Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: The Telling and Twangy Tale of the Banjo

Primary Content

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece goes deep into the complicated history of the banjo, from its origin on the shores of the Carribean and West Africa to its rise as a ubiquitous icon of Southern "hillbilly" culture and beyond.

Chuck Reece: Twenty years ago, an archaeologist in Germany found the oldest known musical instrument on earth: a 35,000-year-old flute carved from ivory.

Human beings have been playing musical instruments since before we had written language. Which makes sense to me, because music, unlike languages, needs no translation. And any individual instrument can — theoretically — play any kind of music. Take the violin…

MUSIC: Adagio from Bach’s Violin Sonata No. 4 in C Minor, BWV107, Played by Itzhak Perlman

Chuck Reece: That’s the legendary Itzhak Perlman playing a violin sonata by Bach, written in the 1700s.

Then you can listen to this other music written about the same time…

MUSIC: Mark O’Connor - “Soldier’s Joy”

Chuck Reece: That’s an Appalachian fiddle tune called “Soldier’s Joy,” here played by Mark O’Connor.

Some people might believe classical violin belongs to high-dollar people, and some might believe mountain fiddle belongs to low-dollar folks. But no ever thinks the instrument itself can be played only by a certain class of players.

I think that for most of our lifetimes, only one instrument’s sound has struck fear and derision into certain people’s hearts.

The banjo.

MUSIC: “Dueling Banjos” from Deliverance

Chuck Reece: That particular song is called “Dueling Banjos,” and it was the theme of a movie called Deliverance. In that film, four businessmen from Atlanta take a weekend trip to paddle a river in the North Georgia mountains. Along the way, two criminal-minded mountain men assault them — in grievous, ghastly ways.

Jeff Mosier: And, you know, then the sticker came out: "Paddle faster. I hear a banjo." You know, those stickers came out…and I was like, "oh my God, please."

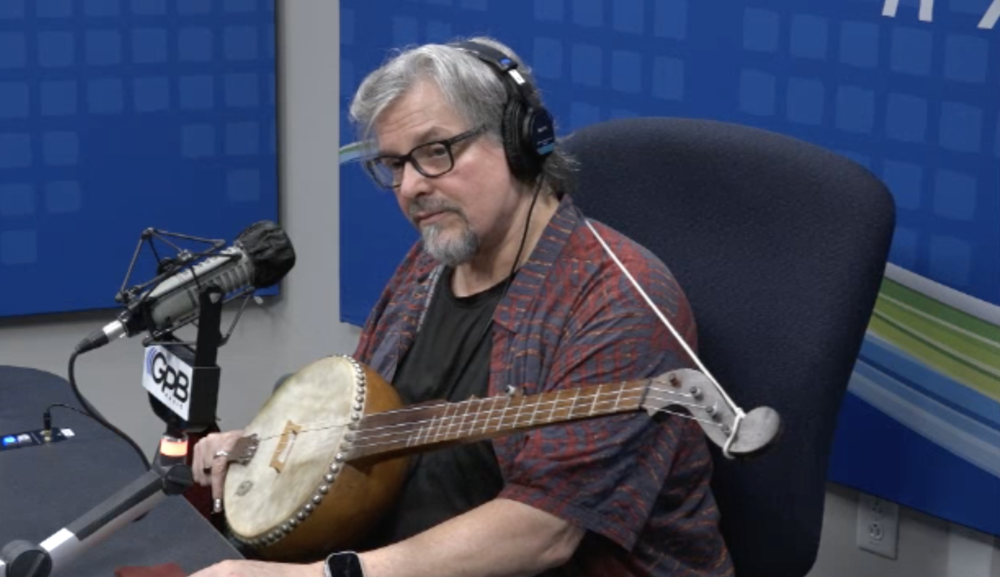

Chuck Reece: That is Jeff Mosier, who is something of a legend among banjo players. We’ll come back to Jeff in a minute.

But to his point about that “Paddle faster. I hear a banjo” bumper sticker, “Dueling Banjos” cemented the idea the sound of a banjo means you should look out for dangerous hillbillies. Ten years earlier…

MUSIC: Lester Flat & Earl Scruggs – “The Ballad of Jed Clampett”

Chuck Reece: …the theme song from a TV show called The Beverly Hillbillies had laid the groundwork for that.

For the last six decades, your average American citizen hears that instrument and thinks the sound is comical or foreboding or both.

They don’t hear the skill of Earl Scruggs, the groundbreaking North Carolina bluegrass picker who played that theme song.

They don’t hear the banjo strums that were part and parcel of the invention of jazz in 1920s.

