Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: Between the Sacred and the Profane - Soul Music's Gospel Origins

Primary Content

In this episode of Salvation South Deluxe, Chuck talks with legendary singer-songwriter William Bell about his origins, and delves into the role religion played in creating Soul Music, one of America's greatest ever contributions to culture.

TRANSCRIPT:

Chuck Reece: Late every Saturday night in the South, something magical happens. In the wee hours. In the…"between time."

The last of the tipsy stragglers who have danced and flirted and partied almost all night long are just making it home. And only an hour or two later, the folks who went to bed early so they could make it church on time are just waking up.

It’s that hour when the Saturday night profane is giving way to the Sunday morning sacred.

Two kinds of people. One who wants to rejoice in their body. One who wants to rejoice in their soul.

Except we all know that life never breaks down into neat little categories like that: the party people and the worshipful people. Most of us, truth be told, are both. We are sometimes raucous, sometimes prayerful. Sometimes earthly and sometimes heavenly. Sometimes sacred and other times profane.

Me? I think that’s okay. I think that’s JUST DANDY. Because those magical moments — as Saturday night bleeds over into Sunday morning — have produced some of the greatest cultural treasures the American South has ever given to the world.

And today, on Salvation South Deluxe, we’re going to chat with somebody who created some of the exact treasures I’m talking about. And we’ll hear him tell us how his journey to musical stardom started on the Sunday morning side of the line.

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we’re adding to our podcast feed that unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience, narrated by the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

MUSIC: William Bell - "Every Day Will Be Like a Holiday"

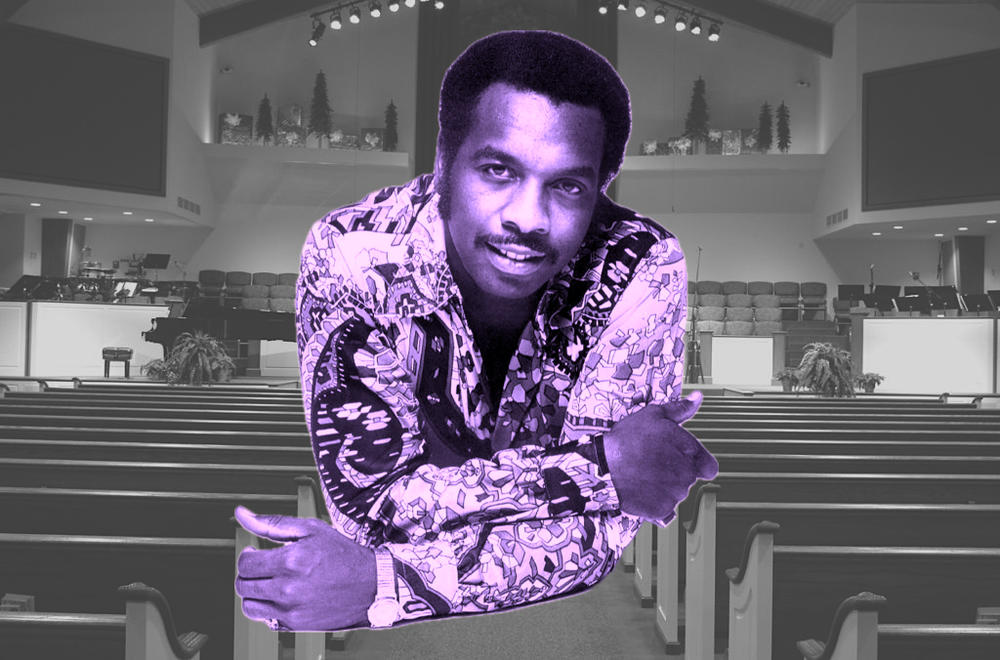

Chuck Reece: That is a song from 1967 called “Every Day Will Be Like a Holiday.” It was written and sung by William Bell. William was the first male solo artist ever signed to Stax Records.

Stax Records on McLemore Avenue in Memphis, Tenn., is a very important site in the cultural history of the American South. It was one of the three primary birthplaces of a musical genre that came to be known as soul.

The other two, which we will address in later editions of Salvation South Deluxe, are Muscle Shoals, Ala., and Macon right here in Georgia.

Six years before “Every Day Will Be Like a Holiday” hit the radio airwaves in '67, a young man just 21 years old named William Yarbrough walked into Stax and signed that record contract. He took the stage name William Bell, B-E-L-L, to honor his grandmother, whose name was Belle: B-E-L-L-E.

And he distinguished himself not only as a performer, but as a songwriter. No discussion about the Southern soul music of the 1960s is complete without William Bell. He wrote hits for himself, like that one, and for many other great artists.

