Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: Hank Had A Hammer

Primary Content

In this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: we explore the storied life and career of Southern Baseball legend "Hammerin" Henry Aaron. Chuck Reece discovers the lasting impact of Aaron's legacy, and learns that Hank's yearning for social justice extended to the Baseball field and far beyond.

TRANSCRIPT:

Chuck Reece: In the nineteen-forties, America’s undisputed favorite pastime was baseball. Heroes like Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio inspired kids all over the nation. They begged their parents for bats and gloves. There was a brand-new organization called Little League Baseball, and kids rushed to join the local teams.

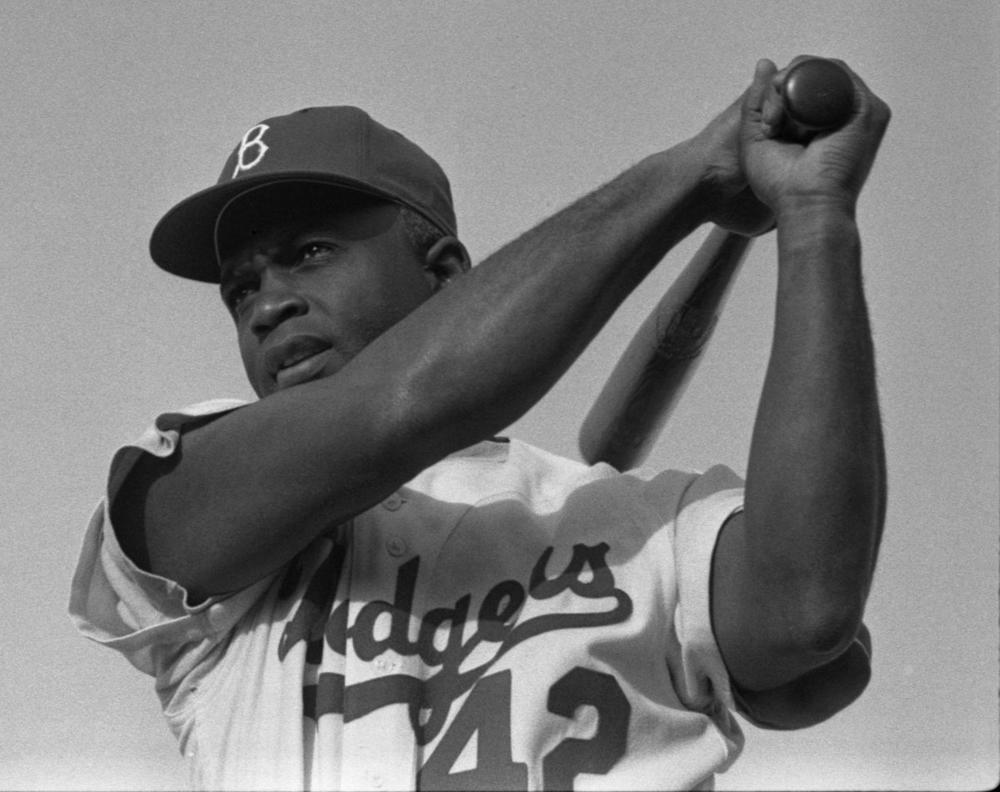

Some kids couldn’t join Little League teams, because their parents couldn’t afford it…or because their skin was the wrong color…or both. But they loved the game, anyway. And when Jackie Robinson finally broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball and joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in nineteen-forty-seven, he became their hero.

