Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: Movement Music - Soul Music and Civil Rights

Primary Content

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece talks with Peter Guralnick, acclaimed biographer and author of Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom, and soul music legend William Bell, about the deep connection between soul music and the civil rights movement. Learn how this quintessential American artform was the catalyst and soundtrack for remarkable social change.

TRANSCRIPT:

Chuck Reece: When I was a teenager, a coworker of my father’s, a young man fresh out of college, turned me on to Otis Redding. Otis was the “gateway drug” to my lifelong addiction to Southern soul music. I fell in love with Otis.

MUSIC: Otis Redding - "Sittin' On The Dock of the Bay"

Chuck Reece: …and Aretha Franklin…

MUSIC: Aretha Franklin - "Think"

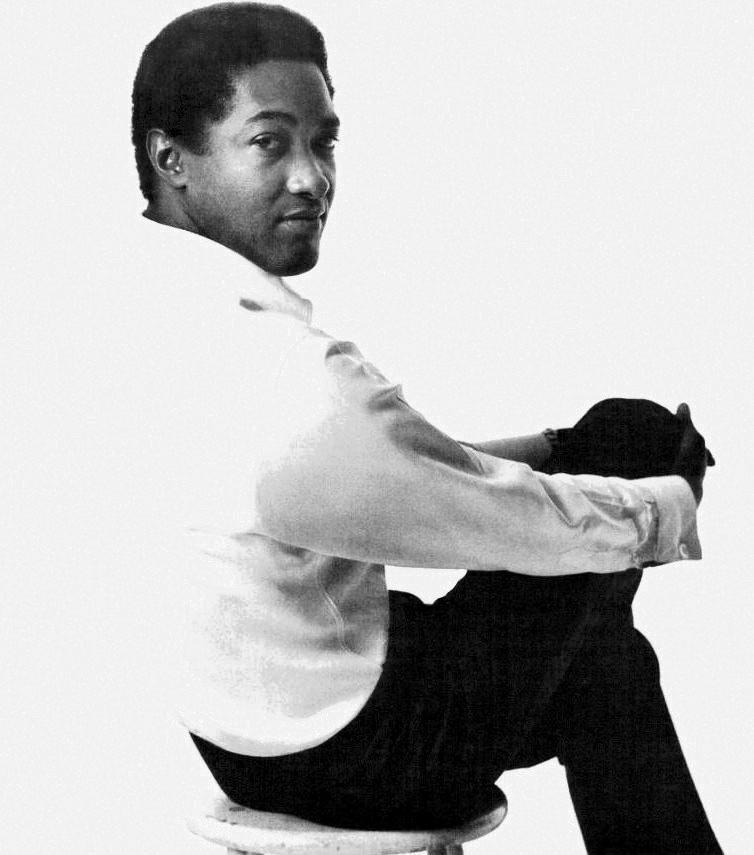

Chuck Reece: …and Sam Cooke…

MUSIC: Sam Cooke - "Shake"

Chuck Reece: Soul music made me want to dance. It just made me wanna shake and sway, wiggle and shimmy.

