Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: Me and The Devil

Primary Content

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe, we're debunking the Robert Johnson myth. We'll explain how the "deal with the devil" story overshadowed a blues genius and led to exploitation of his legacy.

TRANSCRIPT:

Chuck Reece: A long time ago, I sat on a porch in the mountains with a fantastic storyteller. Listened to him spin a tall tale that wound back and forth like the switchbacks on the road I took to get up there. When he finished his unbelievable story, I looked him straight in the eye and said, “That’s crazy. That can’t be true.”

He looked me right back and said, “Son, NEVER let the truth get in the way of a good story.”

Ever since, I’ve wondered, what is the tallest of all Southern tall tales? And I believe I have the answer. It’s a story you probably know, one that has spread all over the world and been repeated consistently for nearly a whole century ever since it happened. Or didn’t happen.

The story is about a poor man in the Mississippi Delta, born into a family of sharecroppers, who desperately wanted not to work the fields, but instead, to play music. His name was Robert Johnson. One dark midnight in the 1930s, he sold his soul to the devil, and in return got the ability to do this…

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "Hell Hound On My Trail"

“I got to keep movin’ / I got to keep movin’ / Blues fallin’ down like hail / Blues fallin’ down like hail / I got to keep movin’ / Hellhound’s on my trail.”

Chuck Reece: But I did not come here today to tell you the story of Robert Johnson selling his soul, because you already know that story.

Instead, I will tell you how people around the world contributed to the mythology around the life of Robert Johnson. And how the myths became essential to Southern folklore, and then American folklore, and eventually spread around the entire world. I will also tell you the story of how one of the people who built that mythology — a troubled Texan named Robert “Mack” McCormick — became so obsessed with Robert Johnson that he tried to steal the rights to tell Johnson’s story from the musician’s own family. Finally, I will tell you how the myth that Robert Johnson was a hapless Black character in a crazy story … made it easier for white Southerners of the 20th century to dismiss two truths that made them uncomfortable: One, that Robert Johnson didn’t need the help of the devil to make music so inventive that no one in the 1930s had ever heard anything like it. And two, that Johnson had turned himself, through his own hard work, into one of the most innovative musicians in the history of our nation.

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "Me And The Devil"

“Me and the devil’, walkin’ side by side…”

Chuck Reece: Today, on Salvation South Deluxe, we’ll try to do musical justice to a Southern musical genius, whose influence over musicians around the world is monumental and absolutely without parallel.

I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed. On Salvation South Deluxe, we shed some light on parts of the Southern experience that have been kept in the shadows and let you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

ACT ONE

Chuck Reece: Whether the story of Robert Johnson meeting the devil himself at crossroads U.S. Highways 61 and 49 in Clarksdale, Miss., is true or not, we must admit that it is a wonderful story. I think it’s absolutely fair to say the story is THE quintessential Southern tall tale. Not because it happened at a literal crossroads, but because it sits at another crossroads — the one between sin and redemption, which has haunted our region for centuries.

This is John Troutman, a man originally from Dothan, Ala., who is now the curator of music and musical instruments at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington.

John Troutman: In terms of the crossroads story, you know, in the South, it's like that dialectic, that dualism. The “Saturday Satan, Sunday saint” kind of life of intersections and crossroads is so prevalent and so powerful. And especially in more kind of Protestant, evangelical pockets of the deep South, as you know, it’s — the devil is everywhere.

The devil is an active character in the lives of many people in the South.

Chuck Reece: Old Scratch, Satan, Beelzebub — whatever you choose to call him — was an active character in Robert Johnson’s life, too. Just like it was in nearly every other Southerner’s life in the 1930s.

Kimberly Mack is a music writer and scholar. She is an associate professor at the University of Illinois who studies and teaches African American literature, culture, and music.

She is also the author of a fascinating book called Fictional Blues: Narrative Self-Invention From Bessie Smith to Jack White. It’s a brilliant, eye-opening book about why the blues are such fertile ground for the creation of mythologies.

Kimberly Mack: Particularly with Robert Johnson, the fact that there are very few details. And we you know, we're getting more and more details, which is great as time goes on. But certainly at this time period, you know, in the middle of the century, 50s, 60s, there was not much of anything about his life and the things that we did know or we thought we knew were so fantastical.

Chuck Reece: There is no indication in the historical record that Robert Johnson ever told anybody about any deal with the devil. But we do know that his ideas about the devil were part of what made his music so different.