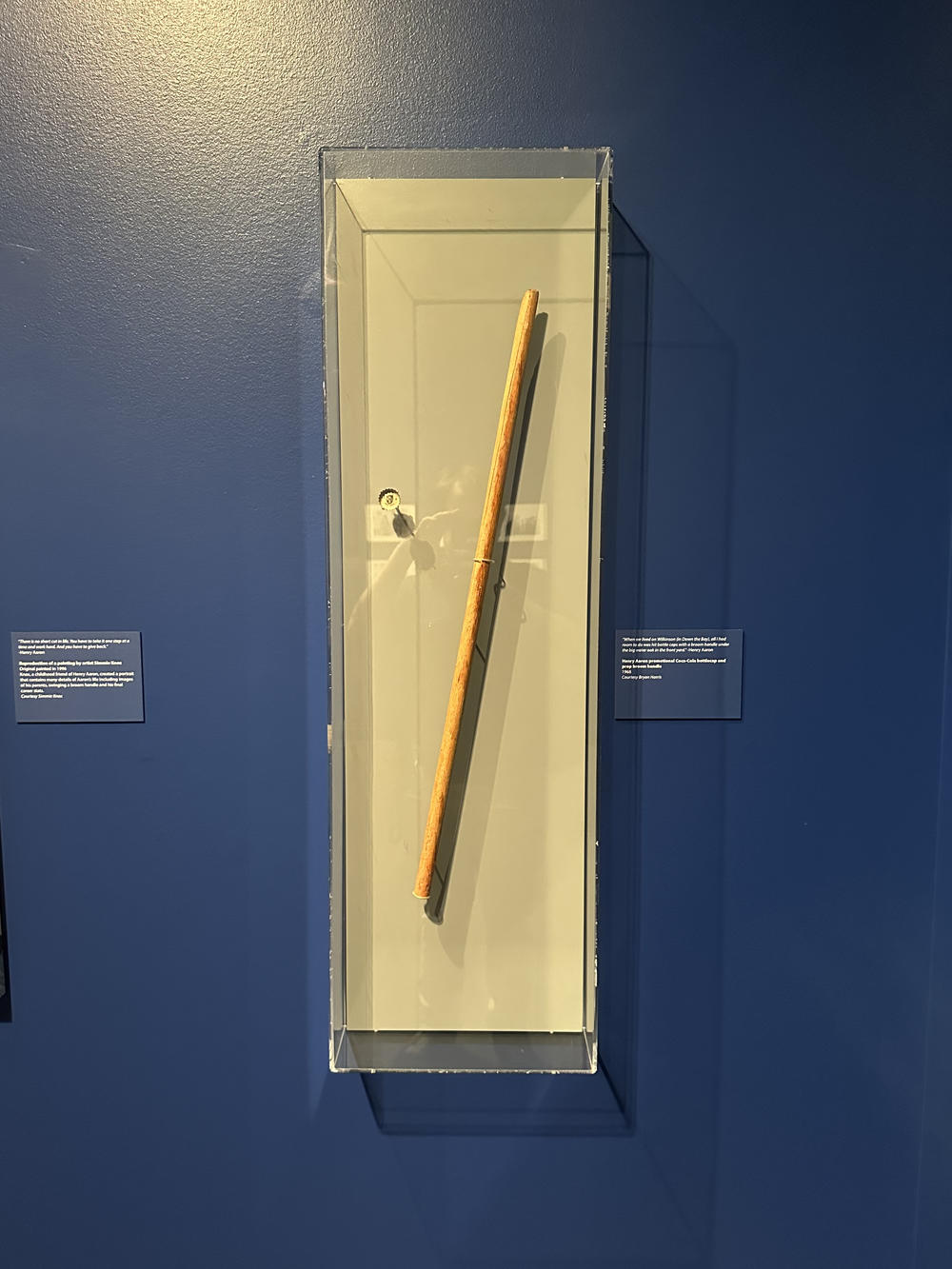

That same year, down in Mobile, Alabama, in a neighborhood called Down the Bay, a couple of Black kids named Tom and Henry turned thirteen years old. They loved baseball so much they would play the game even when they didn’t have a ball or a bat.

Tom and Henry would gather discarded Coke-bottle caps and imagine they were baseballs. They’d use a stick or an old broom handle as a bat.

Tom still lives in Down the Bay. He is eighty-nine years old today, but he remembers playing ball with bottle caps and broomsticks like it was yesterday.

Tom Weathers: They used to take them tops and make them curve… So you got to have a good eye to hit it, you know?

Chuck Reece: On certain Sundays, Tom and Henry and some other kids could scare up a real ball and bat. And they would gather with other kids to play ball. Sometimes even with white kids—at least until the cops broke up their games. Those were the days of Jim Crow, you see.

Tom Weathers: The white kids would come out, and we all played together. Soon as the police come, they break it up. Soon as they leave…we get back to it again. We had fun, you know. Yeah. We get right back to it.

Chuck Reece: Tom and Henry stayed friends their whole lives. But Henry passed away a few years ago.

Tom Weathers: I miss him a whole lot, man. Every day.… We played ball together when I was coming up. He was coming up, and we used to play at the parks, you know? Every Sunday, they used to have baseball games. And Hank used to go out there and…he was the best hitter out of the whole team.

Chuck Reece: Tom Weathers remembers his friend so clearly.

As do millions of us. His friend’s full name was … Henry Louis Aaron. Hammerin’ Hank, the home run king.

Today, on Salvation South Deluxe, we’re diving into the life of the late, great Hank Aaron. When he died at age eighty-six, he left behind one of baseball’s greatest legacies.

But Hank Aaron didn’t just change baseball on the field. He changed it off the field, too.

And he didn’t just change baseball. Hank Aaron changed the South. Forever.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed, hoping to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

ACT ONE

Chuck Reece: Hank Aaron became the home run king of baseball over fifty years ago, on April eighth, nineteen-seventy four. By that time, I was playing Little League ball myself, and my dad and I were watching breathlessly that night. Just like millions of other people around the world. Hank came to the plate for his second at-bat of the game with the Braves one run down. He took a pitch from the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Al Downing, then, when the second one came, he hit a solo shot over the left-center-field wall in Atlanta Stadium.

It was his seven-hundred-and-fifteenth home run, breaking the New York Yankees’ Babe Ruth’s forty-year hold on the Major League career record.