Like Albert King.

MUSIC: Albert King - "Born Under a Bad Sign"

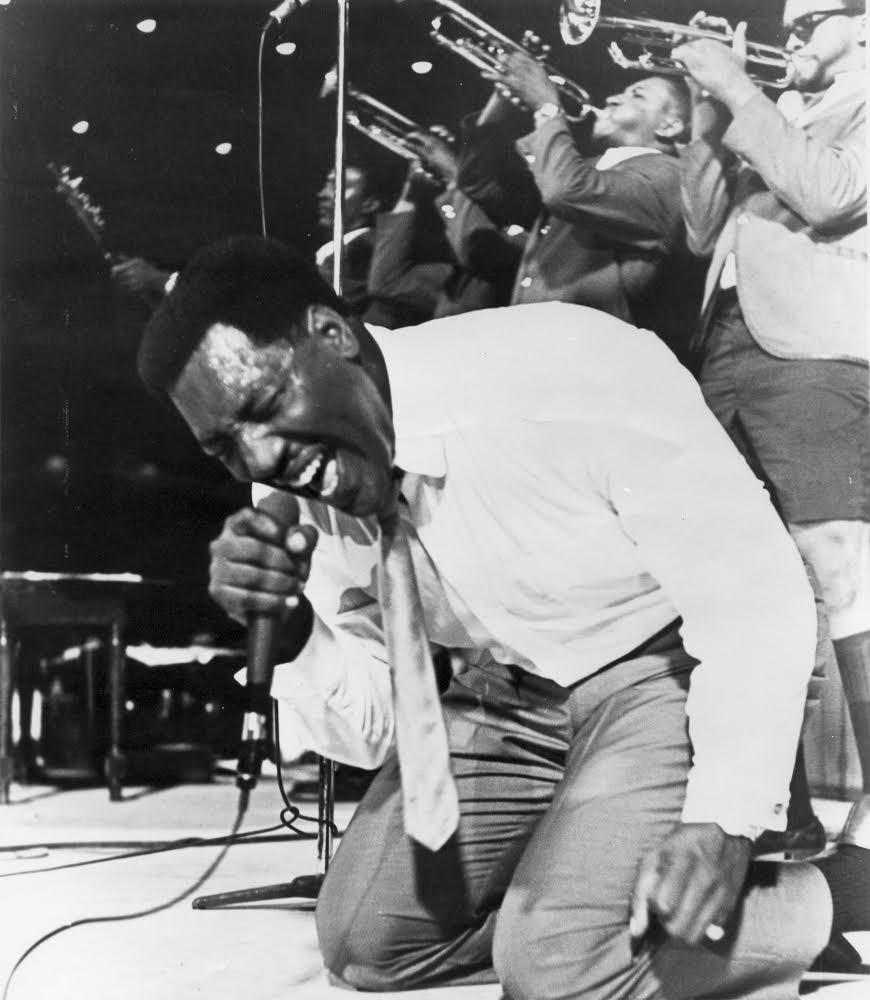

Chuck Reece: And Otis Redding.

MUSIC: Otis Redding - "You Don't Miss Your Water"

Chuck Reece: When William signed that first contract with Stax, he could not have understood the magnitude of what he was walking into. He was about to become part of the creation story of soul music, one of the greatest achievements in the history of Southern culture.

At the time, in 1961, that phrase — “soul music” — was just coming into the American vernacular. The earliest documented use of the term is a 1961 reference in the Los Angeles Sentinel. That Black newspaper that called Georgia-born Ray Charles, and I quote, a “soul-music genius.”

The term “soul” arose because many Black musicians, whose work was crossing over to appeal to young white people, had their musical roots in the Black churches in which they had been raised.

Now let’s pause for a second to think about that word. “Soul.” Why, the idea itself is the province of the church.

Here’s a line from the book of Deuteronomy: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might.”

Artists like Charles, starting in the late 1950s, were turning the rhythms and vocal styles and even the language of gospel music toward the concerns of Saturday night.

MUSIC: Ray Charles - "Hallelujah I Love Her So"

Chuck Reece: Speaking of church, that Ray Charles tune was the very first single ever to hit the Billboard pop charts with the word “hallelujah” in its title. It makes sense, because Aretha Robinson — the mother of Ray Charles Robinson — made sure her son sang in the church choir.

And like young Ray Charles in Georgia, William Bell was raised in the church in Memphis.

William Bell: Absolutely. Same story. I started in church around 7, singing with the choir there in church with my mom. My mom was in the choir. And around 9 I kind of graduated out singing solo with the choir behind me. But —

Chuck Reece: Oh wow!