MUSIC: Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five – “Gut Bucket Blues”

Chuck Reece: And they definitely do not hear the roots of the instrument, which reach all the way down through the Caribbean and across the Atlantic Ocean to West Africa.

Just like the okra that binds our gumbo, the banjo arrived with people who did not come here by choice, people who instead came here in shackles.

The story of the banjo is a uniquely Southern story, in which great joy arises from the deepest and darkest sort of pain. And if you don’t know that story, stick around. We’ve got some really special people here to tell it to you.

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed hoping to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

ACT ONE

Chuck Reece: Jeff Mosier is an Atlanta banjo player who took the instrument into whole new worlds with bands like Widespread Panic and Phish and the late great Colonel Bruce Hampton’s Aquarium Rescue Unit. If you’ve grooved to some banjo in one of their songs, Jeff is who you should thank.

Jeff Mosier: The first time I ever saw a banjo and connected with it, I was probably 5, sitting on my grandmother's lap in Tennessee, where I'm from. I'm from Bristol.

Chuck Reece (from interview): Oh, you're from Bristol.

Jeff Mosier: I am from Bristol.

Chuck Reece (from interview): The site of the big bang of country music.

Jeff Mosier: It is the birthplace, really. My grandmother was also a player, and her and her sister did the Maybelle Carter style guitar, and they were local, like little local heroes. They would play for the Madison shows and the caravans that would come through. They called them Gypsy caravans. And, so my grandmother had the gene for performing, and she would point out things on TV. "That’s this guy, that's that guy." And the first time she did that was Buck Trent on the banjo. He smiled, and he was doing this thing with his fingers that literally to me, as a child, look like, just — it looked like a optical illusion, like, how could his fingers be making all those notes? And so, that was really where I got it.

Chuck Reece: What hooked Jeff was the three-finger picking style, invented in the late '30s and early '40s by the aforementioned Earl Scruggs. Before he died, Earl Scruggs said the style came to him almost as if he was in a dream, that it was like he woke up playing it. And he could play it at blinding speeds.

We’ll let Jeff demonstrate it for you, more slowly.

Jeff Mosier: The Scruggs thing basically is an eight-count roll. And then you add the left. The left hand, which is a slide. You're just sliding your fingers on the string and then you can do hammer ons. Now add the hammer on with the slide and you got the .... Then there's a pull off and that's pulling off. So you just you're fretting a string and then pulling off of it. So slow, It sounds like this.

MUSIC: Jeff Mosier sings “Cripple Creek”

"I've got a gal and she loves me. She lives down in Tennessee…”

Chuck Reece: But it wasn’t until the late '80s, when Jeff first encountered the brilliant and absolutely unclassifiable Atlanta musician Bruce Hampton, that he learned the banjo was not the invention of white Appalachian musicians.

Jeff Mosier: Not until I met Colonel Bruce Hampton in 1988, who became my mentor and best friend — he told me that. The banjo was from Africa.

Chuck Reece: Okay, let’s stop right here and make something clear. The banjo — B-A-N-J-O — did not come to America in the hands of enslaved Africans. In the 1600s, as enslavers kidnapped people in West Africa and brought them to the American colonies, they of course could bring no possessions with them.

Still, they brought with them the knowledge of musical instruments like the akonting (uh-CON-ting). The akonting dates back centuries — before recorded history — to the Jola people of Senegal and Gambia in West Africa. And it’s clearly one of the banjo’s precursors.

Akontings are built by taking animal skins — typically goat skins — and stretching them tightly across gourds, which creates a resonator. A drum, essentially. Then a wooden or bamboo neck was attached to the gourd, and a bridge was attached to the goat skin. And strings made of animal ligaments were stretched from the bridge down the neck to a peg head.

This is Daniel Jatta, a Gambian musician and scholar, playing the akonting.

MUSIC: “Daniel Jatta Plays an Akonting Tune Written by his Father”

Chuck Reece: Now of course the slave trade in the colonies wasn’t limited to kidnapped Africans. Enslavers also kidnapped people in the Caribbean. They had similar instruments, and the word “banjo” probably derives from Caribbean instruments like the banza and the banjar. When Jeff came to visit us in the studio, he brought along a banza. Here’s what it sounds like.

MUSIC: Jeff Mosier plays the banza

Chuck Reece: Hannah Mayree is a California-based banjo player—and a student of banjo’s roots in Africa. She says that without understanding these predecessor instruments, she could never appreciate the culture and history bound up in the banjo she plays today.

Hannah Mayree: The banjo, you know, historically, it's always been a cultural piece not only for African-Americans but people across the diaspora ... because it is Earth based.

