Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning

Primary Content

In this episode of Salvation South Deluxe, Chuck talks with Grace Elizabeth Hale, author of In The Pines: A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning. Through her story, Chuck explores the meaning and truth behind the character Atticus Finch as the Southern hero archetype.

TRANSCRIPT:

Chuck Reece: Dear listeners, I have a favor to ask of you. I’d like us all to take a deep breath. Let’s calm our minds. I want us to conjure up — together — a clear image of a genuine Southern hero.His first name is Atticus. His last name … well, you know it … Finch.

Imagine him standing in that courtroom in Maycomb, Alabama. About six foot three. Dark hair. Wearing those timeless horn-rimmed glasses. Impeccably dressed in a dark suit. A white man defending a Black man who has been wrongly accused of rape.

Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch (from "To Kill a Mockingbird"): In this country, our courts are the great levelers, and in our courts, all men are created equal.

Chuck Reece: You and I both know the man we conjured up was Gregory Peck. We all know that Atticus Finch was a fictional character in a film made sixty-two years ago called To Kill a Mockingbird. And we all know it came from a Pulitzer Prize-winning book published two years earlier by the brilliant Alabama writer Harper Lee.

But for decades, thousands of Southerners — particularly white Southerners like me who believe they have an enlightened view of race — have wanted … needed, even … to have an archetypal hero somewhere out there like Atticus Finch.

And I wonder, why do we feel that need?

Joseph Crespino: We are story-making people. You know, psychologists talk about this. Novelists talk about this. We make sense of our experience by telling stories. We need to tell stories that make sense of the world.

Chuck Reece: That’s Joseph Crespino, the Jimmy Carter Professor of History at Emory University, who six years ago published a book called Atticus Finch: The Biography. Joe’s fascinating book gave us the details of how the brilliant Alabama writer Harper Lee came up with the character of Atticus.

In that book, Joe writes,

Atticus Finch is a hero because he vigorously defended a black man wrongly accused of raping a white woman. He did it because it was the right thing to do, pure and simple.

Joseph Crespino: For, you know, certain white southerners, who feel very conflicted about the region in which they grew up, in the history of racial discrimination, the history of white supremacy, and whose families are implicated in that history. It is, to me, human and natural and not surprising that they would, gravitate towards and, be compelled by stories of people who had come before who also recognized the injustice of that society, and tried in some way to make some contribution and to do something about it.

Chuck Reece: Another Southern professor of history, a Georgia native named Grace Elizabeth Hale of the University of Virginia, wanted … as so many of us do … a hero like Atticus Finch. But unlike so many of us, Grace actually had one. Her very own grandfather.

And then, later in life, she discovered that her Atticus, too, was just a piece of fiction.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed hoping to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

Grace Hale’s story will be familiar to many who grew up in the suburbs of big Southern cities. There’s a good chance your parents grew up in the country — and kept strong connections to the places they grew up.

Grace grew up in the Atlanta suburbs but spent big chunks of time in the summer with her grandparents, Grace and Oury Berry, in Prentiss, Mississippi.

Grace Hale: Like so many Southerners, white and black. You know, my parents would send us back home to visit, so I wouldn't spend the entire summer, but I'd spend chunks of it there. And I really loved to be there. And so I was always eager to go and, you know, I, I spent a lot of time with my grandfather. You know, in my girlhood, because my grandmother worked at the Chancery clerk's office, and so I would spend a lot of time with my grandfather just driving around all over Jefferson Davis County.