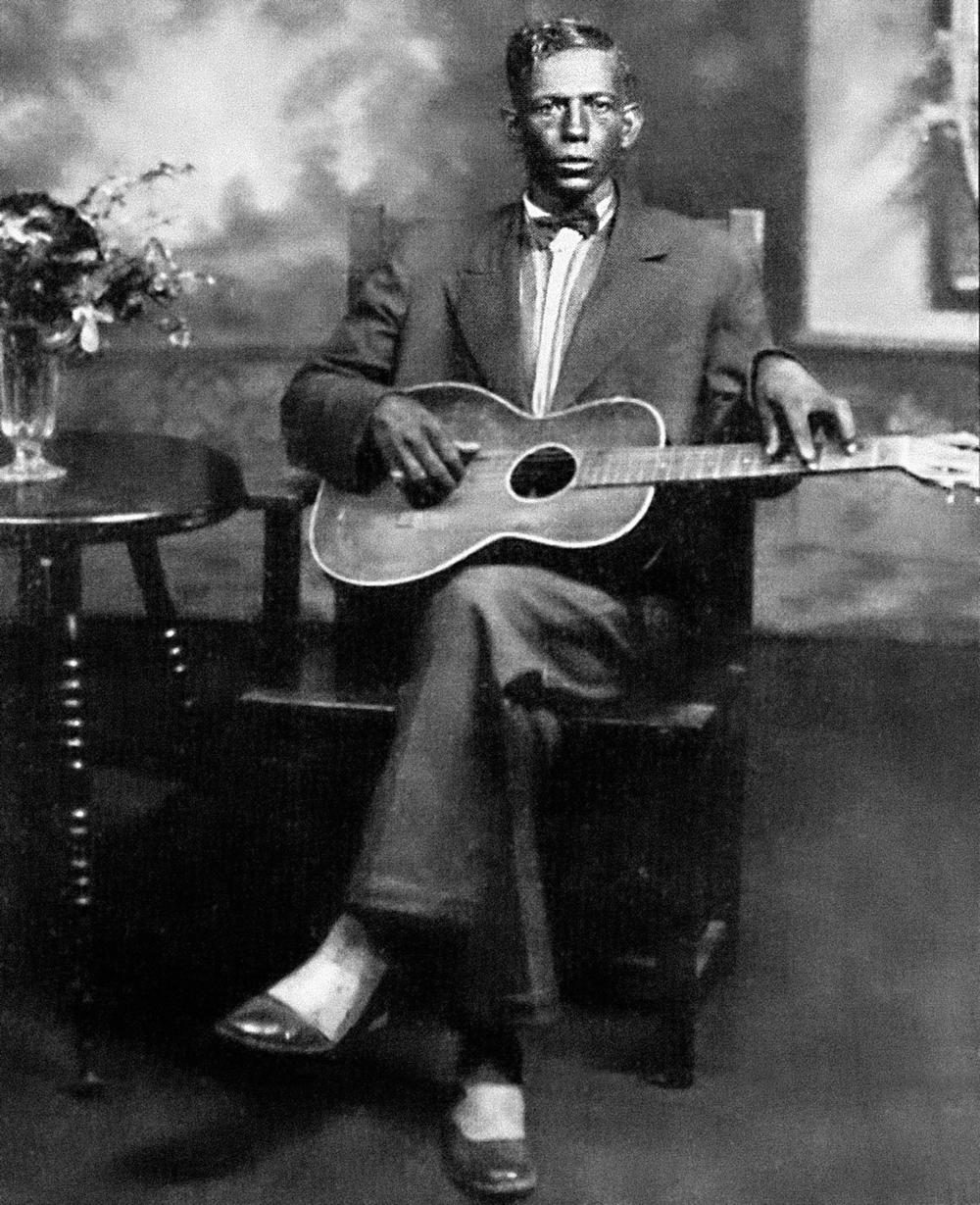

People who study the beginnings of the blues in the Mississippi Delta usually point to three originators. The oldest, Charley Patton, was born in 1891 in Hinds County, Miss. He is usually called “the father” of Delta Blues.

MUSIC: Charley Patton - "Moon Going Down"

Chuck Reece: Then there was Son House — properly, Edward James House Jr. — born in 1902 in Riverdale, Miss.

MUSIC: Son House - "Death Letter Blues"

Chuck Reece: Robert Johnson, born in 1911, was the youngest of the three. And he had attributes neither Patton nor House possessed.

Patton’s voice was deep and gruff, House’s was in the middle register, but Johnson’s keened and wailed like the cries of a desperate man. And his skills on the slide guitar could echo those cries.

But it was more than the sounds he could produce that made Johnson’s music different. It was his subject matter. Johnson’s songs were erotic. Sometimes downright salacious.

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "Traveling Riverside Blues"

“Now you can squeeze my lemon till the juice run down my leg (till the juice run down my leg, baby).”

Chuck Reece: His lyrics played around with religious imagery.

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day"

Chuck Reece: And with dark, supernatural forces.

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "Me And The Devil Blues"

“Early this morning, when you knocked upon my door / And I said, ‘Hello, Satan. I believe it’s time to go.”

Chuck Reece: Johnson differed from Patton and House in another way that only added to his mystery: He died young.