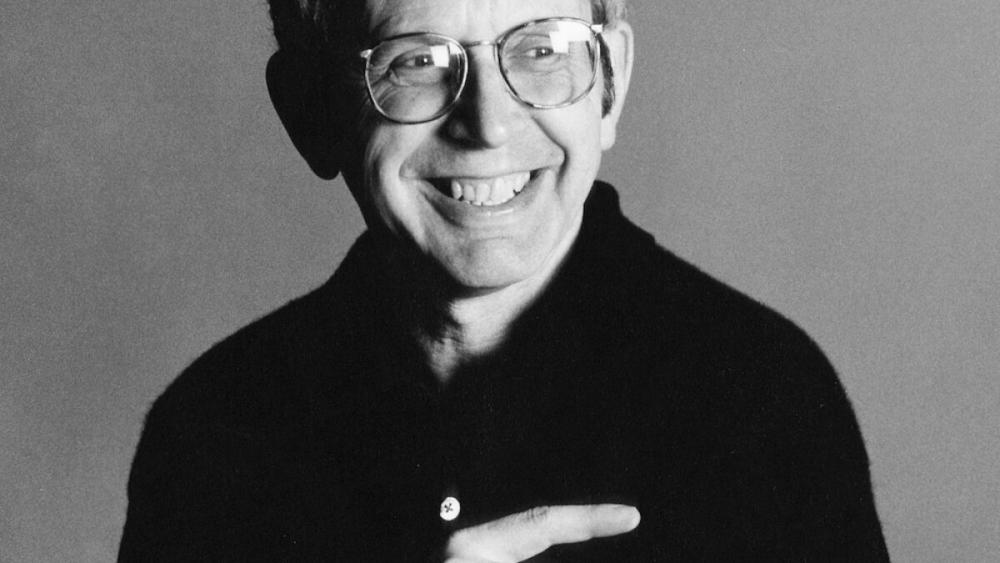

Now I knew, of course, that all this music was made by people whose skin, unlike mine, was Black. But I didn’t really figure out the deeper significance of their music until I was in my late 20s. I was living in New York City, and I saw a piece in the Village Voice about a book that was soon to come out. Sweet Soul Music, it was called. A music writer named Peter Guralnick wrote it. I went to see him talk about the book in Manhattan, and I came home with a copy. And that book taught me about soul music’s bone-deep connection to the civil rights movement.

Peter Guralnick first taught me that soul music was intended to bulldoze the Jim Crow barriers between Black kids and white kids in the South. It was indeed music to move your body to, but it was also music that fueled a movement. It was “movement music,” from every possible perspective. Earlier this year, I had the great good fortune to chat with Peter, who, at age 81, is still writing, as always, about music. On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe, I’ll let you in on that chat — and another I had with one of the few surviving hit makers from the glory days of Southern soul, William Bell.

Together, we will learn how what sounded like teenage party tunes became the soundtrack of Black Southerners’ dreams of freedom from Jim Crow.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to this episode of Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed. Here on Deluxe, we shine some light on untold stories of the Southern experience and let you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

THEME MUSIC OUT

ACT ONE:

Chuck Reece: When I told you about my first exposure to Guralnick’s book, Sweet Soul Music, I did not tell you the book’s subtitle: Rhythm & Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom. This is Peter Guralnick.

Peter Guralnick: What led me to write the book was the music. But what led me to explore the connection was that it was so evident and so present. It was present in absolutely everything that you looked at. In terms of connecting it to the civil rights movement, the music in so many ways was helping to bring barriers down, both metaphorical and physical.

Chuck Reece: We all know about the metaphorical barriers, so let’s pay a bit more attention to the physical ones. In the Jim Crow days of the early 1960s, Southern kids who had different skin colors could not hang out at the local diner and have a burger together. Every public establishment had separate bathrooms and water fountains for each of the races. The lives of Southerners were segregated by law. But the concerns of Southern teenagers were not segregated. All of them wanted to dance. They heard Sam Cooke do “Having a Party,” and they wanted to be at that party.

MUSIC: Sam Cooke - "Having A Party"

Chuck Reece: Another thing that wasn’t segregated? The Billboard “Hot 100” chart, which ranks the nation’s most popular songs. Billboard Magazine launched that chart in 1958, and it was integrated from the beginning. With Black soul artists topping the chart, their concert tours made big money. But when they played in the South, there were not always segregated venues. So Black and white ticket holders sat in different sections, often divided by nothing more than a rope line.

Peter Guralnick: Everybody will tell you about the rope that stood up between the Black and white side of the audience or the Black audience or the white audience be confined to the balcony. The point is, at some point during the show, the rope came down — in a sense, the opening up to different cultures, different ways of looking at things, to different ways of hearing. The music so much brought people together who otherwise were very unlikely to come together.