Milo Hamilton (from 715th home run call): Here’s the pitch by Downing. Swinging. There’s a drive into left-center field. That ball is gonna be…outta here! It’s gone! It’s seven-fifteen! There’s a new home-run champion of all time! And it’s Henry Aaron! The fireworks are going!

Chuck Reece: Although Aaron’s career home-run record was broken thirty-one years later by Barry Bonds of the San Francisco Giants, Hank still holds three career batting records——almost a half-century after he retired from the game.

Most runs batted in: two-thousand two-hundred and ninety-seven.

Most total bases: six-thousand eight-hundred and fifty-six.

And most extra-base hits: one-thousand four-hundred and seventy-seven.

Hank put up those numbers across twenty-three seasons in the Majors—twelve with the Milwaukee Braves, then nine here in Georgia after the Braves moved to Atlanta in nineteen-sixty-six, then back to Milwaukee to play his final two seasons for the Brewers.

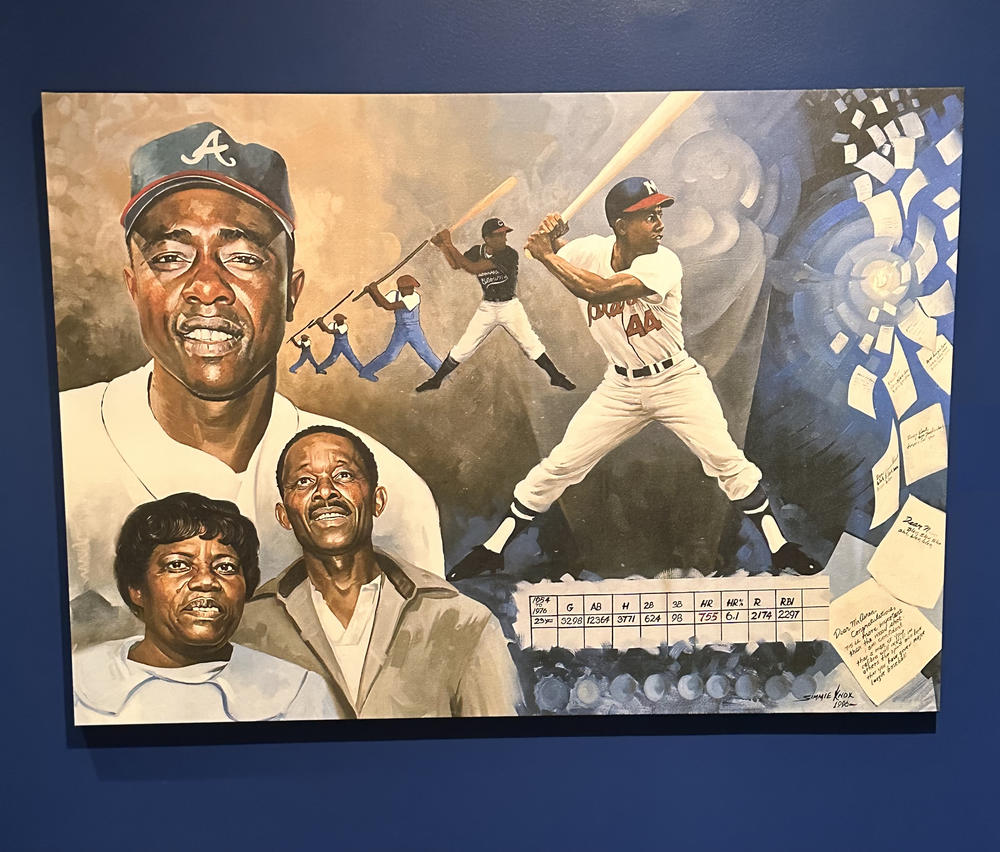

To commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the night in Atlanta when Hank Aaron became baseball’s home-run king, the Atlanta History Center opened an exhibition that brings not only that night to life, but also what happened in Aaron’s life before and after.

Paul Crater: My name is Paul Crater. I'm vice president of collections and research services at the Atlanta History Center.

“More Than Brave: The Life of Henry Aaron” is the life story of Henry Aaron, where we select highlights from his life to tell the story of his time growing up in Mobile to his time in the minor leagues, to his time with the Milwaukee Braves, the Atlanta Braves, and breaking the all time home run record in 1974, and him becoming an executive with the Atlanta Braves, and further making his mark—and making his mark just as a great human being.

Chuck Reece: Crater and colleagues at the History Center deserve praise for how they have designed “More Than Brave” to establish a central truth—that Hank Aaron’s life was far more than just a baseball story. That his heroism extended far beyond the ballfield. That his life—before, during, and after his two decades in the Majors—proved that Black Southerners could achieve infinitely more than the Southern white supremacists of the Jim Crow era could ever imagine. Or ever wanted to.

But to understand that story fully, you gotta start in the beginning, in the nineteen-thirties and forties, when Hank was just a kid.