Son House lived to the ripe old age of 86, and Patton to 43. But Robert Johnson died at age 27, from drinking poisoned whiskey. To this day, no one knows who poisoned the whiskey or why. So we're lucky to have his music at all. He played only two recording sessions in his life. They happened a year apart. The first, in San Antonio, Texas, in 1936, produced 16 different songs. At the second, in Dallas a year later, Johnson recorded 13 more.

Only 12 of those songs were released before Johnson’s death in 1938 — six 78-rpm records with one song on each side. But those recordings were so striking, so unlike anything anyone had ever heard, they caught the attention of the most influential record producer in America, John Hammond. Hammond, who had discovered Billie Holiday in 1933, was a crusader for bringing down the color barrier in the music business. In those days, records recorded by Black performers were referred to as “race music,” and they were rarely heard or purchased by white audiences.

So toward his goal of breaking down that barrier, Hammond, in December of 1938, Hammond staged a two-night series of concerts at New York’s Carnegie Hall called “From Spirituals to Swing.” It was a radical move: His aim was to showcase the mastery of African American musicians — gospel, jazz, blues, and swing — to an integrated audience. Hammond’s lineup included Count Basie, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and many others. And he wanted it to include Robert Johnson. Hammond asked Don Law, who had recorded Johnson in '36 and '37, to find him in Mississippi and ask him to come to New York for the concerts. But Law brought back to New York the news that Johnson had died.

Hammond, however, was so determined to introduce the Carnegie Hall audiences to Johnson’s music that he set up a record player on stage, pointed two microphones at it, and played “Walkin’ Blues.” Then he turned the record over and played “Preachin’ Blues.”

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "Preachin' Blues"

Chuck Reece: Hammond’s “From Spirituals to Swing” concerts became legend, and two important happenings followed. First, over the next 20 years, Hammond slowly acquired the license to 16 of Johnson’s recordings and released in 1961 under the name King of the Delta Singers. That’s when a British teenager named Eric Clapton first discovered Johnson’s music. And seven years later, in 1968, he would, with his band Cream, transform Johnson’s “Cross Roads Blues” —

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "Cross Roads Blues"

Chuck Reece: — into this:

MUSIC: Cream - "Cross Roads (Live)"

Chuck Reece: Secondly, “From Spirituals to Swing” inspired a loose-knit group of obsessive fans who became known as the Blues Mafia. Let me read for you John Troutman’s description of the Blues Mafia.

The phrase neatly characterizes a small but culturally impactful, global community of white, male fanatics of southern Black vernacular music who first began to find one another in the 1940s.

They traveled the South, looking for clues about the lives of Johnson and other obscure blues players and scooping up those 78-rpm records wherever they could. And with their efforts, the mythology around Robert Johnson’s life began to build.

Kimberly Mack: A lot of those folks, they were not Southerners. I mean, you know, a lot of them were coming from other places — white, predominantly middle class, young, coming from other places and wanting to tap into something that they felt was going to be real and pure and authentic. And that purity was rooted in a kind of, you know, racially essentialist thinking. So it was kind of like, "well, the real deal are Black men from the South." Specifically, a lot of them rooted in the Delta area. And those are the folks who are not plugged in, not electric, you know, that kind of lone man with a guitar romantic figure. Let's tap into that, because that's the real deal. That's the real stuff.

