Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: The Original Rednecks - The Battle of Blair Mountain

Primary Content

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece talks with "Rednecks" author Taylor Brown and scholars Gabe Schwartzman and Lloyd Tomlinson. He learns the ugly truth behind the origin of the term 'redneck' -- a shocking story of warfare carried out against American citizens by none other than their own government, which has been suppressed for nearly a century.

TRANSCRIPT:

Chuck Reece: There is a word used to describe certain Southerners that is very familiar—but whose definition is frustratingly elusive.

Redneck.

Webster’s Unabridged defines “redneck” as, and I quote, “a white member of the Southern rural laboring class.”

Wikipedia says redneck is, and I quote, “a derogatory term mainly, but not exclusively, applied to white Americans perceived to be crass and unsophisticated, closely associated with rural whites of the Southern United States.”

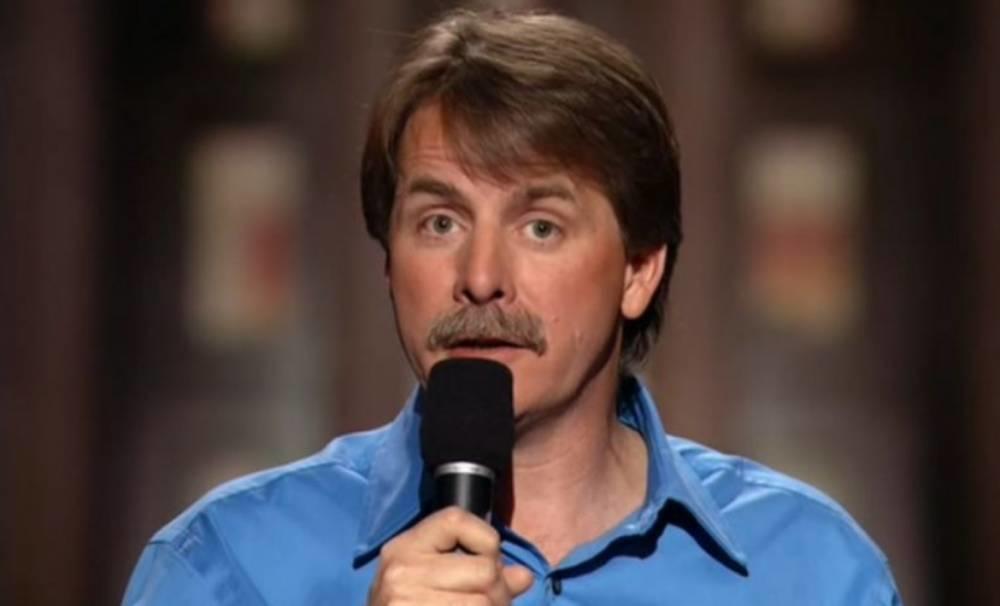

But those definitions fail to encompass everything the word “redneck” can imply. Thirty years ago, an Atlanta comedian named Jeff Foxworthy made millions of dollars defining the word in about a million different ways. Like this…

Jeff Foxworthy: If you own a home that’s mobile and fourteen cars that aren’t, you might be a redneck.

Chuck Reece: In fact, Foxworthy hit The New York Times Bestsellers list in two-thousand-and-six with a hundred-and-sixty-page book called “Jeff Foxworthy’s Redneck Dictionary.”

But Jeff never wrote a book on the origin of the word redneck. You’d figure he wouldn’t have to, because we all knew where the word came from—the sunburned necks of folks who had to work outside, in the hot sun, every single day.

And that was exactly what I thought. Until a writer named Taylor Brown taught me I was wrong about that.