One of the first things that catches your eye when you walk into the exhibition is a framed wooden box that contains a rusted bottle cap and a broomstick.

Paul Crater: That's kind of a symbol of how he grew up. You know, learning. Learning the game. Hitting a bottle cap with a broom handle is not the easiest thing in the world to do athletically. And so, you know, he really develops a skill and a love for the game and a confidence, you know, in himself. As a baseball player.

Chuck Reece: Hitting bottle caps with sticks speaks to the poverty kids like Hank Aaron and Tom Weathers grew up in.

Paul Crater: He grew up in Mobile, Alabama, you know, a Jim Crow City. …You know, his family were poor, working class people. His father worked in the sawmill. You know, he worked on the shipyards.

Chuck Reece: The pickup games that Tom Weathers remembers happened in Carver Park, which in nineteen-eighty-nine got a new name: Hank Aaron Park. Baseball mattered more than anything to the kids in Down the Bay. Tom Weathers told us there was something special about the neighborhood he and Hank grew up in.

Tom Weathers: There was something in the water down in Mobile.

Chuck Reece: One of the greatest Black stars in the history of baseball, the pitcher Satchel Paige, grew up there. Paige went pro in the Negro Leagues eight years before Hank and Tom were born. He finally joined the Major Leagues in nineteen-forty-eight. Down the Bay gave birth to another baseball legend, Willie McCovey. Five years younger than Aaron, McCovey played twenty-two seasons in the big leagues and hit five-hundred-and-twenty-one homers himself.

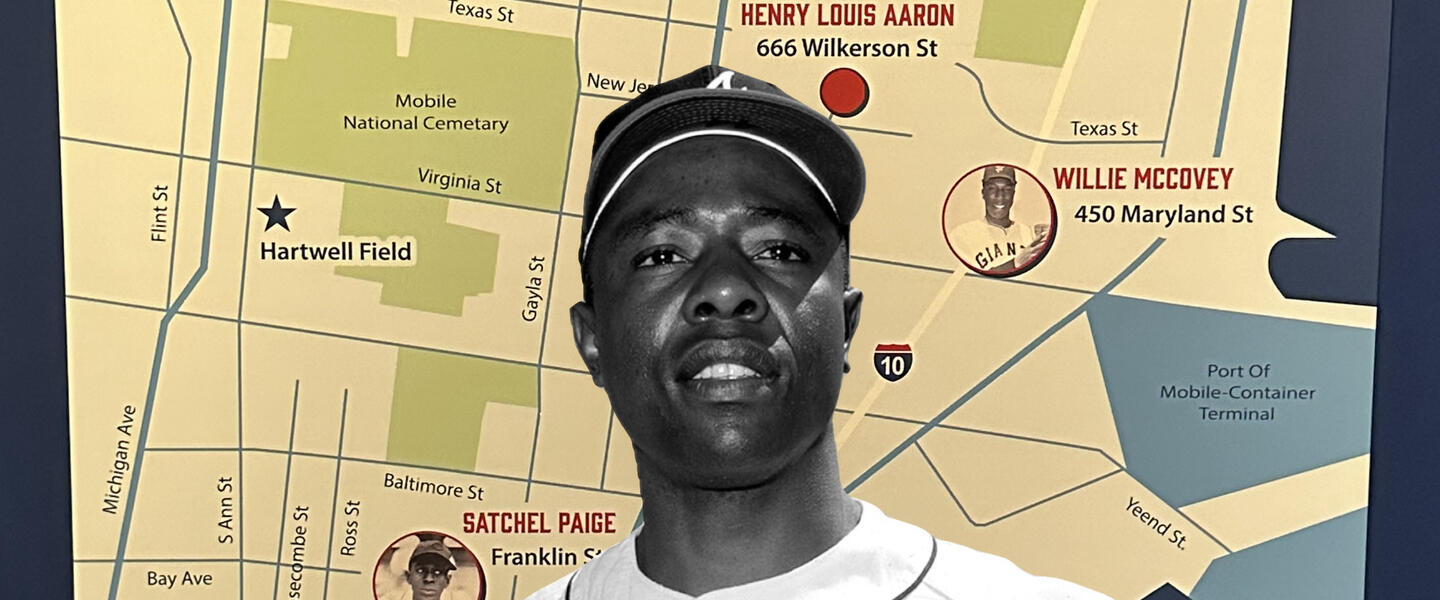

Paul Crater: Baseball, when Henry Aaron was growing up in the thirties and forties, was America's most popular sport. And, you know, there were lots of…there was a minor league team in Mobile. There were Negro League teams who came through Mobile. But more than anything, there was great talent that kind of grew up here. And this. Kind of illustrates that this is the map of the neighborhood known as down the Bay where Henry grew up. And so you had Henry growing up here. You had Willie McCovey growing up here. You had Satchel Paige growing up here in this little area. So in this…small area, this huge concentration of world class baseball talent was coming up…

Mobile is very unique, especially among African American players…a fertile ground for baseball talent.