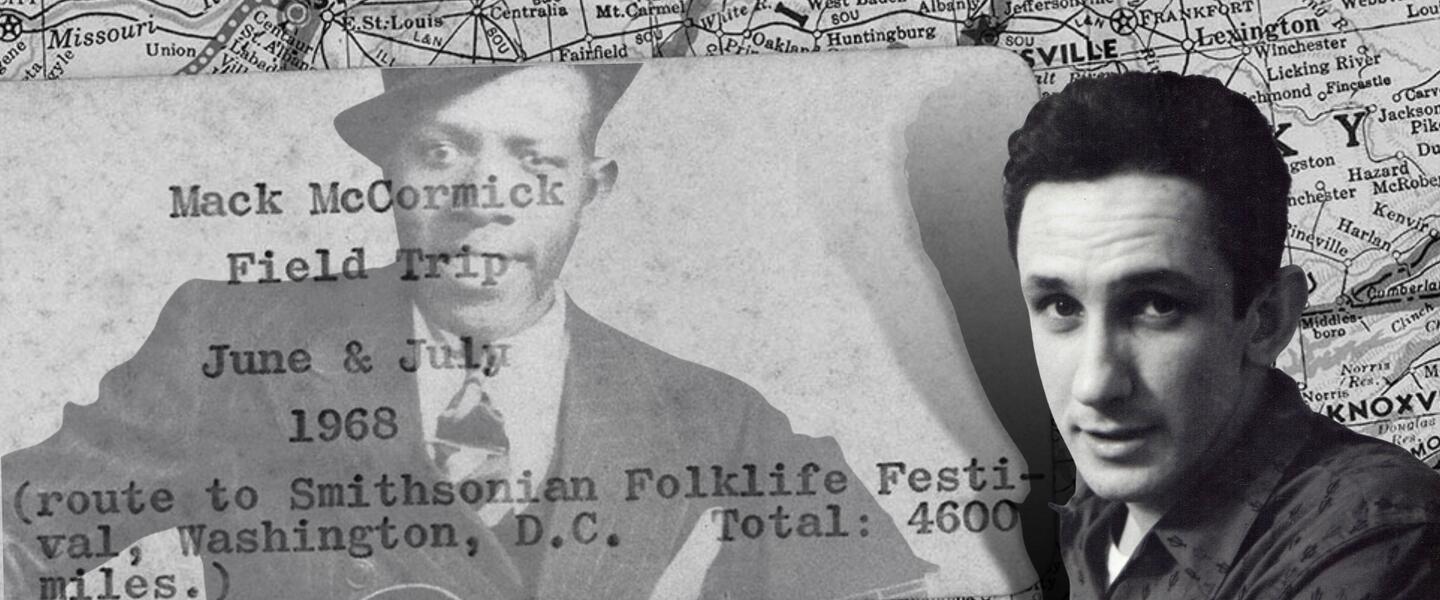

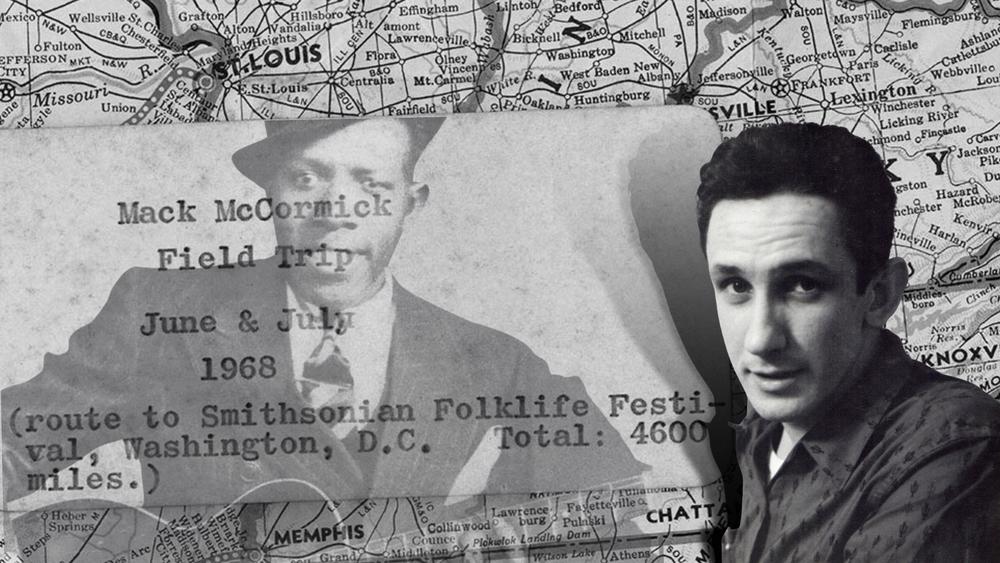

Chuck Reece: I mentioned one of the “made men” of that “Blues Mafia” at the beginning of this episode: Robert “Mack” McCormick. McCormick earned his stripes in the Blues Mafia when, in 1949, he became the Texas correspondent for Down Beat, a magazine founded in Chicago in 1934. Down Beat is still, 90 years later, a leading jazz publication.

About the Blues Mafia, McCormick himself wrote this:

They search, perhaps, because secretly they believe our roots may hold more beauty than our future. Their work can become an odyssey: a long, lingering hunt over a haphazard trail. The hunters are known by many labels: social documentarian, oral historian, folklorist, anthropologist. For some, such as myself, the obsession is to hunt the blues. Our search is not simply for the materials — the songs and music that make up the tradition — but more for the most authentic performers, that select group of short-lived creatures, fully as mad as symbolist poets, who roamed through the world, leaving only cryptic clues about their existence.