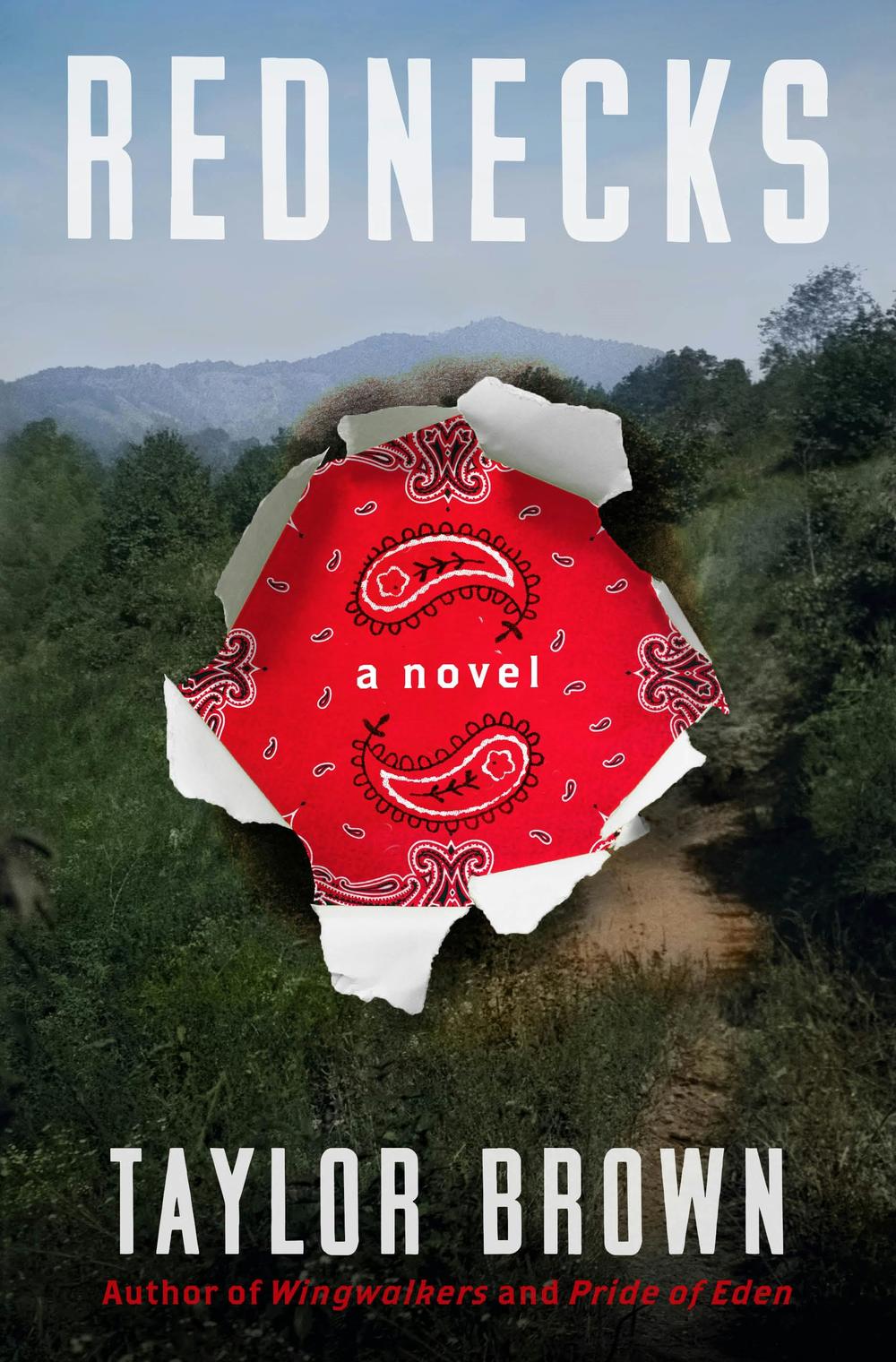

In late in twenty-seventeen, Taylor called to ask me if I would consider publishing a short story he had just finished. The story’s title was… “Rednecks.” And now, years later, that short story has grown into a novel with the same title.

Back then, Taylor told me about a conversation he had with another writer, his friend Jason Frye, who grew up in the high mountains of Logan County, West Virginia.

Taylor Brown: The book really started when we were…I was in his office one day and the word “redneck” came up and he said, you know where that word comes from, right? And I said what ninety-nine percent of people say, you know, sunburn on the back of the neck from working in the field.

And he was setting me up. You know, as soon as I said that, he kind of rubbed his hands together and got a spark in his eye and said, “Have I got a story for you.”