Chuck Reece: Growing up, Hank Aaron idolized Satchel Paige and Jackie Robinson. Aaron was fourteen years old when Robinson broke the Major League racial barrier.

Paul Crater: Being able to play in the major leagues, all this kind of seemed possible to him because when he was fourteen, in nineteen-forty-eight…he saw Jackie Robinson in Mobile.… Jackie Robinson comes to, you know, a school in Mobile. He hears him speak. Skips school to hear him speak. And it's like. “I could do that. I could, I could, I could be a star. I could be a baseball player. I could play in the Major Leagues because Jackie's in the Major Leagues.”

Chuck Reece: Hank Aaron realized baseball could be his ticket out—not just out of poverty, but out of the Jim Crow South. He was only eighteen years old when he signed a contract with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues. But Major League teams were already scouting him. Particularly the New York Giants and the Boston Braves, who were just about to move to Milwaukee.

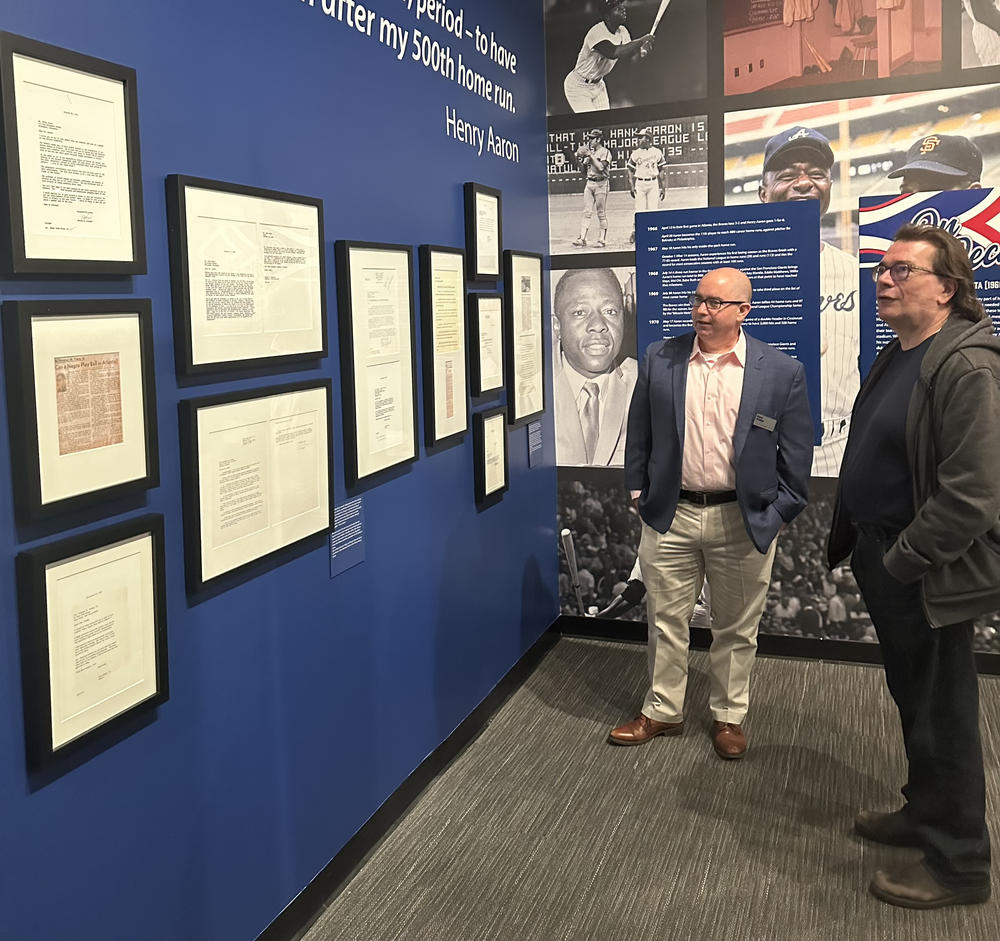

Several scouting reports on Aaron by different teams are framed and hang on the wall in the History Center. A particular one from a Braves scout is a hoot.

Chuck Reece (from "More Than Brave" walk through): July 1952 scouting report by Billy Southworth of the Braves organization. And he is rated, as a good hitter, a fast runner, a good fielder with a strong arm and a good attitude. But his power ranking is only fair. That's hilarious.

Paul Crater: You're seeing in the scouting reports that the scouts are saying this is an obvious prospect. There's no hint whatsoever that there's they're writing about, reporting about a guy who would basically could be on the Mount Rushmore of organized baseball. Right?

Chuck Reece: Crater points to a framed telegram on the wall.