Chuck Reece (from interview): Was there a certain point in your research when you began to realize that the book would need a subtitle like "Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom"? Did you find yourself having to take your research in different directions when you began to explore that connection between the music and the civil rights movement?

Peter Guralnick: I see myself as a writer, later as a biographer, as just setting out on unknown territory and I don't really know where I'm going to end up. It's an exploration ... without a particular or explicit goal. So it takes you wherever it goes. One thing about the subtitle of the book, "The Southern Dream of Freedom", was implicitly to express the fact that it wasn't strictly racial. It wasn't all Black, it certainly wasn't all white. It included a great many people who made an enormous contribution and were all imbued with the same belief and feeling.

Chuck Reece: Peter long ago dedicated his life to writing about music, and he's responsible for books that are widely acknowledged the definitive biographies of:

- Sam Cooke — a 2006 book called Dream Boogie;

- Sam Phillips, the founder of Sun Studio in Memphis, where Elvis Presley made his first records — a 2015 book called The Man Who Invented Rock ’n’ Roll;

- And his two-volume biography of Elvis himself — 1994’s Last Train to Memphis and 1999’s Careless Love.

A common thread through all his interviews with musicians, he says, is that the greatest ones tend to disregard the racial barriers that so many people in our broader society cling to.

Peter Guralnick: One of the things that has struck me in all the people that I've written about over the years, whether it's Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash or Howlin’ Wolf or Muddy Waters, one of the things that struck me is that they have the most democratic views when it comes to music, when it comes to art. ... I'm not going to say what their views were politically. That isn't my area. I mean, it's not for me to say. But the point is, as artists, as musicians, they were open to absolutely everything. They incorporated everything they heard.