William Bell: I started in the — in the Baptist church, there in Memphis.

Chuck Reece: In the '40s and '50s, there was a whole lot of pretty amazing gospel quartet music around that time, you know, like the Soul Stirrers and the Dixie Hummingbirds ...

William Bell: The Fairfield Four, yeah, and Dixie Hummingbirds, all those guys. Yeah.

Chuck Reece: You were listening to those people, too?

William Bell: Absolutely. My favorite was Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, though. Even to this day, they had just intricate harmonies and Sam had a way of telling a story with the lyrical content and ad libbing on it and just had a wonderful tone to his voice. So the Soul Stirrers were my favorite group.

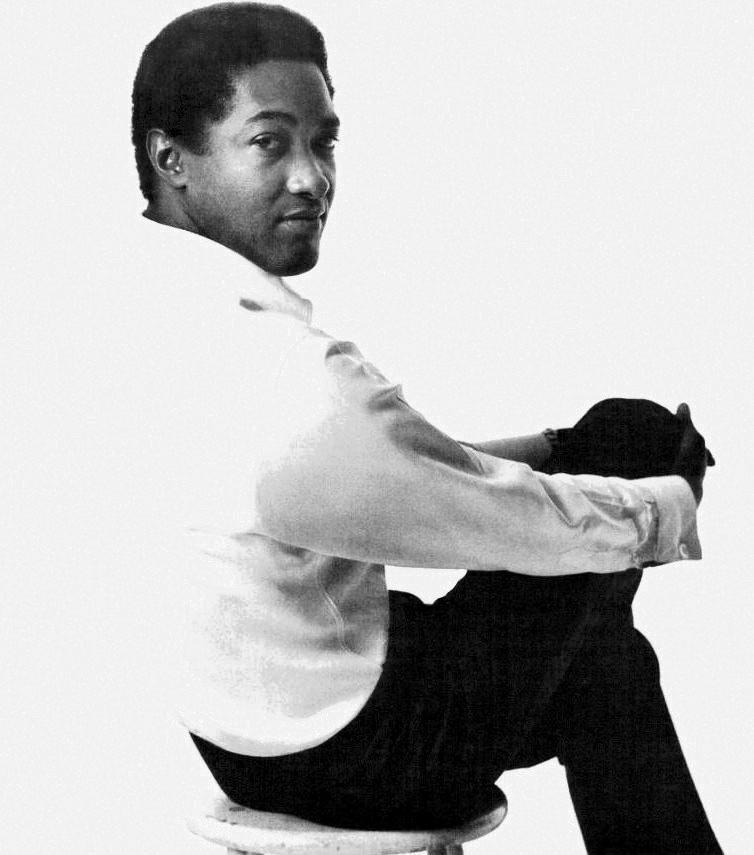

Chuck Reece: Sam Cooke, who was born in 1931 in Clarksdale, Miss., joined the Soul Stirrers, as their lead singer, when he was only 19 years old, in 1950. The Soul Stirrers had already been around for nearly 25 years, but after Cooke’s unforgettable voice took the lead, the group soared to new heights of popularity.

MUSIC: Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers - "Jesus Gave Me Water"

Chuck Reece: But seven years later, in 1957, Sam Cooke made a decision that made a lot of churchgoers angry. He decided to leave gospel music and go pop. And you know … hey, we ALL know … his first hit.

MUSIC: Sam Cooke - "You Send Me"

Chuck Reece: So here we are in 1957 and William Bell, now only 18 years old, has just watched his gospel music hero, Sam Cooke, step over on to the pop charts. And William was already on his way to making the same move. He had already formed a little doo-wop singing group called the Del Rios.