Paul Crater: This is an interesting telegram. It's between John Mullin, with the Boston Braves, to Sid Pollock, the general manager of the Indianapolis Clowns. And it's indicating at what salary they would sign Henry Aaron to with the Braves. $350. Right. So there was a kind of a bidding war for Henry Aaron. One of the candidates was the New York Giants, who bid 300.

Chuck Reece (from More Than Brave walk through): Three-hundred dollars…

Paul Crater: And if they bid a little bit more, they could have had Henry Aaron and Willie Mays in their outfield. Wow.

Chuck Reece: A few years later, Willie McCovey joined the Giants. Aaron, Mays, and McCovey would have been the greatest outfield lineup of all time, but it was not to be.

Because Hank Aaron took the extra fifty bucks a week. To a kid who grew with next to nothing, that was big money.

Hank Aaron got something else when he signed that contract. A ticket out of the South. His next stop would be Wisconsin, where he would join one of the Braves’ minor league teams, the Eau Claire Bears.

After Aaron’s first season in Eau Claire, he traveled to Puerto Rico to play on a winter-league team, where he first met Felix Mantilla, up-and-coming Puerto Rican player in the Braves organization . When it was time to return north for the nineteen-fifty-three season, the Braves promoted Aaron and Mantilla to the Jacksonville Braves, a Class A team in Florida, and they were joined there by a third Black player, the journeyman outfielder Horace Garner.

Six years earlier, Jackie Robinson had broken the Major League color line. But in the South Atlantic League, where the Jacksonville Braves played, Jim Crow was still on the ballfield. The Sally League, as the South Atlantic is still known, had only eight teams back then. Jacksonville, plus four in Georgia—Augusta, Columbus, Macon, and Savannah. One in Charlotte, North Carolina. One in Columbia, South Carolina. And one in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Since the Sally League’s founding in nineteen-oh-four, not one team picture ever included a Black face.

Until Hank Aaron, Felix Mantilla, and Horace Garner.

The racist reactions came swiftly. Aaron and Mantilla faced verbal abuse, threats, and even physical violence. Not just from white fans but from opposing players and sometimes, even from teammates.

In the “More Than Brave” exhibition at the Atlanta History Center, an excerpt from Aaron’s autobiography, If I Had a Hammer, is printed on the wall.

Chuck Reece (from More Than Brave walk through): "People would send us letters saying things like they were going to sit in the right field stand with a rifle and shoot us during the game on a certain night. Felix got one in Jacksonville that said, ’N-word, if you play tonight, they're going to carry you away in a casket.’”

Here’s Paul Crater again.

Paul Crater: This section here begins to illustrate why the title is “More Than Brave.” What is, what was brave about Henry Aaron? Well, it's brave because, you know, he leaves home at age 18, never leaving Mobile before he goes to Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Never stepped on a field with white players before. … But then he goes to Jacksonville. And it's the Sally League, which was one of the most notoriously racist leagues in organized baseball. He integrates the Sally league.

They were getting threats all the time when they were in Jacksonville. So they had to live under racist Jim Crow practices.

Chuck Reece: Throughout the remaining twenty-three seasons of his career as a player, Hank Aaron never stopped getting threats[SM6] . When he ended the nineteen-seventy-three season only one homer away from tying Babe Ruth’s record, the flood of hate mail grew stronger than it had ever been.

Aaron never threw away those hateful letters. He would carry them throughout his life, along with the scars they left him with.

Salvation South Deluxe will be back right after this break.

ACT TWO

Chuck Reece: The constant barrage of racism did scar Hank Aaron, and his scars never healed.

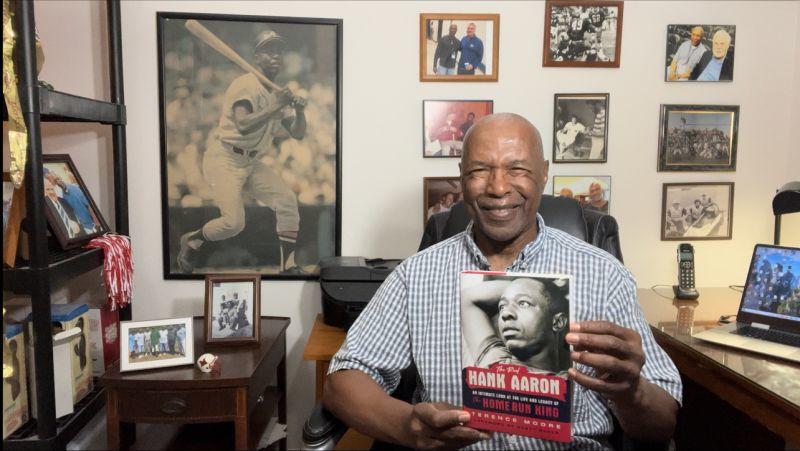

This is Terence Moore, a sports journalist who later became a very close friend of Hank and his wife, Billye. So close, in fact, the Aaron family asked him to serve as an honorary pallbearer at Hank’s funeral.