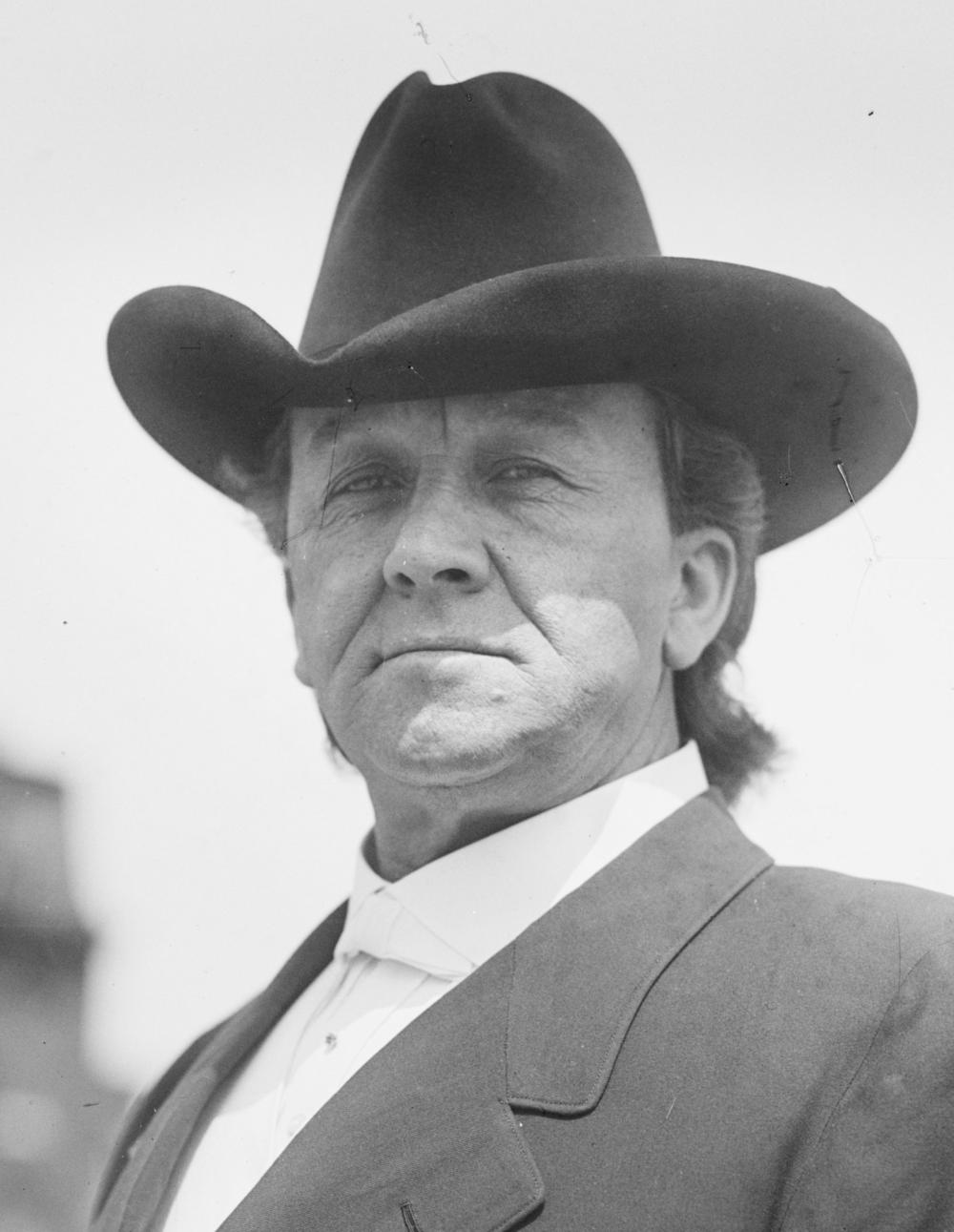

Chuck Reece: Jeff Davis County had been carved out of two other counties in nineteen-oh-six to create a majority Black county. If you detect some irony in the fact such a county was named after the president of the Confederacy, you are absolutely accurate. And you can blame that on James K. Vardaman, who was governor of Mississippi at the time and who was known as “the great white chief” for his advocacy of white supremacy.

“If it is necessary,” Vardaman said, “that every Negro in the state be lynched, it will be done to maintain white supremacy.”

Grace Hale: I grew up in suburban Atlanta, and I felt like the places that I grew up were, were all sort of "non-place" places. You know, they were so recently constructed and there just didn't seem to be any kind of sense of history. And, you know, I don't think this is entirely fair, but that was my perception as a child. And I just found being in this small town in Mississippi, Prentiss, where you could walk everywhere, where most where most people knew each other, there was a kind of freedom that I had.

I fell in love with just how much it seemed like there was history there, that there were layers there, and that my grandfather had a kind of key to those layers that he had some sense of them from, probably talking to his own older relatives and just from living there so long. My grandfather was a great storyteller. He had lived in that county all his life, and he just knew so many wonderful tales. The historian in me would say now, probably some of them, many of them not true, but nevertheless that were that were rolled out as history to me as a child. And it really made me very, very interested in the past.

Chuck Reece (from studio interview): It's pretty clear that you loved him deeply. Is that a fair statement?