Chuck Reece: In instruments like the akonting and the banza, Hannah says, you can see the literal connections to the earth — the plants that yield the gourds and the animals whose skins are brought together to make the instrument resonate.

That connection to the Earth, Hannah says, allows us to come together in the same spirit that we come together around a common table.

Hannah Mayree: When you engage in this, you're also engaging in…creating a healthy ecosystem. You're engaging in creating food security in your community as well. There's a lot of different aspects that go just from the fact that this is an indigenous practice in the first place — that many people can engage just on that basis. We can come together around playing music, learning and exchanging, you know, tunes from different places. There is so many aspects of this, culturally, that are coming from the community and, in a lot of senses, stays in the community.

Chuck Reece: That spirit, that knowledge, Hannah says, came to these shores with her ancestors who were brought here in chains. Enslaved people took the knowledge of the akontings and banzas they had played when they were free and built their own instruments from materials they found on these shores.

Plantation owners had mixed reactions to this music coming from the people they enslaved. Some shut it down, but others tolerated or even encouraged it, figuring that if their slaves found pleasure in music, they might be less likely to revolt.

But the white enslavers never dreamed of playing the instrument themselves until after they forced their slaves to perform at parties and galas. Evidence suggests this began happening in the late 18th or early 19th century. And afterward, white people took up the banjo. Plantation ladies picked it up first.

Here’s Jeff Mosier again.

Jeff Mosier: You know, it became a parlor instrument. They made them for ladies — real long necks so the ladies would look pretty playing them. And they actually had notation and people would read music, and it was an uppity thing. You know, like white people playing in the parlor, you know, in the antebellum era.

Chuck Reece: After that, the banjo began to travel. In the middle of the 19th century, a New York City playwright by the name of Thomas Dartmouth Rice began to perform on the banjo —in blackface. The minstrel show was born, and it traveled across America and even internationally from about 1850 to 1870. Rice was particularly famous for a character named — have you guessed it yet? — Jim Crow.

Moving into the late 1800s, in the less urban environs of the Appalachian Mountains, Black and white people alike were playing the banjo. Even before the Civil War, there had been several communities of free people of color in the mountains. And after the United States Army defeated the Confederacy and slaves were emancipated, mountain string-band music flourished in Appalachia, and the music crossed racial lines.

Wayne Martin is the executive director of the North Carolina Arts Foundation, a musician and a musicologist. I talked to him about the history of the instrument in that era.

Wayne Martin: In almost every community in the South, there were African-American fiddle players and banjo players in the 19th century and early, early 20th century. That folk tradition is adapted into what we now know as fingerpicking and bluegrass.

Chuck Reece: Wayne told me a story about a conversation he had with someone who was writing a book about Carter and Ralph Stanley of Virginia — the Stanley Brothers, one of the pioneering groups in bluegrass. In the eyes of bluegrass and mountain musicians, Ralph Stanley and Earl Scruggs are considered the gold standards of banjo picking.

The writer, Wayne told me, was trying to draw a direct line between Ralph Stanley and the African American string bands of Appalachia.

Wayne Martin: I told him … I can't draw a straight line back … from Ralph Stanley to African American string bands. I mean, there was, you know, by the time Ralph Stanley was growing up, for all I know, the people in the county he grown up may have forced all the people of color out, because in the in the teens and ’20s, that happened a lot. ... I mean, Ralph Stanley may have not grown up with very many people of color around him. … There may not have been a Black string band in their neighborhood.

Chuck Reece: But is there evidence for musical crossover between Black and white banjo pickers in the mountains? Wayne told me that if you study the early-20th-century music of Appalachia, the evidence is inescapable.

But it wasn’t until early in this century that the Black history of the banjo began to get serious recognition across America and around the world.

One of the people who made that happen will be with us when Salvation South Deluxe returns after this short break.

ACT TWO

Chuck Reece: Welcome back to Salvation South Deluxe. I’m your host, Chuck Reece.

A minute ago, Wayne Martin told us there were many documented stories of Black banjo players in Appalachia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

If you’re curious to learn those stories, the first place you should look is in a book called African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia. It was published in 1995. A professor at Appalachian State University named Cecilia Conway wrote it. Professor Conway had scoured the mountains interviewing every elderly Black banjo picker she could find, documenting their songs and stories.

A few years later, an African American scholar from Connecticut named Tony Thomas started an internet mailing list called "Black Banjo Then & Now." On that list, a growing number of curious scholars and regular folks compared notes about banjo history.