Terence Moore: The hate mail, the death threats and all that sort of thing…that never left Hank. Hank was traumatized by that for the rest of his life in so many different ways.

Chuck Reece: The trauma was great. So great, in fact, that when the Milwaukee Braves announced they would move to Atlanta for the nineteen-sixty-six season, thus becoming the first Major League Baseball team in the Deep South, Aaron was very reluctant to move with the team.

This is Sheffield Hale, a lifelong Atlantan and the president and CEO of the Atlanta History Center.

Sheffield Hale: Hank Aaron had serious reservations about coming to Atlanta. … A part of the exhibit is to show the letters that were sent to him…from HBCU presidents, from, you know, other influential black people in Atlanta…saying, oh, Atlanta's a great place. You need to come here.

Chuck Reece: It’s not hard to imagine why Aaron was reluctant. The clash over civil rights between Southern Blacks and whites was raging full-on.

During his last three seasons in Milwaukee, he had watched some of the American Civil Rights Movement’s most critical moments. Nineteen-sixty-three saw the capital city of Hank’s home state explode, when the Birmingham government used fire hoses and attack dogs to disperse Black civil-rights marchers, including more than a thousand teenagers and children. And later that year, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the historic 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four little girls—Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carol Denise McNair.

Nineteen-sixty-four brought the passage of the Civil Rights Act, and sixty-five the Voting Rights Act. When Aaron first took the field at the brand-new Atlanta Stadium, Black voters, finally freed from literacy tests and poll taxes, were registering by the hundreds of thousands. And Lester Maddox, an Atlanta restaurateur known for chasing Black customers away with a pick handle, was on his way to becoming Georgia’s governor.

When Hank Aaron arrived in Atlanta for the nineteen-sixty-six season, he could have chosen to keep his guard up and just play ball. But he knew that But his stardom had given him power, and he resolved to use it to support the cause of civil rights. For Aaron, this didn’t mean taking to the streets. It meant negotiating directly with Atlanta’s power structure, which now included powerful Black businessmen like construction magnate Herman Russell.

Here’s Sheffield Hale.

Sheffield Hale: He was highly connected with all those leaders, you know, the Russell family and people like that that were, in the Black community, very influential. You know, I think a lot of his influence was quiet and in the background because he was so public in terms of his what he was doing on the field. But he was very supportive of all of the, you know, the civil rights activities and Mayor Jackson and all of those people that were rising as Atlanta was changing, as the Black community was being more incorporated into the business community and obviously the political community of Atlanta.

He was that, you know, quiet presence. But he was he was there and supportive in…many ways, and many ways we probably will never know.

Chuck Reece: Hank’s hero, Jackie Robinson, died suddenly of a heart attack in nineteen-seventy-two. And his passing pushed Aaron to speak and act a little more loudly.

Here’s Terence again.

Terence Moore: One of the things that really gets underrated when it comes to Hank Aaron is how important he was to the civil rights movement. And I'm talking about even beyond just being an athlete.

Jackie Robinson was Hank Aaron's idol. For people who may not know, Jackie Robinson was very active. I mean, he used to march with Doctor King. … He was involved in politics, both Republican and Democratic politics.

Chuck Reece: Baseball’s biggest Black stars—people like Willie Mays and Chicago Cubs pitcher Ernie Banks—were not necessarily eager to fill Robinson’s shoes as a leader of the cause. Terence Moore recalls a story Hank told him about Robinson’s funeral.

Terence Moore: After the funeral, Hank goes up to Willie Mays and Ernie Banks and says, now that Jackie has died, it is up to us to take over Jackie's causes. And Hank tells this story to me. He says that both Ernie Banks and Willie Mays said, we're not going to get involved with that. They just basically just blew him off.

And this tells you everything you need to know about Hank Aaron. Hank Aaron said he didn't get mad. He didn't try to talk him into it. He said, you know what? I'll just do it myself.

And you see that track from 1972 right to his death wherein Hank Aaron became very active.

Chuck Reece: Aaron spent his final seasons on the field as an immaculate role model for Black kids who dreamed of making the Big Leagues, just as he had envisioned three decades earlier.

And there is a strong argument that Aaron set examples that were even more important after he left the field for the front office.

Terence Moore says Aaron’s biggest impact on the civil rights of African Americans—and the opportunities they had in American society—came after he laid down his bat and became an executive.

Terence Moore: When he became an executive in major league baseball, He was for the longest stretch the only African-American executive in baseball for years.

Chuck Reece: And during those years, Aaron battled not only racist threats from the public, but also within the ranks of Major League Baseball.

Terence Moore: He was receiving all sorts of hate letters and correspondence for being an outspoken Negro. Okay, I'm using that term lightly. I mean, he was still catching it, and a lot of the problems he was catching, too, were incoming not only from outside the baseball organization, but within the Braves organization.