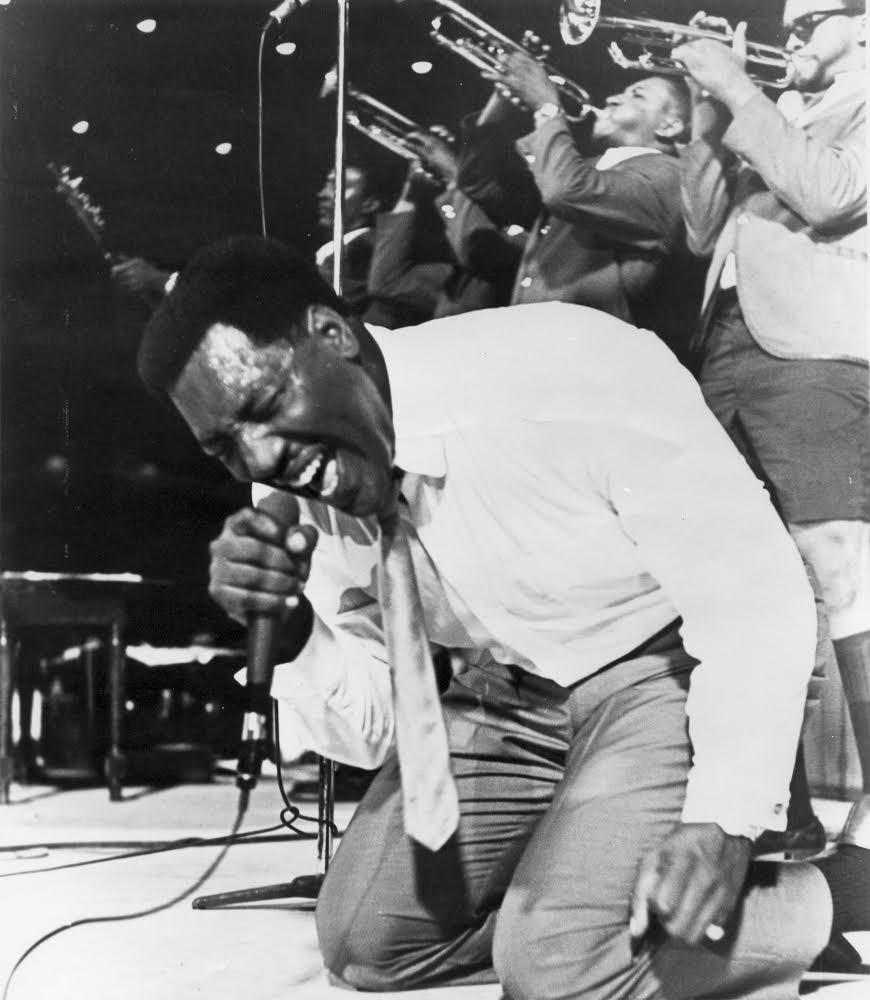

MUSIC: Solomon Burke - "Everybody Needs Somebody to Love"

Chuck Reece: That’s the voice of the great Philadelphia soul singer Solomon Burke. Peter remembers being shocked to learn, over his repeated interviews with Burke, that his musical idol was the Texas cowboy singer Gene Autry.

MUSIC: Gene Autry - "Back in The Saddle Again"

Peter Guralnick: Solomon Burke would talk about Gene Autry and how Gene Autry was his idol as a child. He learned diction, articulation from Gene Autry. You know, he would make a point, he says, when Gene Autry sings he doesn't say "bahh in the sahh 'gain" He says, "back in the saddle again.” So he would do it very with great clarity. But he admired him. So, I mean, the music was just something. There were no barriers among the people. All the many people that I've talked to, I can't think of a single one who saw the barriers as far as walls, as far as music went. What categories? They just embraced what they heard.

Chuck Reece: At Stax Records in Memphis, Tennessee — arguably the birthplace of soul music — Black and white artists were recording the hits together. They couldn’t take a dinner break together at the same restaurant, but they were building grooves together for the likes of Otis Redding and Sam & Dave. The house band at Stax — Booker T. & the MG’s —was integrated. Two Black musicians — keyboardist Booker T. Jones and drummer Al Jackson — and two white: bass player Donald “Duck” Dunn and guitarist Steve Cropper.