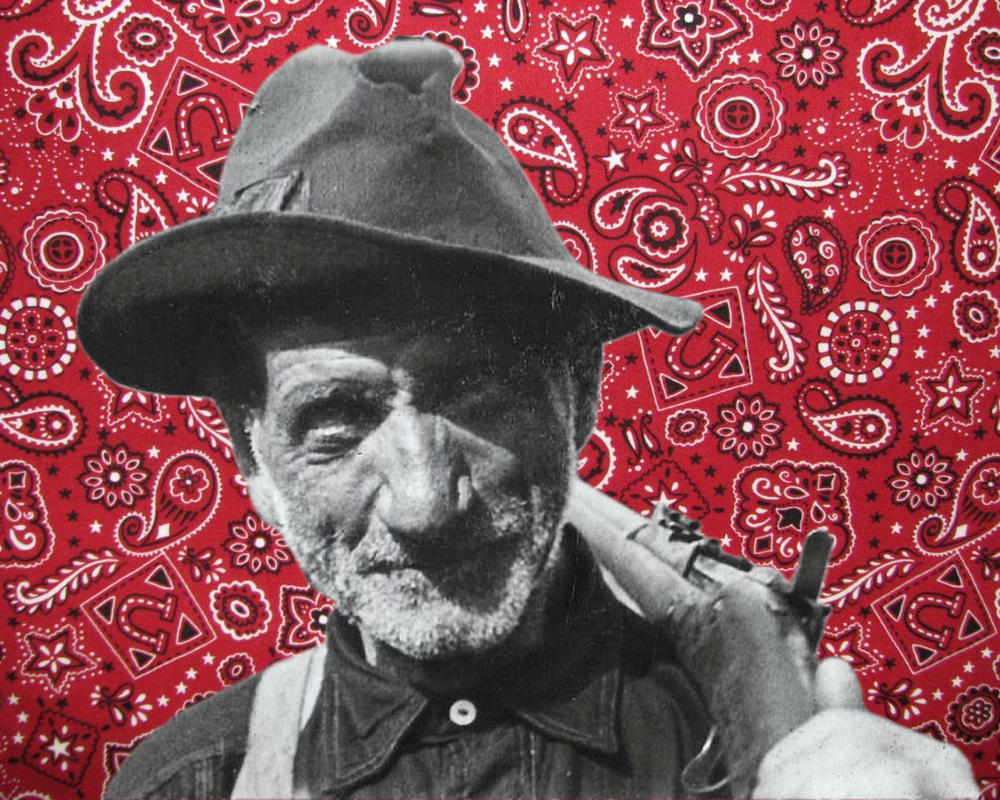

Chuck Reece: Taylor told me the same story Jason had told him—that the word “redneck” came from the red bandannas worn by the ten-thousand West Virginians who fought in the Battle of Blair Mountain.

The Battle of Blair Mountain. I had never heard of it.

I asked Taylor, “Was that a battle in the Civil War?”

“Nope, he said. “Happened in 1921.”

And that was when my eyes were opened to another part of Southern history that had been hidden from me. Something meaningful and monumental that, like our region’s history of slavery, powerful people had tried to erase from our schoolbooks.

Here are the basics:

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest armed conflict ever on American soil, apart from the Civil War. It was the largest labor uprising in American history.

On one side were over ten thousand West Virginia coal miners who went on strike against the coal companies that employed them. These bandanna-wearing rednecks were a wildly diverse group of white Americans, African Americans, and more recent immigrants to America from southern and eastern Europe.

On the other side was…well…the law. Local police from communities in the West Virginia coalfields. Coal company security guards. Armed private detectives hired to be strikebreakers, to put down any miners—violently, if necessary—who dared to talk about forming a union.

And in the heat of the Battle of Blair Mountain, the coal companies got some extra manpower: the armed forces of the United States of America. As far-fetched as it seems, American men freshly home from World War One were sent to fight their countrymen on American soil.

On September fifth, nineteen-twenty-one, a huge headline sat atop the front page of The New York Times:

FIGHTING CONTINUES IN MOUNTAINS AS FEDERAL TROOPS REACH MINES; PLANES REPORTED BOMBING MINERS

If you have never, until now, heard of the Battle of Blair Mountain—when armed U.S. troops were sent to fight…yes…rednecks—well, have we got a story for you…

I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth episodes that we add to our regular podcast feed. We try to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

Chuck Reece: Taylor Brown’s novel, “Rednecks,” is historical fiction, set in nineteen-twenty-one. Its narrative focuses on fictional characters—a small group of miners and their families, plus a Lebanese immigrant doctor. The character is modeled after Taylor’s own great-grandfather. In the book, his name is Domit Muhanna—or “Doc Moo,” as he’s called by the townspeople of Matewan, West Virginia.

But apart from those fictional characters, the novel hews strictly to the genuine history of the Battle of Blair Mountain and the events that led up to it. In Taylor’s book, along with dialog between his invented characters, you also find the actual words of historical figures like Mother Jones, the legendary activist in the labor movement.