Chuck Reece: Hank’s top priority when he became a front-office executive was to improve opportunities for Black ballplayers, coaches, and scouts, who were underrepresented in pro baseball. He did not like the fact that he was the only Black executive in Major League ball.

Terence Moore: Back in 1982, when I worked for the San Francisco Examiner… I was working on this series on Blacks in baseball because it was very apparent—in ’82, mind you, way back then—that there was something going on with African-Americans, where they were decreasing in numbers. And I just started doing this research, and I started finding out from talking to various people in baseball—players, management people, Black, white, and what have you—that there was a quota system in Major League Baseball to downsize the number of African-American players. Very explosive story.

The only black executive in baseball was Hank Aaron with the Atlanta Braves. I figured, hey, I got to call Hank Aaron and get him to comment on that. And almost instantly we connected, right off the bat.

Chuck Reece: When Moore joined the Atlanta Journal-Constitution two years later, he kept covering the story—and Aaron’s work to put more Black executives into baseball’s front offices and coaches on the fields.

As their relationship grew from journalist and source to friendship, Moore watched Aaron display two remarkable traits. The first was an uncanny ability to recruit the right players.

Terence Moore: One of the things that gets overlooked in history is how much Hank Aaron contributed to that record streak of 14 consecutive division titles for the Braves that started in 1991. And I want to tell you, that was a pet peeve of his, that he wasn't getting enough credit for that or any credit for that, because when people think about that streak, they primarily think of a couple guys, John Schuerholz and Bobby Cox, John Schuerholz, of course, being the general manager, Bobby Cox, the manager.… But the farm director during the ’80s, during the time when this talent was being built up, that was Hank Aaron.

Chuck Reece: Hank became known as a masterful recruiter for sure. But the more important trait he displayed was his humility and grace. The way he treated young players with respect. Really, the way he treated everyone with respect.

He was a legend, but he never acted the way you’d expect a superstar to act. He was never, in any way, a braggart.

But his work has changed Black lives for the better for thirty years now. In 1994, Hank and Billye Aaron established the Chasing the Dream Foundation. Its initial goal was to establish seven-hundred-and-fifty-five college scholarships—one for each of his home runs. They would go to deserving young people who didn’t have the money to attend.

The total number long since passed a thousand, and the foundation’s work now extends nationwide. The Chasing the Dream foundation now works in partnership with the Boys & Girls Clubs of America to find deserving candidates for scholarships. And the Henry Aaron Fellowships program helps develop the next generation of diverse business leaders.

And Hank did all of this with a humility that is too uncommon among stars of his magnitude .

His childhood friend, Tom Weathers, says when Hank would come home to Mobile, he never flaunted his stardom.

Tom Weathers: If he'd come home, it wouldn't be a day he didn't come by the house. He'd go by mama's and daddy's and he'd call me and I'd go by and get him and we'd ride around. … Got a place across the bay. He liked seafood. We would go over there and eat. … He loved his mother. loved his family, you know

Here’s Terence Moore again.

Terence Moore: He was a guy that was relatable to people. He understood people. People understood him, and he was able to project that. And that goes back to his youth, growing up, and just the way he was raised by his parents. You know, his parents were very much like that: treat people the way that you would want to be treated. All those lessons he learned and he carried on for the rest of his life.

I've been covering professional athletes for 46 years on a professional basis, and he is the most down to earth, bigger than life, athlete personality I've ever met.

You know, a lot of guys you meet…superstar type of guys where they have this aura about them, sort of the untouchable thing, you know, unrelatable-type thing. Hank Aaron was very relatable. I mean, he could come in and, you know, just fit right into the conversation.

I knew Hank for nearly 40 years. There was never a time when I did not feel in total awe around this guy. Okay? But it wasn't because he was acting that way. It was because of who he was. And he did everything in his power to make you feel at ease, to say that, hey, I'm just Hank. I you know, I know what you're thinking. I know what you're feeling, but I'm looking at myself—not at the way you're looking at me.

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank Paul Crater, Tim Frilingos, Carter Jackson, Sheffield Hale, and the staff of the Atlanta History Center for their help and cooperation in producing this episode. If you’re in driving distance, you should visit this Institution, which does an amazing job of presenting the history of Atlanta and the history of the broader South.

I’d like to give special thanks to Terence Moore, who not only gave us his time and insights, but whose twenty-twenty-two biography, The Real Hank Aaron, proved an indispensable resource for this episode. If you’re a baseball fan, a student of the civil rights movement, or both, you need a copy of Moore’s book.

I must also thank Cynthia Tucker, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and contributor to Salvation South, the online magazine I edit. She lives in Mobile, Alabama, today, and she connected us with Tom Weathers. To hear Mr. Weathers share stories of his lifelong friendship with Hank Aaron was a rare and wondrous pleasure. We thank Mr. Weathers and his family for being so generous with their time.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find twenty-four-seven at SalvationSouth.com.

Our producer is Jake Cook, a multitalented fellow who also composed our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without wonderful people like GPB’s Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.