources, no wealth to speak of with only as much as they can carry. And they're almost completely dependent on the powers that be. And the army has to decide, OK, so what do we do with these people?

Orlando Montoya: OK, I know what they do with these people.

Peter Biello: You know what they do.

Orlando Montoya: So tell — tell everybody.

Peter Biello: OK. So there was divided opinion on what should happen here. And it kind of struck me, reading this book, that the divide among people back then was kind of similar to how you might expect people, any group of politicos to divide themselves up today. There were people who said they need to sustain themselves, no help from the government. And then there were people who said they need to ease their way into society by working on land that white people own, but not by force, but for pay. And then there were people who said, let's give them the land, let them work it themselves, create generational wealth, help them when we can, and let them be as self-sustaining and independent as possible.

Orlando Montoya: And there were some experiments to that regard.

Peter Biello: Yeah, the Port Royal experiment. This is — might be one of the ones you've heard about. This was a big part of the book. Port Royal and experiments like it basically took up the second half of this book.

Orlando Montoya: And we should say Port Royal is in South Carolina.

Peter Biello: Port Royal is in South Carolina, right. When we're talking about sea islands, we're not necessarily limited to Georgia here. Here's how Bennett Parten explains the Port Royal experiment.

Bennett Parten: It begins early in the war in the fall of 1861, when the U.S. Navy sails into Port Royal Sound and seizes the port there. And they do this because Port Royal is the deepest deepwater port on the Southern coastline. So the idea is if you can establish an outpost there, you can then use that to blockade Savannah and Charleston and use it as a base of command. And so when the Navy sails into Port Royal Sound, they are able to establish this foothold, but it forces the region's white inhabitants, the slaveholders, to take flight. They all evacuate, and they leave behind 10,000 enslaved people on the islands. This is still in 1861. So we are well before this evolution to embrace emancipation takes place. At the time, they are considered contrabands of war, not free people. But the fact that there are — the slaveholders there have all fled, it makes them free in a de facto sense.

Peter Biello: The Port Royal experiment essentially was already underway by the time Sherman got there, and it's — it basically becomes more of a federal program funded by a lot of Northern charities. Some send money, others come down and create schools, host religious services, administer humanitarian aid of various kinds.

Bennett Parten: But critically — and this is an important "but" — they'll also begin coercing, convincing enslaved people to go back to work on the plantations, not as enslaved people, but as wage laborers. And so the Port Royal experiment, this federal project is a really important moment early in the war that begins this transition from slavery to freedom. And it becomes a kind of model for what emancipation can look like on a much wider scale going forward.

Peter Biello: When Sherman arrives, Port Royal becomes the epicenter of the refugee crisis.

Bennett Parten: Maybe as many as 17,000 people are relocated to the islands from Georgia. These are the Georgia refugees. So this is — almost doubles the population overnight. There's a real lack of housing, of space, of resources. Food becomes a problem by March, end of February. There is a rampent spread of disease. And so as a consequence of Sherman's march in the refugee movement behind his march, and as a consequence of his decision to begin relocating the refugees to Port Royal, this self-contained freedman's colony, this experiment of sorts, really collapses in on itself.

Orlando Montoya: So what eventually happens to these people?

Peter Biello: Well, it's a sad story in my view. Confederates, because they don't pay their federal taxes after they flee, when the Union Army advances, that essentially gives the Union legal rights to seize the land and do with it what they want. And there were plans to allocate the land to newly freed people. They want that land, too. They want to work. And the land was distributed along the coast in parcels roughly from Wilmington, N.C., to Jacksonville, Fla. But then Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson becomes president. And Johnson pardons all the Confederates and takes steps to give them back their land.

Bennett Parten: I think the number is close to 40,000 families are settled on about 400,000 acres of land by the summer of 1865. And then in 1866, there is a steady chipping away at land claims by formerly enslaved people on the islands.

Peter Biello: And of course, history shows us that Reconstruction never fully creates equality and safety for the freed people, despite constitutional amendments. So reading this book, you just got to imagine how much different life could have been for millions of people today, had the U.S. government honored their commitment to those freed people back then.

Orlando Montoya: All right. So what gives the book the Narrative Edge?

Peter Biello: So the book is sharp. It has a narrow enough focus so that you can really learn about this specific thing without getting bogged down in the details that historians are more interested in than the general public is interested in. I should say that this book is only about 200 pages. Right? Which is — gives it the kind of a digestible scope, I feel like. And that narrow focus really helps here. The language is clear. The storytelling is solid. I mean, there is an arc. It's not your traditional American road story, but it is a story. And these people are going from Atlanta to Savannah and stuff's happening along the way. And we talk about refugees and crises, but this one was right here in Georgia. And he's honest about the government and the military's shortcomings and how they handled it. Now, fun fact, too, about this book: This was his Ph.D. thesis, as I mentioned, written during COVID. So that's one way to spend your lockdown, right? Writing about Sherman's march and what it meant for emancipation.

Orlando Montoya: You got to pursue your passion.

Peter Biello: Yeah. Well, he's clearly passionate about this. Really knowledge — knowledgeable. Fun to talk to. Great book.

Orlando Montoya: Well, the book is Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman's March and the Story of America's Largest Emancipation. Peter, thank you for telling me about it.

Peter Biello: Happy to.

Orlando Montoya: Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at gpb.org/narrativeedge

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the daily GPB News podcast Georgia Today for a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts

A groundbreaking account of Sherman’s march to the Sea — the critical Civil War campaign that destroyed the Confederacy — told for the first time from the perspective of the tens of thousands of enslaved people who fled to the Union lines and transformed Sherman’s march into the biggest liberation event in American history.