Taylor’s six years of historical research seem to have allowed him, in “Rednecks,” to write movingly and insightfully about the conditions in which West Virginia miners worked a century ago. The words seem to come from inside the miners’ heads.

Here’s Taylor reading the passage that describes life in the mines:

Taylor Brown: All breathe a black dust, explosive, which swirls through the cramped, yellowy light. The pickers and shovelers work with red bandanas knotted over their faces, the cotton black-fogged over their noses and mouths.

Perhaps it's an inadvertent spark from a miner's pick, striking an unseen shard of flint. Perhaps a pocket of methane has just been exhaled from the strata, freed after eons. The mountain erupts. A train of fire bores through the tunnels and shafts and rooms. Men are burned alive, boys buried underground. A great plume of ash blows from the mouth of the mine and rolls skyward, seen for miles.

The morning papers will read: 21 KILLED IN MINE BLAST. The country will hardly register the news. Such headlines are frequent, far removed from the reading public, like earthquakes or eruptions on far sides of the world.

“Told you she’d blow, ain’t I? This wouldn’t never happen at no Union mine. We'd have them vent shafts we asked for.

The other miner looks over his shoulder, as wild as if the devil might be standing behind them, marking their words. He hisses through his teeth. “Hush with that talk, man. You're like to get us kilt.”

Chuck Reece: That was the world of the rednecks of Blair Mountain—men and boys alike working in back-breaking conditions. Deep underground, where one false move could trigger an explosion. And they hoped that the union-the United Mine Workers of America union, which was just thirty years old at the time-could deliver them from some of the danger. But they were deathly afraid that putting such hope into words, and speaking them aloud, could bring the guns of coal-company enforcers down on their heads.

Taylor Brown’s novel works so well because it is deeply grounded in the truths of Appalachian coal mining of the early twentieth century. To understand the Battle of Blair Mountain, and what it can teach us today, you must understand those truths.

And the first thing to understand is that all these rednecks were not white.

Here’s Taylor.

Taylor Brown: We think of rednecks, we think of white folks, right? But…you know, by 1900, in West Virginia, one in five miners was Black, one third were foreign-born. You had Italians, poles, Sicilians, Hungarians, Spanish, all these folks, and they're all living and working together. I mean, you look at old photos from this era, and all these folks are working right next to each other, and you don't expect to see that. Not only that, they're living next to each other.

Chuck Reece: The miners in the Tug River Valley, surrounding Blair Mountain, lived in communities called “coal camps,” built and owned by the coal companies. The companies owned the houses the miners lived in, the schools their children attended, and the churches where they worshipped.

They also owned the stores where miners and their families shopped for food and clothing. The miners did not get paid real U.S. dollars. Instead, they were paid in something called “coal scrip,” which could be spent only in company-owned stores, where the prices were always higher than the regular stores in towns like Matewan, the Mingo County seat.

This is Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson, a historian and the education director of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan.

Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson: If you're paid in company scrip, that means that you can't send money home to any family that you may have in the South or overseas. That means that you can't save up to buy a home of your own. You can’t save up to start a business of your own. And it creates that cycle of debt and this cycle of dependency that really did entrap a lot of these miners.

Chuck Reece: Ever hear that old coal miner’s folk song, “Sixteen Tons”? Remember the last line of the chorus? “Saint Peter, don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go. I owe my soul to the company store?” Now you know why Merle Travis wrote that line.

And the kind of conditions Taylor Brown describes in the opening of his novel? He did not exaggerate for dramatic purposes.

Taylor Brown: You know, working in a coal mine in West Virginia in this era was statistically more dangerous than serving in the military in World War I, which is just mind-blowing.

Chuck Reece: Many of the rednecks had, in fact, fought for the United States in that war—even though they did not have to.

Taylor Brown: Coal miners were exempted from the draft in the Great War, World War I, because the country needed coal to run everything, especially a war. But they volunteered anyway in droves. I think West Virginia had the highest per capita volunteer rate of any state in the Union. So they go over there and serve their country…save democracy in Europe and from the Kaiser and all that kind of stuff.… But they come home and they're treated even worse than they were before they left.

Chuck Reece: Their hopes—for new technology that could lower the risks inside the mine, for the chance to earn real money so they could shop where they wanted to and live where they wanted to—rested with the United Mine Workers of America. The UMWA organized miners in the Midwest, and had become the first labor union formally recognized by the U.S. Government.