Grace Hale: Absolutely. … I did love him deeply. I still love him. I mean, he's been dead a long time, since I was about 15 or 16. But, you know, I loved him and still … still do.

Chuck Reece: After Grace entered college at the University of Georgia, her mother told her a story that elevated her late grandfather into a hero in her eyes. Not just a family hero. But a hero of, shall we say, Atticusian proportions.The story dated back to fifteen years before Grace was born. To the late nineteen-forties, when her grandfather, Oury Berry, had been sheriff of Jeff Davis County. Grace tells this story in her new book, In the Pines.

Grace Hale: I think I was about 20. I was home from Athens. … I was talking about history, you know, something that I was studying or thinking about. And she brought up this story that was really straight out of To Kill a Mockingbird, Of her father as Atticus Finch, you know, as the brave man who had taken his gun to the jail and sat up all night and kept the mob from taking a Black man from that facility. … And that was a huge part of why, when I went to graduate school, some of the first very serious research I did — that was part of my first book — was about lynching.

Chuck Reece: The history of lynching in the South is, of course, a long and sad one. Alabama’s Equal Justice Initiative has so far documented over four thousand racial-terror lynchings in the region between eighteen-seventy-seven and nineteen-fifty.

But on one night in nineteen-forty-seven, Grace Hale’s grandfather had stood in the way of a lynching. Oury Berry and his deputies earlier that day had arrested a Black man, Versie Johnson, after a pregnant white woman accused him of attacking and raping her. That night, Grace’s mother told her, he sat up through the wee hours, outside the jail with a gun, to stand down any locals who might have a mind to lynch Versie Johnson.

Here is how Grace writes about what her mother told her.

By evening, a crowd had gathered outside my grandfather’s office in the courthouse. Carrying his pistol, my grandfather walked outside to speak to the armed and sweating men. ‘I’ve known most of you all my life,’ he said, just like Gregory Peck playing Atticus Finch, ‘but no one is taking a man out of my jail.’ Willing to uphold the law even against the people who voted him into office, my grandfather prevented a lynching, my mother told me. He was a hero.

Years later, with the dissertation for her doctoral degree almost finished, Grace traveled back down to Mississippi to visit her namesake, her ailing grandmother. By now well schooled in the historian’s method, Grace visited the local newspaper, the Prentiss Headlight, to learn the details behind the story of heroism her mother had told her. But what she learned that day, Grace writes, “upended what I thought I knew about my grandfather and left me with a feeling of cold terror.”

We’ll be back with more of Grace’s story, right after this break.

MIDROLL BREAK

Chuck Reece: Joe Crespino is careful to remind us that the Atticus Finch we saw in the movie differs greatly from the one we met in Harper Lee’s book. To Kill a Mockingbird, the book, was really, at its heart, a coming-of-age story about Atticus’s two children, Jem and Jean Louise, the tomboy who preferred to be called Scout. But when Hollywood bought the rights to Lee’s book, it needed a star. Not a child actor to play Scout, but a big name.

Joseph Crespino: They needed someone to be the lead, the name on the movie poster. And so Atticus inevitably moves to the center of the story in the movie. And he is unambiguously a heroic figure because of the demands of Hollywood storytelling.

Chuck Reece: The end result of all that means that that character on the screen, who was so firmly lodged in the minds of Americans, is a character who probably could not have existed … in the course of 20th century white supremacy in the South. …

Joseph Crespino: Yeah. I mean, he's an invention of Hollywood.

Chuck Reece: Grace Hale still does not know exactly who invented the Atticus Finch version of her grandfather, Oury Berry. She only knows that on that day in the nineteen-nineties, when she visited the office of the little newspaper called the Prentiss Headlight, the invention fell apart.

Grace Hale: I had that story always circulating in my mind that I had that I had had for a long time from my family of my grandfather being a hero in this incident. And so since I was in grad school and had really learned how to do that kind of research, it just seemed a natural thing to do to head off to, you know. … And dig into the, you know, just dig into the back issues, the bound copies of the newspaper. I just thought that it would be interesting to see what the paper had had to say about this story that I'd grown up with, of my grandfather's heroism.

Chuck Reece: She already knew from her mother’s story that the morning after her grandfather supposedly stood down the lynch mob, he was at home, asleep, when the accused Black man, Versie Johnson, asked to be taken to the scene of the crime to explain what had happened. While there, Grace’s mother had told her, Johnson tried to grab a deputy’s gun, and had been killed.