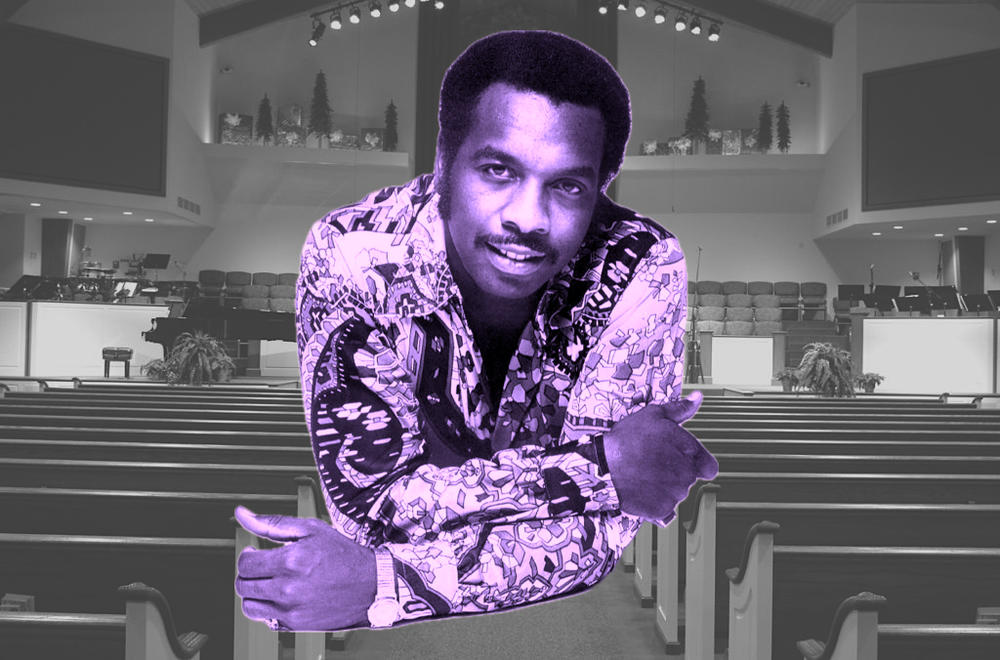

The very first singer and songwriter Peter Guralnick interviewed for his Sweet Soul Music book was the first solo artist to be signed by Stax in 1960. His name is William Bell. William wrote hits for Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, and himself — including my favorite Christmas tune of all time.

MUSIC: William Bell - "Every Day Will Be Like A Holiday"

Chuck Reece: We talked to William, who has lived in Atlanta for many decades and is still, at age 85, writing, producing and recording music.

William Bell: People are people, and that's the world over. Uh, the human nature of people. The times change, the living conditions might change, but the human factor or how you deal with living remains the same. And so people can relate to something if there's real — if it's real about it, and you're telling the truth about how it feels to be left alone by your loved one or how it feels to be discriminated against or whatever the situation is. If you feel that you do an honest job of that, no matter what generation you are, and when you start communicating with other individuals, that same feeling is going to creep in. And that's in every country — and I've traveled extensively, and sometimes in countries that people don't even understand the English language. They feel what you're portraying and what you're trying to project, in the way you sing a lyric — just the same as we do when we listen to opera.

Sometimes I listen to Madame Butterfly — some things I don't understand. I understand what I call survival Italian, but I don't understand, uh, fluent Italian. But I can listen to an opera, and I understand it because of the emotional value of it. It's the same thing that people do in every generation and every race, creed, or color. I mean, because we all have the same wishes, frustrations, desires or whatever.

MUSIC: "Un bel dí vedremo", performed by Ermonela Jaho, fom Madama Butterfly

Chuck Reece: Salvation South Deluxe will be right back after this short break.

MID ROLL BREAK

ACT TWO

Chuck Reece: Welcome back to Salvation South Deluxe. When Black singers like William Bell went on tour through the South in the early '60s, at the height of Jim Crow, they had to be careful. Motels that would let Black people check in, restaurants where they could eat, were few and far between.

But when they packed up and drove through the night to the next gig, they had help from deejays at clear-channel AM radio stations whose signals reached far and wide. All of those deejays were white, but all of them in love with soul music. And those deejays would pass along critical information. Let me read you a short passage from Sweet Soul Music. Peter’s writing about John R., a legendary deejay at WLAC-AM in Nashville.

As they heard their records being played and kept track of chart positions, the performers themselves would call in to John R., who would relay their location to a waiting world of teenagers, rural Blacks, and fellow musicians. 'Just heard from Otis Redding in Midland, Texas, he’s going to be doing two shows tomorrow night in Little Rock for all you folks out there in the Little Rock area.'

Chuck Reece: And the people in Little Rock would be waiting to help them when they arrived. This network — called the “hip-ocracy” — kept the touring musicians safe, and eventually they realized their combined power could aid the fight for civil rights. White racists in the South had their Ku Klux Klan. But these singers wanted their own clan — and they called it the Soul Clan. One of the key instigators in the Soul Clan was the aforementioned Solomon Burke.

Here’s Peter again.

Peter Guralnick: I mean, someone like Solomon, he was a star and he was larger than life. I'd say along with Sam Phillips, he was the most charismatic person I've ever met and one of the most brilliant. And he recognized — he really did recognize the broader framework and the broader context in which he had achieved what he did, what he did achieve and contributed what he did contribute.

When Solomon came up with the idea of a Soul Clan, they put the idea of all of these great artists getting together was to form a wedge. I mean, to put their strength, their power together. Solomon's sort of flighty inspiration was to buy a whole territory, to buy hotels, motels, you know, to move to a particular place, take over the building. I don't think that was ever a realistic part of the plan, but it was certainly part of the metaphor.