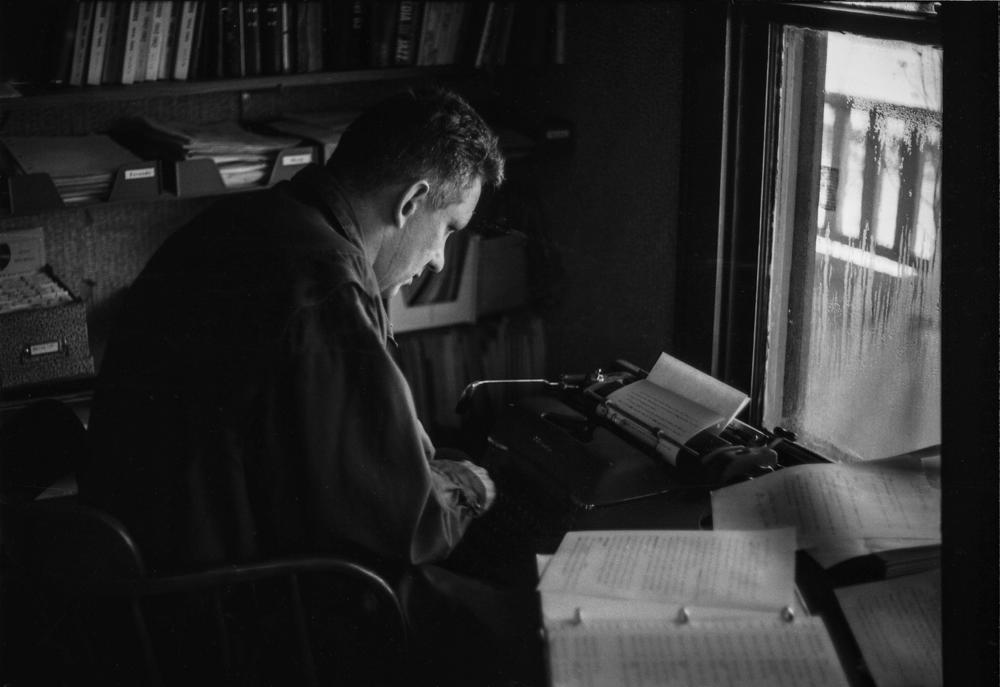

Chuck Reece: McCormick wrote about jazz and blues for Down Beat, but his greatest obsession was the late Robert Johnson. For almost fifty years, McCormick chased Johnson’s ghost obsessively and compulsively. Sadly, McCormick was wired to be obsessive. He suffered from long bouts of depression and other mental disorders until his death.

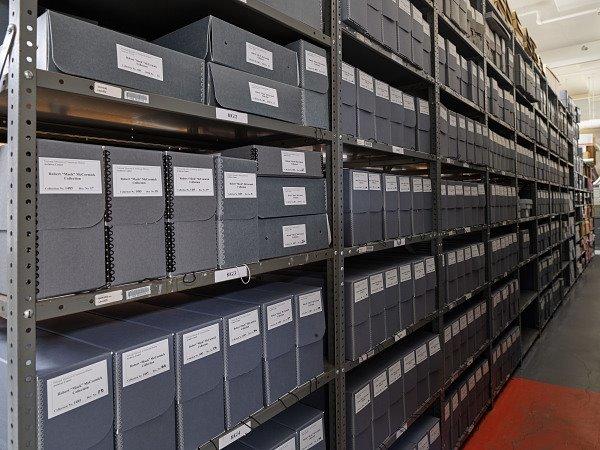

From the early 1970s to his death in 2015, McCormick wrote so many pages and collected so many documents about Johnson that, if you shelved them all on a football field, it would run from the goal line to the 30 — literally 90 linear feet. McCormick himself referred to it as “the Monster,” and only occasionally would he show anything from the Monster to anyone else. He guarded it jealously.

But when McCormick died, he still had not finished his book about Johnson, which he intended to call Biography of a Phantom. After his death, thanks to the careful actions of McCormick’s daughter, the Monster made its way to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. In it, we can now learn much more about Robert Johnson’s life.

We can also learn that one of Mack McCormick’s obsessions was a dark one — the idea that only he had the right to tell Robert Johnson’s story. That idea gnawed at McCormick so fiercely he would go to any means to tell the story the way he wanted it told — even to the point of forging documents that would have prevented Johnson’s surviving family members from benefiting from their famous forebear’s music and story.

After this short break, we’ll be back with John Troutman of the Smithsonian — and others. And this time, we’ll focus not on the mythology, but on the truth.

The truth about Robert Johnson. And the truth about Mack McCormick.

You’re listening to Salvation South Deluxe.

ACT TWO

Chuck Reece: The mythology about Robert Johnson and the devil had value in the 20th century, if only because it attracted young musicians to study his music.

A case in point is an Atlanta blues musician named Tinsley Ellis. For 45 years, Ellis has played the blues in Atlanta and all over the world. Over that career, he has released 23 albums. Ellis was one of those young white American men drawn to the blues — and to the mythology of Robert Johnson. He says he first heard the King of the Delta Blues Singers album when he was a teenager, in 1971.

Tinsley Ellis: That was the selling point initially, really, was the story about him going to the crossroads and falling down on his knees. And that was the explanation for his musical greatness.

Chuck Reece: But the blues from the beginning felt spiritual for Ellis. Important. Something to guard and take care of and nurture. So he was determined to go beyond the mythology. He wasn’t going to accept the devil story and not look deeper at the sources of Robert Johnson’s talent. Which is how Ellis learned the story of Ike Zimmerman. Zimmerman, in the late '20s and early '30s, gained fame on the Mississippi juke joint circuit — although his music was never recorded. We’ll let Tinsley Ellis tell the story of how Johnson met up with Zimmerman on his travels through the Delta.