But what she discovered on that day almost thirty years ago in the newspaper officei, changed Grace Hale’s life forever.

Grace Hale: It was a very, very difficult moment. … I found an article on the front page of the newspaper, the weekly. So it was … you know, almost a week after this incident had happened. But reading that article, I found out the date that the incident happened, which was August first, nineteen-forty-seven. And I found out the name of the black man who had been imprisoned and then later shot, and that was Versie Johnson.

But there were, there were signs there though, that what the newspaper was reporting wasn't true. So two things were going on in my mind simultaneously. One, this is not the story that I grew up with. This is … not wildly different, but it is a different version of events than I grew up with. So that hit me. But also I had my scholar’s sort of self there as well as my, you know, …'this is my family' self there.

And I knew sort of what to look for, like how white people talk about these things, cover things up, lie about them. I knew what those clues were. I knew what to look for. … And probably the most powerful one, for me at least, was that the newspaper insisted that Versie Johnson had asked to be taken out of the jail, back to the site of the alleged crime so that he could explain what happened. Anybody that knows anything about the history of racial violence in the South knows that no Black person asked to be taken out of a jail and out into the countryside if they have been accused of a crime that white people are going to be really upset about. And Versie Johnson was accused of raping a white woman, so there is no way that he would have asked to be taken out of the jail.

Chuck Reece: Over the following years, Grace worked the story of her own family the way a brilliant historian should work on any history. She dug into every source of information she could find. She talked to everyone she could find, including the few still living who were there in Jefferson Davis County in the nineteen-forties. What she learned is that her grandfather had not been at home asleep on that morning of August second, the day after Versie Johnson was accused and arrested. She learned Johnson had not asked to be taken back to the scene of his alleged crime. She learned that Oury Berry, her own grandfather, had not faced down a mob of white men bent on lynching the night before.

No, the mob had actually appeared the next morning, at the alleged crime scene. And Versie Johnson had been removed from the jail and taken there by two Mississippi State Patrolmen … and one other officer of the law, Oury Berry, Grace’s grandfather.

Oury Berry had not been a real-life Atticus Finch. He had not been a hero. Not at all.

In that light, the subtitle of In the Pines takes on truly deep meaning. That subtitle is A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning. A reckoning is a settling of accounts, particularly for past injustices. Through that settling comes reconciliation — healing, the resolution of differences, the restoration of harmony. We have heard much over the past several years about the need for racial reconciliation in the South. This book made me look at our legacy of white supremacy at a deeper level than I ever had. Even after spending eleven years almost exclusively writing and telling stories about the South.

And it gave me a vision of what reckoning looks like inside a family.

Chuck Reece (from studio interview): I'm guessing that your mother believed that what she told you was absolutely true.

Grace Hale: She did. And she still does.

Chuck Reece: Has she read your book?

Grace Hale: I think she has read it … But she continues to believe the story. That is, the story that she says she grew up with — and that that's the true story.

Chuck Reece (VO): Because Grace weaves the broad history of white supremacy and lynching into this personal story of her family, I came to feel — in a truly visceral way — the thinking that poisoned the minds of so many Southerners still poisons the thinking of certain people all over America.

Grace Hale: It's useful to think about a deep, deep tradition — in the South, but really in rural America more broadly. It's a very old idea of the law as a kind of personal power that you hold in your hands. And of course, through much of that history, only certain people have had the right to hold that power in their hands. Most often it's white men. In an earlier era, it would have been white men of property. But white men have the right to think about the law as their own sort of physical embodied power. It's something that they literally hold in their hands. It's not something that resides in courts, and it's not rules and laws that are written down. … All of that is an abstraction. The law is the power that you hold in your hands, and that really comes from the experience on two fronts, wars against Native Americans and also enforcement of enslavement through slave patrols.

That sort of feeling that all white men have the power to police all Black people does not stop with the end of the Civil War and emancipation. And we see, you know, tremendous violence against Black people during reconstruction and then on into the period after that, where sometimes it's more organized. … The Klan is only one of many sorts of armed militia groups. And also, in less organized ways, that over time become the practice of lynching … sort of the sense that it's not vigilante violence because we are the citizens, and the law is what we say it is.

Chuck Reece: The law is what we say it is. I used to hear that kind of thing in old Western movies all the time, but never realized what a nasty tradition it represented.