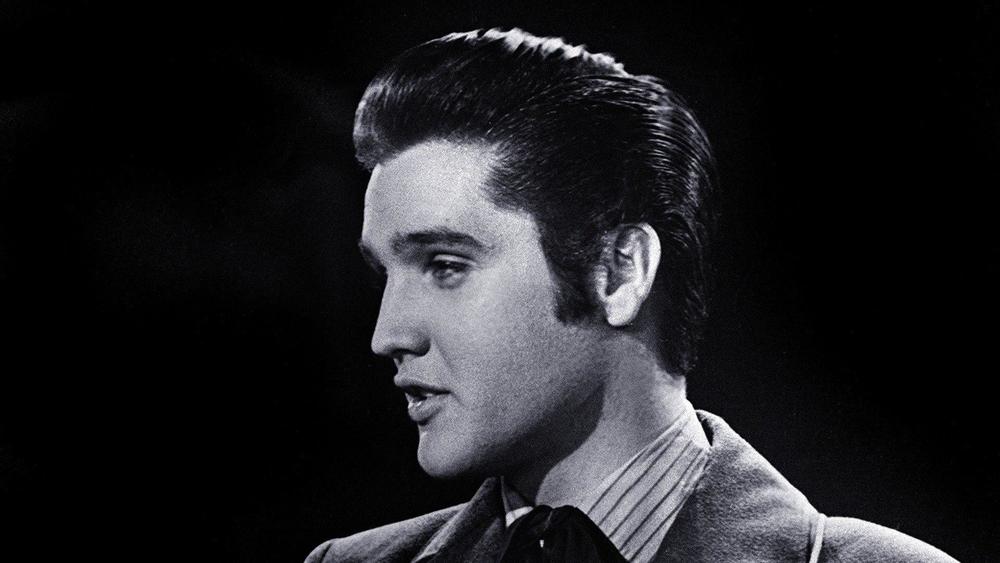

William spent a lot of time in those days hanging out with a young white musician named Chips Moman, who would later go on to an amazing career of his own as a producer and songwriter. The pair liked to hang out at Memphis Recording Service, a studio founded in 1950 by a man named Sam Phillips. Sam’s place became famous in 1953 when another young Memphis man — Elvis Presley — made his first recordings there for Sam’s label, Sun Records.

William Bell: I knew — Chips Moman and I would hang out sometime at Sam Phillips’s studio, over at Sun. We knew Elvis. Elvis used to come down to the Flamingo Room and sit in the back while we were singing and watch us perform. But we all knew each other. George Kline, who was Elvis's buddy, introduced us, and George and I were good friends from since I was a teenager. We did his Christmas shows on television for him. So we always just mixed up there: Jerry Lee, and, like I said, Ronnie Milsap was there at the time, and Dickey Lee and just a host of other acts coming up.

Chuck Reece: So think about this. Here is a young Black musician in 1961: Three years before the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Jim Crow laws in full force. But inside the Sam Phillips’s Sun studios, the color line didn’t matter.

William Bell: Sun Records didn't care. They just — all they cared about was what you brought into that studio in terms of creativity. If you could write, you could sing, you could play, whatever the situation was. We wanted you to do the best that you could. And we just got together inside those confines of the studio, whether it was Sun or Stax, and had a great time.

Chuck Reece: White guys like Chips Moman and Elvis Presley. Black guys like William Bell and Booker T. Jones, who cowrote “Every Day Will Be Like a Holiday” with William. They just wanted to make great music together. They had that in common.

And they had something else in common: they had all grown up singing in churches — and listening to gospel quartet music on the radio. While William was into Black groups like Sam Cooke & the Soul Stirrers and the Fairfield Four, Elvis was listening to white groups like Georgia’s Hovie Lister & the Statesmen or Mississippi’s Blackwood Brothers.

Chuck Reece (on tape): It's funny, I grew up hearing the quartet music, but mostly like, you know, because we were kept apart back in those days.

William Bell: Right.

Chuck Reece: You know, I was listening to Hovie Lister & Statesmen and the Blackwood Brothers and people like that.

William Bell: Yeah. we did, too!

Chuck Reece: Well, you know, I learned — after growing up in that because my dad sang bass in quartets, in several different ones — and, you know, when I got a little older, I learned we were singing a lot of the same songs.

William Bell: Absolutely.

Chuck Reece: We just weren’t doing it together.

William Bell: Absolutely. And then in the proof of the pudding to that is Elvis. Elvis used the Statesmen and different people behind him for a while. We understood where they were coming from, because most of the Black acts at that time — and the white acts — were right out of church. And that's why we cut out our tenure and everything, our eye teeth in church. And it was good training for lyrical content, the making of feel of a story and the lyric and continuity and all that stuff. It was just great training.

Chuck Reece: In those songs was, I-I guess you would have to call it sort of a feeling of transcendence. Like, you know, you think about a song like “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” for instance.

MUSIC: Elvis Presley - "Precious Lord, Take My Hand"

Chuck Reece: So much feeling in that song. And I guess it just makes sense that that when you take people who grew up on stuff like that and and put them in a studio to make, you know, secular music, the same kind of feeling is going to bleed over.

William Bell: Absolutely. And, you know, the same people that worked hard all week and went to — out to party on Saturday night, let their hair down, they were in church on Sunday morning, those same people. And so when the music of — secular music came into play, it was from the gospel singers. It just made sense. That’s Black and white, you know. And it just made sense that we were singing to the same people, just a different venue with a different lyrical content, but with that same musical approach. I guess that's why they call it soul music, because you sang at any given time what you were feeling at the moment so to tell that story.