Tinsley Ellis: He had been hanging around up in the Delta and some of the places that we're really known for, for blues, maybe Clarksdale and places like that, and hanging out with Sun House and Willie Brown and Charlie Patton and others. He went and traveled and went down and met up with this guy, Ike Zimmerman. And Ike Zimmerman was a guy who never recorded or anything, but he, Robert Johnson, lived with him. … Although Zimmerman was initially from Alabama. That was who became his his tutor, his teacher. So after — I don't know whether it was months or years, maybe a year — he came back to Clarksdale with all these chops. People don't really understand, you know, how that happened. So they've got to blow it up and make a tale out of it about how he sold his soul to the devil or something like that. But he came back and was playing on a whole different level. Consequently, he must have had some kind of a divine intervention or something like that.

Chuck Reece: Long story short: White people in the 20th century were more likely to believe that satanic intervention explained Johnson’s skills and artistry — and less likely to believe that he actually traveled and found mentors and teachers and worked hard to hone his skills. It was easier to believe that Robert Johnson could have made it to Carnegie Hall by dealing with the devil than to believe he got there the way everyone else did: practice, practice, practice.

Let’s listen to the music scholar Kimberly Mack again.

Kimberly Mack: One of the things that is a bit dangerous about those romantic ideas — and they are very romantic, you know, this lone blues figure trope — is that it does erase the very hard work and professionalism of these players. You know, these are folks who could play anything. These are folks who were recording. These are folks who were professional musicians who were working at their craft. And it does, you know — inadvertently, even if that's not the purpose — it does it does erase those efforts. And that is a problem.

Chuck Reece: But Kimberly acknowledges that with so few details available in the early 1960s about Johnson’s life, a dramatic story about a deal with the devil might have proven irresistible.

Kimberly Mack: I think when you have very few real, hard, concrete facts about something, it is like catnip for folks in terms of storytelling. I'll just say the top reason why Robert Johnson's myth, I think, lives on is that people just love stories, love storytelling, and his myth is perfect for the whole — you know, it really ties into the African American folkloric tradition, which is rooted in stories and storytelling.

Chuck Reece: She also points to the Gothic storytelling that is part of so many Southern art forms.

Kimberly Mack: The whole thing with Southern Gothic is you're kind of making sense or trying to make sense of the senseless through narrative. And whether it's literature or even with music. If you think about music, its lyrics — a lot of the stuff that's considered Southern Gothic in lyrics — are doing a similar thing. You’re making, trying to make sense of tragedy. You know, the tragedy of chattel slavery, you know, the tragedy of the violence that came afterwards, the tragedy of racism and all the effects that it has.

Yeah, we do have great stories in country music. We do have great stories in folk music. … But with the blues you also do have the narrative that is responding to this legacy of enslavement and violence.

Chuck Reece: But in the 20th century, white blues fans and researchers tended to look away from that legacy. Their fascination with the mythology — It was like the shiny object they couldn’t look away from. It was easier for them to write about the romance they associated with people like Robert Johnson than to document the realities of his life. And that tendency is clear in the writings of Mack McCormick. We now have access to those writings. Although Biography of a Phantom was not publi shed during McCormick’s life, it did reach bookstores in 2024.

A few years after his death, McCormick’s daughter, Susannah Nix, decided to hand over her father’s entire archive — the Monster — to the Smithsonian. When it arrived in Washington in 2020, just as the COVID pandemic was taking hold, it became John Troutman’s job — and that of many of his colleagues — to dive into the 90 linear feet of McCormick’s Monster.

The version of Biography of a Phantom published in '24 does include 12 chapters — 181 pages — of McCormick’s own writing. The writing is insightful, and it is clear that the mythology and mystery around Robert Johnson absolutely enthralled McCormick. Let me read a brief passage, written in the '70s. Here, McCormick describes the result of the futile search for Johnson in '38, when Hammond wanted him to play Carnegie Hall.

In time word came back: Robert Johnson was dead. He’d been murdered. The record company people had learned that much and no more. The search for Johnson ended there, but in another sense it only began at that point, becoming a deeper search that continues to the present day. The stories regarding his death have taken innumerable forms: A kid whose passions got him killed. A youngster murdered by an evil woman. A poet who earned his songs by walking with the devil.

But Biography of a Phantom also contains a preface and an afterword — 39 total pages, written by the Smithsonian’s John Troutman. Troutman had to write those because inside the Monster, his team discovered that, as Mack McCormick obsessively chased his story about Robert Johnson, Mack made a few of his own deals with the devil.

Troutman says the Smithsonian team discovered more than a few contradictions and inconsistencies inside the Monster. Even some of McCormick’s own accounts conflicted with each other.