In 2005, Thomas and Conway decided to throw a fish fry for their banjo nerd friends in Boone, N.C., the home of Appalachian State. They invited some friends, including Joe Thompson, an 87-year-old Black banjo player from North Carolina, whom Dr. Conway had interviewed. Also, a fellow named Sulé Greg Wilson, a musician, storyteller and shaman from Washington, D.C. Sulé, in turn, invited a young Black man from Phoenix, Ariz., by the name of Dom Flemons, who had fallen deeply under the spell of old American folk music. Dom often gathered with other young folk musicians to talk and perform in Phoenix’s Encanto Park.

Dom Flemons: When I started to play the banjo in around 2002, I had gotten an old banjo in a junk shop. ... I was approached by a fellow named Sulé Greg Wilson ... over at Encanto Park. … They used to have a Wednesday night folk night. And this was a place where I first really started doing a lot of performing. And one night, Sulé came in, and he and I got to talking, and he had heard about me … because I was a young African American man playing the banjo.

Chuck Reece: So Sulé invited Dom to come to that fish fry in North Carolina. He promised that if Dom could manage the plane fare, he would feed him and find him a place to sleep.

It turned out that 2005 gathering was far more than just a fish fry.

It would come to be known as the first Black Banjo Gathering. It was a watershed moment, and it changed Dom Flemons’s life.

Dom Flemons: When I went to the Black Banjo Gathering, amongst all the people I met at this, this, you know, decent-sized academic event on the history of the banjo, I was able to make connections with people that would allow me to make my way to North Carolina. Because basically, after I finished college, I figured I had nothing to lose, so I sold everything I owned, and then I jumped in my car and I just drove out east to North Carolina, and that was when I started the Carolina Chocolate Drops.

Chuck Reece: If that name is unfamiliar to you, let me help you out. At the Black Banjo Gathering, Flemons met several young African American folk musicians, including a woman named Rhiannon Giddens. When Flemons moved to North Carolina, he and Giddens, along with another musician from the gathering, Justin Robinson, formed a band called the Carolina Chocolate Drops. The following year, they released their first album, Dona Got a Ramblin’ Mind, and began touring.

MUSIC: The Carolina Chocolate Drops – “Starry Crown”

Chuck Reece: In 2010, they released their second album, the pointedly named Genuine Negro Jig, and suddenly the entire world seemed to know their name. The Carolina Chocolate Drops became the first African American band ever to play the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville. Their album hit the top of the Billboard Bluegrass chart, and they picked up the 2010 Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album.

Here’s Dom Flemons again.

Dom Flemons: The Carolina Chocolate drops — we always called ourselves the performing arm of the, of the Black Banjo Gathering, because we were always presenting the story that the gathering was presenting as well, which was that there was this very deep, long-seated history that is a part of this instrument, and that adding that piece to the tapestry of the banjo's history will change your whole outlook on everything. Not just the instrument or the or the, the music that it makes, but the whole spectrum of — of American culture after — after that. And that was something that we did in every show.

Chuck Reece: By the time that Grammy-winning album came out, the whole nation was looking more deeply at Black culture.

Dom Flemons: To kind of give it some context as well: These are the years leading up to President Obama becoming — becoming president as well. So this is sort of, in part of the upward movement of Black culture becoming mainstream. And so even the idea of Black string band music coming into play, this was also something that was part of a much bigger movement that was going on, especially in the United States, where there was a recognition and a reckoning on how Black culture was going to be viewed holistically on the ground level — outside of it just being only basketball and hip hop and things like that.

Chuck Reece: In the process, the Chocolate Drops forever changed the notion that the banjo was exclusively a white instrument, that it represented only bluegrass music.

Dom Flemons: One of the things that was so important about what we were able to do in the Chocolate Drops was to break the spell on people, when it came to feeling that the banjo could be limited in terms of who was playing the banjo. I think that one of the biggest things we were able to do as a group was to change people's perception about who could play the banjo.

ACT THREE

MUSIC: Hannah Mayree – “Home”

Chuck Reece: The first Black Banjo Gathering in North Carolina nearly 20 years ago started a cultural wave that is still swelling.

Hannah Mayree was 16 years old at the time of that Gathering. Although she grew up in California, her family’s roots are in the South. Her grandmother was born and raised in Central Florida but headed west to California during the Great Migration. Today Hannah and her family live in northern California, in Mendocino County.

When she was younger, many of her friends in California scoffed at the South. That made her curious about her grandmother’s Southern roots.

Hannah Mayree: And so I wanted — as a young person, I felt like it was really important for me to kind of dismantle that, through my own traveling and making personal connections with, like, my family, my bloodlines and with just the rest of the community so that … I was sort of stuck feeling like I was somehow like, separate or better because I was from this state.