Chuck Reece: You talk about you guess that's why they call it soul music. I mean, was that term even in usage? When you first started working at Stax in the late '50s and early '60s?

William Bell: No, it was either rockabilly — if it was the white acts, it was country music/rockabilly and the black music was jazz, blues, rhythm and blues. When you put a beat to it and they could dance to it. But it was the same music from the same people. The guys out of Mississippi in Louisiana, New Orleans places, the same music. They were all out of church. Most of the artists, their parents were either preachers or deacons or something in the church, and they were in church on Sunday morning. But to make some money and make some extra money, including B.B., he would, he would, he would go out on the street and sing, and he made more money in his hat — he made more money in his hat than he was making, you know, trying to do gospel music. So he figured out, well, okay, I could sing blues. It's just changing the lyrics. A lot of the original early blues stuff came out of the church music. I mean, Sam Cooke, you know, even his stuff was just original. That's why the church people were so angry with him because he was taking gospel music, changing the lyrics to it, but with the same melody and making hits out of it.

Chuck Reece: Talking specifically about Sam Cooke. I think there's a good argument to be made that “A Change Is Gonna Come” could be read as a gospel song, too.

MUSIC: Sam Cooke - "A Change Is Gonna Come"

William Bell: Absolutely. And I think he kind of meant that because he had listened to Bob Dylan's “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and he was — he always felt he should have more significance like that, like “Blowin’ in the Wind.” And so he created “A Change Is Gonna Come.” And to me, when you listen to that as a reference, to how he expressed it, how he felt it and the lyrical content too. So it could very well be what we call pseudo-gospel.

Chuck Reece: Right. It is because it's got that feeling and it's uplifting.

William Bell: Yes.

Chuck Reece: It’s…It makes you feel like things can get better.

William Bell: Right. And there's always hope.

Chuck Reece: One of the most amazing things to me is how persistently popular the music that y'all were making back in those days in Memphis just continued to be. It's like generation after generation grew up dancing to it.

William Bell: Because humans … people are people and that's the world over. The human nature of people. The times change, the living conditions might change. But the human factor on how you deal with living remains the same. And so people can relate to something if there's real — if he's real about it and you're telling the truth about how it feels to be left alone by your loved one, or how it feels to be discriminated against or whatever the situation is. If you feel that you do an honest job of that, no matter what generation you are, and when you start communicating with other individuals, that same feeling is gonna creep in. And that's in every country. And I've traveled extensively and sometimes in countries that people don't even understand the English language. They feel what you portraying and what you're trying to project in the way you sing a lyric.

Chuck Reece: Right.

William Bell: Just the same as we do when we listen to opera. Sometimes I listen to “Madame Butterfly” or something and I don't understand. I understand what I call “survival Italian,” but I don't understand fluent Italian. But I can listen to an opera and I understand it because of the emotional value of it. And that's the same thing that people do in every generation and every race, creed, or color. We all have the same wishes, frustration, desires or whatever.

Chuck Reece: Right there. There it is: We all have the same wishes and frustrations and desires. Regardless of what we believe or the color of our skin.

And I think what William is telling us is that when people reach down inside themselves — really try to dig in and try to express what they feel and what they desire from the very core of their being — then they can make music that shakes us; music that can rightfully be called the music of the soul.

As we were putting this episode together, there was an odd coincidence. I was doing a crossword puzzle, and there were two parallel clues. One was “The inner self, in psychology.” The other was “The inner self, in religion.”

The answer to the psychology clue was EGO. The answer to the religion clue was SOUL.

And there in that liminal space, in the wee hours between Saturday night and Sunday morning, when we sit right on the dividing line between the ego and the soul. Between the innermost desires of our bodies and the innermost desires of our souls.

Six decades ago, in the American South, Black artists and white artists together created music of the soul. And they chose to call it “soul music.” Because it expressed our whole selves — the Saturday night side and the Sunday morning side.

And one of those people was William Bell. Since 1969, William has lived in the fair city of Atlanta, not far from where we recorded this episode. And today, 63 years after he signed that contract with Stax Records, his career as a professional singer, songwriter, and producer is still going strong. William’s most recent album, One Day Closer to Home, came out last year. You should buy a copy. It is filled, to use the word of the day, with soul.

MUSIC: William Bell - "I Still Go To Parties"

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank Mr. Bell for his time and consideration. You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of 20 stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and we periodically add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com

Our producer is the mighty Jake Cook, who also composed our theme music. GPB’s senior podcast producer is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without wonderful people like GPB’s Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Deluxe podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.