John Troutman: One of the interesting challenges that I had to navigate, when working on projects in that archive, was that discovery process of recognizing that these drafts of these stories that, in some cases, are completely antithetical to one another in terms of the facts and in terms of conversations and what things are said. And from there, as a historian, my goal is to try to figure out, "OK, where does it line up? Where do these stories line up and what is happening with the stories that don't add up?" And I didn't really have any guideposts along the way other than just to kind of sift through everything and piece that together.

Chuck Reece: In a single podcast episode, it would be impossible to tell the whole story of all the moves Mack McCormick made in his five decades of chasing Robert Johnson’s story. But his chase began around 1970 when he first visited Friars Point, Miss., a town Johnson calls out in his “Traveling Riverside Blues.”

MUSIC: Robert Johnson - "Traveling Riverside Blues"

“Best come on back to Friars Point, mama, and barrelhouse all night long.”

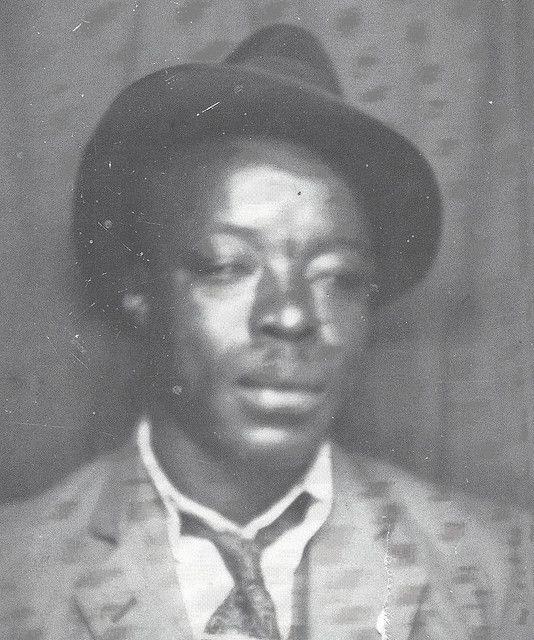

Chuck Reece: After picking up a few vague clues in Friars Point, McCormick searched for two more years before locating two of Johnson’s sisters — Carrie Thompson and Bessie Hines — who were living in Maryland. He interviewed them and they shared photographs of their brother.

John Troutman: One of the things that I found early on was two different sets of agreements between Mack and two of Johnson's sisters. They're dated the same date in 1972, in Churchton, Md., where he eventually kind of caught up with the sisters and started interviewing them and recording the interviews and everything. Both sets were signed by the sisters. One of the agreements was pretty short and just said that each sister gives him the right to share their stories for this book. And in turn, Mack would agree to do everything in his power to make sure that they are recognized as the heirs of their brother in terms of the estate, the Robert Johnson Estate. So this was the agreement that Mac made. The other agreement was much longer. It was on legal size paper and went over a page into the second page. And it very much specifies, on a much more granular level that — he wrote them a check as part of this agreement as well. And they specify he has rights to their stories, that he's paid for rights to all of these photographs to use however he sees fit.

Chuck Reece: Troutman and his team at the Smithsonian wondered why there were two separate contracts and — more particularly — why there were inconsistencies between them.

John Troutman: So why are there two different sets of agreements and how did this come about? How did it play out? There were cashed checks to the sisters, but the amounts were marked out. There are photocopies of the cashed checks, never found the originals. It seemed odd. They were on two different types of letterhead, different watermarks on the paper, but they were signed the same day in Maryland. Different typewriters too, in terms of the type set or the letter. The characters of the typewriters were different. So that was weird. And as I kind of continued to move into different areas of the archive, I found, well, that's when I learned about his arrest for forgery as a teenager.

Chuck Reece: When McCormick was young, his mother moved frequently from town to town, looking for work. Mack had fallen in love with the jazz music he heard on the radio, and became determined to make a living writing about music and doing research. When he was 19 years old, he got a gig writing for Down Beat. But the job paid very little. Mack was essentially living off handouts from his mother. Wanting to stop asking her for money, McCormick turned himself into a forger and cashed checks under six different names. And got busted.

After Troutman discovered McCormick’s teenage forgery conviction, he and his team dug once again into their study of the two conflicting agreements McCormick had made with Johnson’s sisters.

John Troutman: It became quite clear that the longer-form agreement was forged. It was faked and it was forged by Mack.

Chuck Reece: Why did McCormick forge that document? One reason is Mack’s own laziness. After McCormick located Robert Johnson’s sisters and signed the genuine contract with them, he had promised to stay in communication with them. But he waited 16 months before he called them again. During that time, one of the sisters, Bessie Hines, had taken ill, and the other, Carrie Thompson, had become responsible for her care. Under this new financial stress, Thompson worried about the photographs of her brother that she had given to McCormick. That’s why, when another blues researcher named Steve LaVere showed up at Carrie Thompson’s house about a year into those 16 months, she was happy to share with him another photograph she had discovered in McCormick’s absence. When McCormick finally called Carrie Thompson again, she told him about her meeting with LaVere. McCormick pleaded with her not to work with LaVere, but she no longer trusted McCormick.