But the coal companies in West Virginia were determined to keep the union from duplicating those successes. So they hired an outfit called the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency as a private security force. The armed Baldwin-Felts agents suppressed union activity at every turn. If you were a miner and the Baldwin agents heard you had joined the union, they would get you fired and turn up to throw you and your family out of your company-owned house at gunpoint.

In the summer of nineteen-twenty-one, an increasing number of miners committed to the union. And as soon as they did, the Baldwins evicted them and their families. The miners moved into tent camps, which quickly became overcrowded, muddy, and squalid.

And the longer they stayed there, the angrier they got, and the more determined to fight they became.

Salvation South Deluxe will be back right after this break.

Chuck Reece: Many of the evicted miners living in those tents were World War One veterans. They knew how to be an army, so they organized themselves like one. On August twenty-fifth, thousands of miners tied their red bandannas around their necks—so they could recognize each other in the steep, heavily wooded terrain—and marched toward Blair Mountain.

Up on the mountain, Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin with his deputies, the Baldwin-Felts men and an armed “vigilance committee” had set up fortifications, armed with machine guns and bombs. Chafin even had private pilots drop bombs on the miners. For four days, the battle raged, until word came that U.S. President Warren G. Harding was sending foot soldiers and bombers.

The headline atop the front page of The Washington Times on September first read: AIR FLEET ORDERED TO WEST VIRGINIA BATTLEFIELD; AVIATORS WILL DROP BOMBS ON MARCHERS.

But the U.S. Army never fired a shot at the miners, and its planes dropped no bombs. Because when the word came, the miners knew they were beaten.

In his novel, Taylor Brown conjures up a commander of the redneck army delivering the news:

He’d been all across Blair Mountain in the night, hiking from unit to unit, speaking in trenches and foxholes, telling the men it was time to stand down, to go home. The U.S. Army had arrived. Their fight was with King Coal, not Uncle Sam. … They couldn’t fight the United States military. Most of the miners agreed, and word spread through the night. Time to pack up, to come down the mountain, to head home.

That week at the end of August, nineteen-twenty-one, had been one of the most dramatic in the history of our nation.

Although the Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest labor uprising in American history and the largest armed conflict on our land since the Civil War, it was not the only such war in the coalfields of Appalachia. This is Gabe Schwartzman, a University of Tennessee professor who studies politics and economics in Appalachia.

Dr. Gabe Schwartzman: One of the sites where the labor movement was really developed was in struggling for rights and working conditions and living conditions in coal towns in central Appalachia, and the Battle of Blair Mountain is a great example. What's wild is that the Battle of Blair Mountain is just one of a handful of armed labor conflicts of that period, right? In Tennessee, we have the Coal Creek War. In West Virginia, there was the Paint Creek andCabin Creek wars. Bloody Harlan happened in Kentucky. It's a whole bunch of those moments where people really rose up to challenge the conditions under which they were living.

Chuck Reece: The Coal Creek War Gabe mentions happened in eighteen-ninety-one, when the Tennessee Coal Mining Company fired its miners after a pay dispute and replaced them with convict labor. Throughout the teens, the twenties, and the thirties, the Baldwin-Felts agents—the “gun thugs,” sa the miners called them—were battling against coal miners. Nineteen-twelve and -thirteen brought the Paint Creek and Cabin Creek strikes in West Virginia—eight years before Blair Mountain. “Bloody Harlan” was a conflict in the nineteen-thirties with coal miners struggling to unionize in Harlan County, Kentucky.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt became president of the United States in nineteen-thirty-three, with the Great Depression in full effect. FDR supported the rights of workers to join labor unions and by 1935, he had signed into law the National Labor Relations Act.

But by the early nineteen-forties, the Battle of Blair Mountain had practically disappeared from the national dialogue. It was as if someone had waved a magic wand, and poof, it was gone.

Here, again, is Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson, the director of education at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan.

Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson: There were people who held enormous amounts of power within West Virginia that would prefer that this history be forgotten. Because it makes them look bad and it doesn’t really put stuff like the coal industry, or big business, or even capitalism in the best light.