Chuck Reece: So Hannah hit the road and lived the troubadour’s life: walking, hitchhiking, and hopping freight trains throughout the South. She stayed on the road for a long time.

Hannah Mayree: I spent a lot of time traveling, like, I spent years, like most of at least a decade. And so, yeah, when I spent time in the South and then I spent time in Georgia, it was definitely for like, weeks and months at a time.

Chuck Reece: Along the way, she played music in the streets. And her time in the South led her to pick up the banjo. Many of her peers did not react well.

Hannah Mayree: There was so many people that were having reactions to me playing the banjo that were basically telling me that I didn’t match a description of somebody that would play the banjo. And so that was something that I had to really dig into to try to be like, why am I keep on getting this reaction? Like they really just are not aware of where the banjo comes from.

Chuck Reece: Right.

Hannah Mayree: And they're bringing a lot of these ideas into their interactions with me that were signaling to me that the banjo belonged to white culture. And I, I was very much just like, "This is not accurate. This is not inclusive." And so that was what prompted me to, you know, find other voices who were part of the culture of the banjo.

There wasn't this narrative of Black people being included in what people's conception was of the banjo. And that it's just something that you have to dig up a lot deeper for.

Chuck Reece: Hannah did dig deep. And now she’s helping other Black people dig in, too. In late 2019, she founded a group called the Black Banjo Reclamation Project. The BBRP has taught the history of the banjo and held banjo-building workshops in California. Their work has spread to Chicago, where the group is teaching the story of the banjo to Black children, even teaching them how to build the instruments themselves. Dom Flemons has done some work with the BBRP in Chicago.

I find it spectacularly encouraging that this instrument has become a way for all Americans to learn their history and to see across cultural barriers. We have clearly come a long way from the "paddle-faster-I-hear-a-banjo days" of a half-century ago.

Rhiannon Giddens, who co-founded the Carolina Chocolate Drops with Dom, has gone on to win her own Grammys and multiple other music awards. In 2017, she was awarded the Macarthur Foundation’s so-called Genius Grant.

A year after that, in 2018, Giddens summed up the banjo’s importance in an unforgettable talk at the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Tenn.

Rhiannon Giddens: When you really dig deep into the music that lies at the heart of so much American history and gave birth to so many of those cherished record-bin genres that have captivated the world, you realize that the story hasn't even begun to be told: That world music has been around for hundreds and hundreds of years, that Africa met Europe far before the invention of the banjo, and that we are always an amalgam of the endless and numerous meetings, cultural exchanges, and influences of normal, ordinary people upon which civilization turns.

And when we pick out one narrative from the weave, and let it stand as the whole, it weakens us all. It's something we live with in this country: the little, tiny boxes, not made of ticky-tacky, but of ignorance, that we like to force our culture into.

There's no Black or white in this, ultimately. There's years of fusing, of melding, of becoming something that appeals to everyone. But when you neglect to tell part of the story, the whole thing can collapse. When you reinforce, through the segregation of music, the idea that we are so different — that some of us are the other, that we really can't just get along, that we belong in different bins, when the truth is so much bigger, better, and far more interesting, you threaten the very idea of who we are as people.

Chuck Reece: The banjo, if we will but listen to it — not to just one type of banjo tune, but to ALL of its music, played across centuries — it can teach us how we are all connected. And show us exactly why, long before we could write our stories down, we told them to each other through music.

CONCLUSION

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank Jeff Mosier, whose friends and fans call him Reverend Jeff, because he unceasingly evangelizes the story of the banjo.

We’d also like to thank Wayne Martin at the North Carolina Arts Foundation.

Hannah Mayree at the Black Banjo Reclamation Project. You can learn more about their work at BlackBanjoReclamationProject.org.

We must also thank the good folks at the Big Ears Festival.

We’d also like to thank an Atlanta musician named Grant Marshall, who provided us with some banjo music for this episode's score. You can find more information on Grant's bluegrass band Clawdad at c-l-a-w-d-a-d dot com.

And finally, we thank Dom Flemons, who graciously rushed to speak with us, even though he was still jet-lagged from a European concert tour. You can follow Dom’s work and his touring by going to TheAmericanSongster.com.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe episodes, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, an online magazine and a sort of haven for Southern storytelling which you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com

Our producer is the most excellent Jake Cook, who also composed our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell. Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief at GPB are stalwart supporters of Salvation South, and we are eternally grateful to them.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece goes deep into the complicated history of the banjo, from its origin on the shores of the Caribbean and West Africa to its rise as a ubiquitous icon of Southern "hillbilly" culture and beyond.