This is where the legendary John Hammond, who by this time had discovered Bob Dylan, too, comes back into the story. Steve LaVere approached Hammond and pitched him a book and the chance to release Robert Johnson’s remaining recordings, along with Carrie Thompson’s photographs and stories. She didn’t trust LaVere much either, but at least he had Hammond and Columbia Records behind him, so she signed a deal with LaVere, giving him rights to the material with an agreement that she would get a portion of the royalties from the book and new record release.

John Troutman: When Mack learns that Steve LaVere has made agreements with the sisters ... well, with Carrie; I think her sister Bessie had already passed away — then Mack reaches out to John Hammond at Columbia, who's planning to release the box set in 1975 with the sisters' stories and with photographs and what have you from the family. And that's when Mack begins sending him threatening letters, quoting from the longer fake agreement that he had crafted.

Chuck Reece: Just so we’re clear here: Mack McCormick had forged a more detailed contract with Johnson’s sisters in an effort to threaten John Hammond with legal action if Columbia releases the remainder of Johnson’s music. Then, Hammond begins receiving more correspondence from people who say they have more information supporting McCormick’s claims. A Patricia Scott, who claimed to be Mack’s secretary. A Norris Stonecipher, who claimed to be his legal representative.

John Troutman: And then I find all this correspondence from folks like Norris Stonecipher, and these people representing Mack. I figure out that they're all fake aliases that Mac's using to write as an attorney to respond to the attorneys from Columbia. Mack's kind of in a panic state, basically trying to slow down and stop the release of the box set because he feels that he's entitled to tell these stories. And so that creates a 15-year hiatus.

Chuck Reece: Indeed, Columbia did not release Robert Johnson: the Complete Recordings until 1990. It won the Grammy Award for Best Historical Album, and it reached No. 80 on the Billboard 200 chart. But sadly, Carrie Thompson, the second Johnson sister with whom McCormick had made a deal, was already dead by then. She had passed away in 1983. So only one of Robert Johnson’s siblings, at that point, was still alive: his youngest sister, Annye Anderson.

After McCormick’s death in 2015, Mrs. Anderson began collaborating with the great Memphis music writer, Preston Lauterbach, on her own book about her brother. That book, Brother Robert: Growing Up With Robert Johnson, was published in 2020. At that time, Annye Anderson was 93 years old. And just after, the Smithsonian took possession of Mack McCormick’s monstrous archive. In her book, Mrs. Anderson details how the false promises of Mack McCormick and Steve LaVere affected her and her sisters. And she shares a letter she received from Carrie Thompson before she died. That letter says, “I wish I had never got into it at all. Just feel hopeless now, hate for the white man getting the benefit of what I should have, although according to God’s word the unjust won’t prosper.”

The Smithsonian is doing what it can to set things straight. At the request of Annye Anderson, the released version of McCormick's Biography of a Phantom does not contain the interviews McCormick did in the '70s with her sisters. And the museum is transferring the photographs they gave to McCormick to Mrs. Anderson.

John Troutman: Mack didn't live up to his end of the agreement in working to advocate for the sisters being the heirs of Johnson. So ultimately, when we were able to connect with Mrs. Anderson, I shared with her our plan to transfer these photographs. I told her about these interviews as well. She began sharing with me stories about — and some of them are in her book, Brother Robert, which was kind of this really remarkable chronicle of not only her family's history, but also of the history of these takers in their family's life of like Steve LaVere and Mack McCormick, who left the sisters with nothing. And they were living in poverty.

Chuck Reece: What can we learn from this? Well, that’s hard to say. But telling y’all this story, I have come to a conclusion of my own: That the next time I hear a story about somebody making a deal with the devil, I’ll be more likely to believe that the one telling the story is the one who made the deal.

CLOSING

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank John Troutman and his staff at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History for their help and cooperation in producing this episode. There is so much information in the book produced at the Smithsonian we could never dream of sharing all of it with you on this podcast. We encourage you to get your own copy of Biography of a Phantom. Also, our thanks go out to Dr. Kimberly Mack, whose book, Fictional Blues, is an absolute must not only for fans of blues music, but anyone who wants to learn more about how Southern culture just breeds mythology. And finally, we must thank Tinsley Ellis, a man who has played the blues with integrity for 40 years and who has finally recorded his first album of acoustic blues, no amplification, just like Robert Johnson did it 90 years ago. It’s called Naked Truth, and it is a fine listen. Speaking of listening: This has been Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of 20 stations around our state. Every week, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South magazine, which you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com.

Our producer and the composer of our theme music is Jake Cook. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without the support of wonderful people like GPB’s Bert Wesley Huffman and Sandy Malcolm and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length, dee-luxe episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.