Chuck Reece: Also in nineteen-thirty-five, FDR signed an executive order creating the Works Progress Administration. The WPA was a major part of Roosevelt’s New Deal program, and it put more than three million unemployed Americans to work in construction projects, paving roads, and building parks. Part of the WPA was something called the Federal Writers Project, which hired unemployed writers and editors. Some of American literature’s greatest names—Ralph Ellison, Saul Bellow, Zora Neale Hurston, John Cheever, and others—worked for the Writers Project.

Each state had its own Writers Project, assigned to research, write, publish a guidebook to that state. Starting in nineteen-thirty-eight, the West Virginia Writers Project was headed by a journalist named Bruce Crawford. Crawford had covered the plight of coal miners for years and championed their causes. He’d even been shot in nineteen-thirty-one in Harlan County, Kentucky.

And Crawford was determined that the West Virginia state guide would tell the story of the Battle of Blair Mountain.

Here’s Lloyd Tomlinson again.

Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson: The person writing the State Guide for West Virginia as part of the Federal Writers Project was a man named Bruce Crawford. I live in Norton, Virginia, and for about 10 or 15 years, he ran a pretty left wing newspaper for the time called Crawfords Weekly out of Norton. He was involved in the Harlan County strikes as well. But he's writing this state guide for West Virginia. And of course, Crawford being Crawford, he's going to talk about these labor issues and Mother Jones and the Battle of Blair Mountain. The entirety of the Mine Wars…

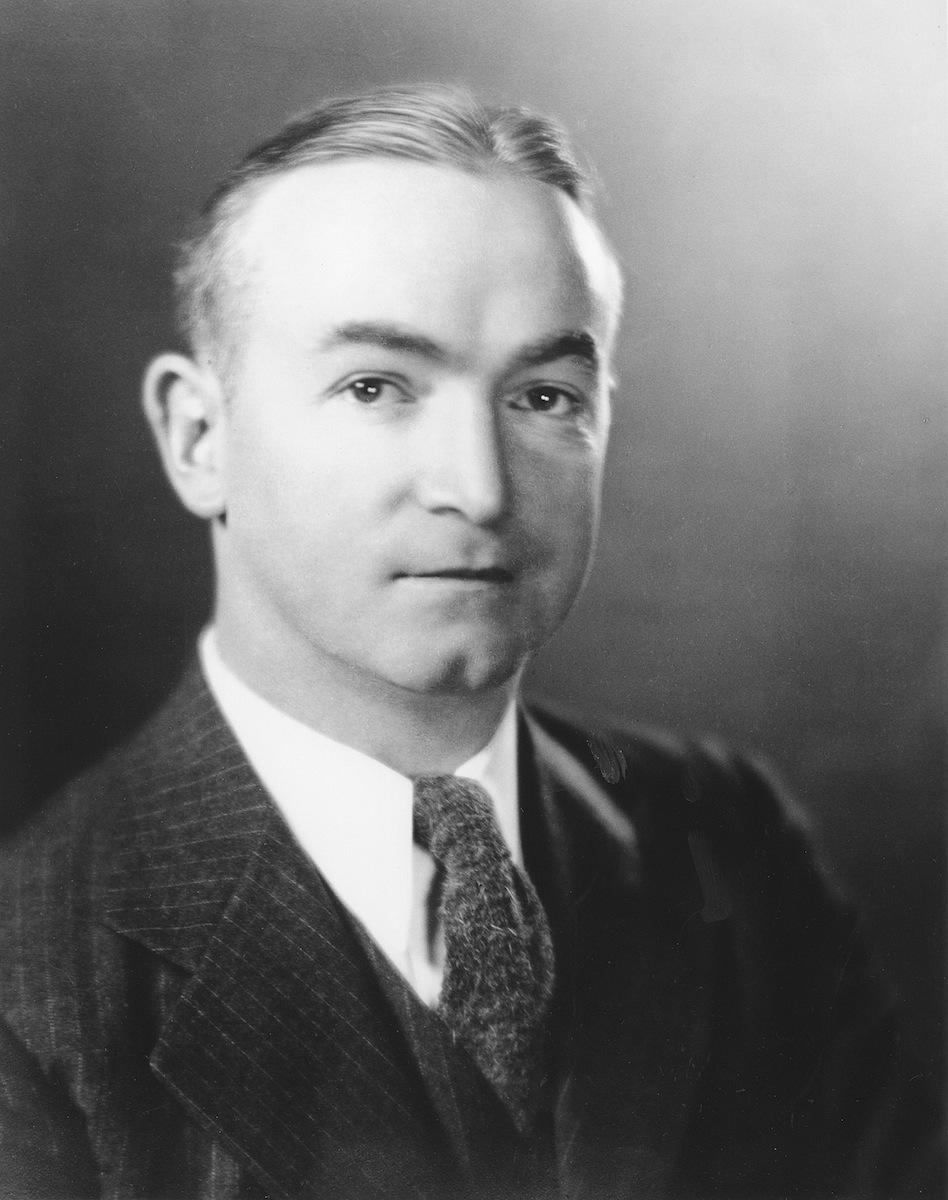

Chuck Reece: The governor of West Virginia, Homer Adams Holt, had other ideas.