Chuck Reece: But Solomon Burke’s expansive vision did encompass Black stars outside the world of music.

Peter Guralnick: The Soul Clan spoke of acquiring power of somehow or other spreading the power that they had. Sam Cooke, Jim Brown the football player, and Muhammad Ali met at the hotel in Miami after Ali took the fight — he was then Cassius Clay — from Sonny Liston. Those people, Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali and Sam Cooke occupied a similar place and a similar ambition to what the Soul Clan, at its most ambitious, aspired to be.

Chuck Reece: The amalgamated power of such Black stars was potent, yes, but not potent enough to keep white Southern racists from harassing them. William Bell remembers a particular night in Memphis.

William Bell: I remember one night Steve Cropper and I were working mixing in there late, and we walked out about 2 in the morning and turned around to lock the doors of Stax Records, and the police were sitting across the street. They had a grocery store over there, across the street from Stax, called the Big D, and they were sitting in the parking lot. So they screeched over, jumped out, guns drawn and everything, and put us up against the wall and everything. And they were talking about breaking in. We've got keys, locking the door. I mean, how can we be breaking in, you know? But they knew that it was just to harass us. They would let us go and we'd hop in the car. They always wanted him to get in the back seat; he would get in the front seat beside me. We would drive home in one car, and they would tailgate us like maybe two feet from our bumpers, just hoping we would swerve or something so they could pull us over. Then after I would drop Steve off at his house, they would follow me home until I got home and, uh, and sat there out in front of my house until I pulled up in the driveway and walked in the house. It was just — just harassment.

Chuck Reece: But the joy and fulfillment of making such amazing music kept artists like William coming back to that studio, every day.

William Bell: All we cared about was what you brought into that studio in terms of creativity. If you could write, you could sing or you could play, whatever the situation was, we wanted you to do the best that you could. And we just got together inside those confines of the studio, whether it was Sun or Stax, and had a great time.

Peter Guralnick: All of them saw themselves as being part of the movement, whether they liked it or not, to the extent to which they were victimized, the extent to which they had the experiences on the broadest scales, you know, that William Bell had described to you as having in Memphis. The way in which they were out there in many ways without protection. And in areas that were the hotbeds, the seedbeds of the civil rights movement. They couldn't escape it. They were soldiers, whether or not they chose to be.

Chuck Reece: Some took on the soldier roles because they felt they had no choice. And others, like the North Carolina-born Clyde McPhatter and South Carolina’s Brook Benton, embraced it. McPhatter had been lead singer of the Drifters through the 1950s, and had gone on to a solo career during soul’s boom in the early ’60s, with hits like this one…

MUSIC: Clyde McPhatter - "A Lover's Question"

Chuck Reece: Later that decade, Benton would hit the top of the charts with a ballad that’s familiar to pretty much everyone here in Salvation South’s home state…

MUSIC: Brook Benton - "Rainy Night in Georgia"

Chuck Reece: This is Peter again, reading from Sweet Soul Music.

Peter Guralnick: Clyde McPhatter and Brook Benton, for example, were two people who articulated very strongly. You knew what their feelings were, being out there on the front lines and though not necessarily by choice, just out of necessity, as I say.

Clyde McPhatter said, 'We travel all over. There's hardly one entertainer who hasn't felt the strain of prejudice or the crack of Jim Crow. And there was no one,' he said, 'who wouldn't give his all of his all to erase these things from the face of the globe.' Brook Benton said, 'A Negro performer doesn't really know where he stands. We're waking up. We're tired of being pushed around. What are we, dogs? These Negroes in Alabama have right on their side. They're not citizens. No matter what it says in the books, they're not free. They're slaves.' But Brook Benton was concerned. He doubted that he could maintain a nonviolent stance. 'I'm probably going to have to get me a gun or a knife or a few bombs.'