Another reason I believe In the Pines is important reading comes from all the effort its author puts into documenting the life of the Black man who died on August first, nineteen-forty-seven, Versie Johnson.

Grace Hale: I really wanted to reconstruct Johnson's life and also the life of the community where he lived, because I don't think that you can understand … what is being lost if you don't understand both the personal family history of the person who was killed, but also that whenever there was an act of racial violence, it's an attack against the entire black community.

Chuck Reece: As I mentioned earlier in this show, Jeff Davis County was majority Black from the beginning, a hundred and twenty years ago. And many of the Black families owned their own land, their farms. They were like many white Southerners of their era. They were landowners who were self-sufficient, living off the crops and livestock they raised.

Grace Hale: There was a flourishing black rural world in many parts of the South and even some other parts of the country, despite the violence of Jim Crow. … And Jeff Davis County is one of them, and I didn't know much about that history before I started digging into it. And I think it's really, really important for us to understand, because a lot of what white people do in the Jim Crow South, acts of violence and other forms of oppression, are attacks on black success, not black failure, right? They're attacks on black success. … If you take Booker T. Washington's ideals and his vision, many black people in Jeff Davis County are living it.

Chuck Reece: In Grace’s book, there is a particular passage where, when I read it, I felt as if someone had whacked me with the cast-iron skillet of truth. Let me read it for you.

The federal government would eventually force places like Jeff Davis County to integrate the public schools, the franchise, employment and businesses and other facilities. Black people would win the enforcement of these citizenship rights. But paradoxically, in winning on one front, they would they would in time lose on another. Civil rights victories prompted a white backlash against the parts of the federal government that tried to guarantee black rights. By the end of the 20th century, black residents of Jeff Davis County would find themselves holding on to the hollowed out shell of what had been crumbling public schools, civic buildings and infrastructure that had previously been supported by local, state and federal funding. But after integration, they were slowly starved of resources across the nation. Too many white people reacted to the civil rights movement by turning against the very concept of the public. Rather than accept integration, they rejected democracy.

The Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts were not passed into law until the mid-sixties. And in the wake of that legislation, federal money poured into communities all over the nation with the goal of creating equal opportunities in public schools and in the use of public facilities. But in many rural communities, there remained among the white citizens a stubborn resistance to the idea of racial equality. Grace has the facts about Jeff Davis County.

Grace Hale: And so watching it play out, watching this, this area, this town, this county go from bragging about its facilities. Really, they could not celebrate more. For example, building a public pool right at the elementary school and high school. Local funds, like government funds, went into it. And also, frankly, you know, private clubs and groups raise money. … They were so proud of that pool.

Chuck Reece: Then, in nineteen-seventy, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ordered that all public schools in America be integrated. Immediately. But the resistance remained in so many counties across the South. Including Jeff Davis.

Grace Hale: As soon as they were forced to integrate the schools … they know they're going to have to integrate the pool … they they fill that pool in. They close that pool. Yeah. And … you just see that time and time again. So they have been so proud of having modern school buildings, having incredible facilities, having, you know, modern county offices, you know, all of that. They're very much invested in that … an infrastructure is the sort of signs of being part of the modern world. And as soon as they have to integrate those spaces and those resources, that all just disappears.

Chuck Reece: And it stays gone. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, from twenty-eighteen to twenty-two, the GDP of Jefferson Davis County fell by seven percent, while the GDP of the entire state of Mississippi grew by six percent. That belief that white people are somehow superior to Black people … and the rejection of democracy that comes with that belief … well, as my Uncle Efford used to say, “That don't do no good for nobody."

And it's also important to remember that choosing a hero, even one like Atticus Finch, can be dangerous business.

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank these two great Southern historians — Grace Elizabeth Hale and Joseph Crespino — for their help and cooperation in producing this episode. I did not tell you today the details of what happened in Jeff Davis County on the day Versie Johnson died, so I encourage you strongly to buy a copy of Grace's book, In the Pines: A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning. It was published by Little, Brown and is available at all your favorite bookstores.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I'm Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find twenty-four-seven at Salvation South dot com.

Our producer is Jake Cook. He also composed the theme music you’re listening to right now. GPB’s senior podcast producer is Jeremy Powell. And we never let of these episodes end without thanking the wonderful people of GPB who believe in what Salvation South is doing, especially Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.