In the collection of the Mine Wars Museum and in the West Virginia State Archive, there is a letter from Governor Holt’s secretary to an administrator at the Federal Writers Project in Washington.

Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson: It’s Holt’s secretary talking to one of the administrators of the Federal Writers Project, and it's this laundry list of complaints. If the mine wars were going to be mentioned at all, they, according to Holt, they didn't deserve more than two or three lines.

Chuck Reece: Just a few lines to cover more than a decade’s worth of armed conflict? Governor Holt had more complaints, too.

Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson: He complained that Mother Jones was mentioned at all. … And one of the most striking things about Holt's complaints…he vetoed a photograph of a Mexican coal miner. That was included in the book and he said that essentially—this is paraphrasing—but Mexican coal miners were few and far between and West Virginia is proud of its Anglo-Saxon heritage.

Chuck Reece: Proud of its Anglo-Saxon heritage… Hearing about that comment, I told Dr. Tomlinson it reminded me of the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s campaign to rewrite the history of the Civil War.

Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson: I can definitely see the connection there.… You have stuff like the Wilmington Race massacre. Tulsa. … Different atrocities that I didn't even learn about until I was pretty well into my college career. So it is this attempt to control the narrative.

Chuck Reece: “History is written by the victors,” someone once said. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly who said that. One version of it, however, is documented. It was originally spoken in German, but the English translation goes like this: “The victor will always be the judge, and the vanquished the accused.”

That was spoken during the Nuremberg Trials, in nineteen-forty-six, by Hermann Göring [GUR-ring], Adolph Hitler’s right-hand man.

But take heart, y’all. Truth can be added back to history. We see it happening all over the South—all over the nation, really—in countless efforts at racial reconciliation.

And you can see it at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan.

Dr. Tomlinson says the museum is the destination for many field trips for West Virginia students of all ages. I asked him what he hopes the students learn when they visit.

Dr. Lloyd Tomlinson: There's two really important things that I want students to remember when they come away from the museum. The first is that This is a people's history, and it is people's history that was suppressed for decades. And because of that, I want them to sort of understand the importance of telling these stories and preserving them and making sure that they're not lost to future generations. The other thing that I want them to remember is what the miners were fighting for. And ultimately, that is their civil and constitutional rights. They were fighting for things like freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, freedom to organize into labor unions, to fight injustice. And this is all stuff that we as Americans sometimes take for granted. … The fight to preserve those rights and to enjoy those rights is something that isn't in the distant past. This is something that people are still fighting for today. So I want them to be able to make those connections between what the miners were fighting for during the mine wars and broader civil rights struggles that continue on into the present.

Chuck Reece: Those are indeed good lessons.

We’d like to thank Taylor Brown for his help and cooperation in producing this episode. I cannot recommend his writing highly enough. In “Rednecks,” he has brought an important, overlooked piece of American history to vivid life. I’m proud I could publish, all those years ago, the story that contained the seeds of this book. I’d also like to thank our scholars, Doctors Lloyd Tomlinson and Gabe Schwartzman.

And I would encourage you to visit the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan, whose stated purpose is to—quote—“remember … past struggles even when people today are having to fight to keep rights won a century ago.” To plan your visit, go to double-U V Mine Wars dot org.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find twenty-four-seven at Salvation South dot com.

Jake Cook produces all episodes of the Salvation South Podcast, and he composed our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell. And all of us at Salvation South are grateful to the wonderful folks at GPB, most particularly Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

For more on this story:

West Virginia Mine Wars Museum

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece talks with "Rednecks" author Taylor Brown and scholars Gabe Schwartzman and Lloyd Tomlinson. He learns the ugly truth behind the origin of the term 'redneck', a shocking story of warfare carried out against American citizens by none other than their own government, which has been suppressed for nearly a century.