Chuck Reece: And maybe the greatest singer of them all, Sam Cooke, of Clarksdale, Mississippi, never shied away from speaking out.

Peter Guralnick: Sam Cooke, for example, certainly saw the role he was cast in. And when he refused to play a show in Memphis in 1961 — neither he nor Clyde McPhatter would play the show — because of the segregated seating, he was aware of the consequences of his action. He wanted to erase, you know, the racial distinctions.

Chuck Reece: Peter Guralnick says the great Black writer James Baldwin probably captured the spirit of that era better than anyone.

Peter Guralnick: James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time, which was an inspiring book, James Baldwin is writing about a community in which imagination and self-invention trumped pedigree in which, as he wrote,

'There existed, quote, a zest and a joy and a capacity for facing and surviving disaster. Very moving and very rare. Perhaps we were, all of us pimps, whores, racketeers, church members and children bound together by the nature of our repression, the specific and peculiar complex of risks we have to run.' If so, he said it was that inescapably shared heritage that helped create the dynamic that allowed one to, quote, 'respect and rejoice in life itself and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.'

It was that freedom, that presence, that vitality which Sam Cooke sought to celebrate. It was that experience which he supposed to embody and transcend. And that, to me, was the heart of the biography of Sam Cooke. And much more important than any individual. Much more important than looking upon Sam Cooke, as great as he was as a superstar, But much more to do with the community from which he came and to which he contributed so much.

Chuck Reece: Sam Cooke died far too young, when he was only 33, when he was shot and killed in Los Angeles in December of 1964.

But earlier that year, he had written and recorded a song that would become the anthem of the civil rights movement as it proceeded throughout the '60s. Cooke wrote the song only four months after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. told a quarter million people in Washington about a dream he’d been having. Sam Cooke’s song was a hymn to his faith in that dream. Today, 60 years later, that song — “A Change Is Gonna Come” — still resounds as the anthem of people who share Dr. King’s dream.

MUSIC: Sam Cooke - “A Change Is Gonna Come”

CONCLUSION

Chuck Reece: You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe — a very special episode that could never have happened without the grace extended to us by two wonderful people. First, we have to thank Mr. William Bell. I am so very glad that he is still with us and still making music that speaks to the same hope that lived inside Sam Cooke. William’s latest single, in fact, which came out only a couple months ago, is called “Strange Fruit Is Still Hanging.” Amen to that. I must also thank Peter Guralnick — first for opening the eyes of a Southern white boy like me to the underlying significant power of the Black music I’d fallen in love with, and second for being one of my all-time writing heroes.

We are deeply grateful to both men for sharing their knowledge and memories with us. If you would like to listen to the music we’ve been talking about, we’ve got a playlist of every song mentioned in this episode — plus a few bonus tracks — on the Salvation YouTube channel and in Spotify and Apple Music. And you can find links in the show notes of this episode.

Salvation South Deluxe is proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of 20 stations around our state. I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, an online magazine about our region which you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com.

Our producer is the extremely funky Jake Cook, who also composed our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell, and the Salvation South podcast could not exist with the help and support of wonderful people at Georgia Public Broadcasting like Sandy Malcolm and Adam Woodlief.

Every week, we add a short commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and we’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of Salvation South Deluxe.

✦✧✦✧✦✧✦✧✦✧

Listen to Chuck's Southern Soul Playlist:

Spotify

Apple Music

YouTube

✦✧✦✧✦✧✦✧✦✧

If you liked this episode, you'll also enjoy this one, featuring more of Chuck's talk with soul music legend William Bell.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South.

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece talks with Peter Guralnick, acclaimed biographer and author of Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom, and soul music legend William Bell, about the deep connection between soul music and the civil rights movement. Learn how this quintessential American artform was the catalyst and soundtrack for remarkable social change.