Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: After the Deluge - Old Fort Revisited

Primary Content

Hurricane Helene devastated Old Fort, N.C., in 2024, but this small community's innovative economic plans, centered on outdoor recreation, are helping them rebuild stronger than ever. A tale of hope, unity, and determination in the face of disaster.

TRANSCRIPT:

INTRODUCTION:

Chuck Reece: Back in the 20th century, almost everybody in Old Fort, N.C., who wanted a job had a job. They could work in a textile mill owned by a company based in Teaneck, N.J. Or they could work at a furniture factory owned by a company from Danbury, Conn.

But both those mills both shut down.

[From episode Deluxe: Racial Unity Brings A Small Town Back to Life]

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty: We went from being a relatively vibrant economy where people could work, live and get services in the community that they lived in to a community where we were almost a — a dustbin.

Chuck Reece: That’s Stephanie Swepson-Twitty, and she’ll be back with us later.

Those dustbin stories were common when trade was globalizing in the late 20th century. The leaders of many small Southern towns thought the only answer was to search for other large companies that might replace those manufacturing jobs. For most, that was a losing strategy. But the people of Old Fort had a different strategy — a plan so audacious and stubbornly self-sufficient that we decided to make their story the very first episode of Salvation South Deluxe two years ago.

Here’s a quick summary. About 10 years ago, the leaders of Old Fort, Black and white alike, came together to build a plan — which by itself was an uncommon occurrence in the rural South. And when they did, they asked themselves a big, important question: how can we rebuild an economy that no giant company can take away from us? The people of Old Fort did have a huge asset: Their town sits on the edge of the Pisgah National Forest, 500,000 acres of protected land. So they envisioned building a 42-mile network of trails for hikers and mountain bikers that would connect Old Fort to the Blue Ridge Parkway, which runs right up the middle of the national forest and attracts more than 16 million tourists every year.

In the fall of 2023, when we finished our first show from Old Fort, 7 miles of that 42-mile network was done. The state had allocated $2.5 million dollars that would let them finish the full network by 2026, three years faster than the original target of 2029. Land was being set aside for affordable housing. An old furniture warehouse had been bought with plans to create a hub for homegrown startups. Hundreds of bikers and hikers and other outdoorsy folks were already flocking to Old Fort every weekend, and small businesses like a bike shop and a brewery and a bakery with CRAZY-good cinnamon rolls had sprung up to serve those visitors and the locals, too. Old Fort’s plan to rebuild its economy on outdoor recreation was working very well.

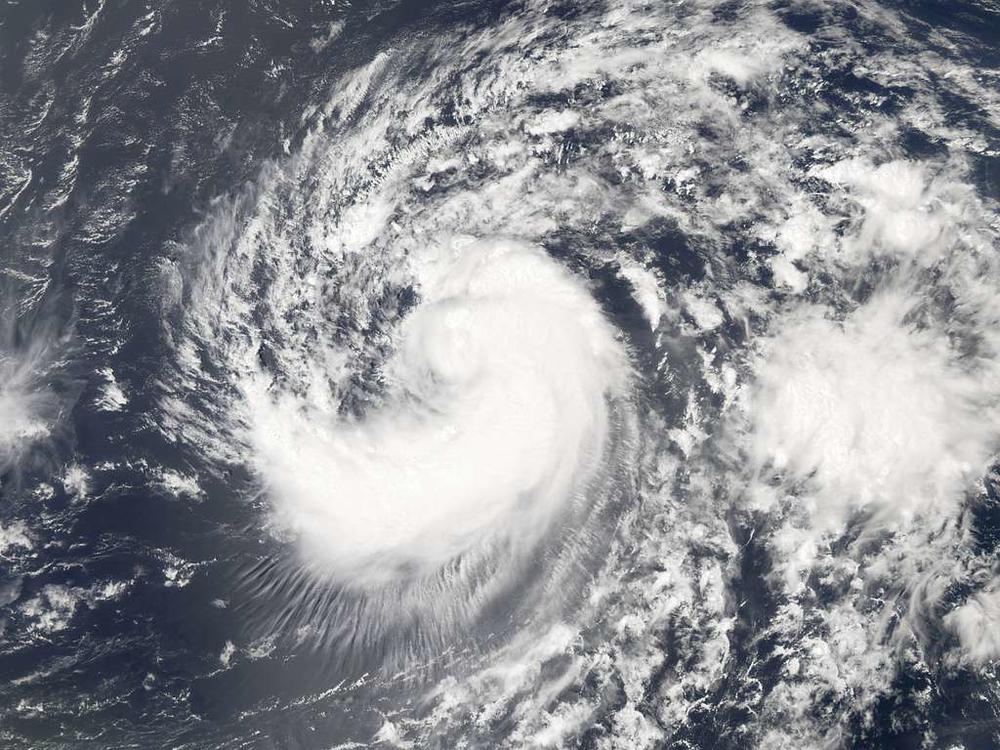

Then, in September of 2024, Hurricane Helene brought once-in-a-millenium floods to western North Carolina. The Catawba River, which runs right through the middle of downtown Old Fort, surged as high as 20 feet above its normal water level.

Chuck Reece: On our first trip here two years ago, I had met Jason McDougald. He is the executive director of Camp Grier, a beautiful summer camp just outside town. Since 1952, Camp Grier has been teaching kids from the second grade through the 12th grade outdoor skills every summer, and Jason has managed the camp for more than a decade.

He was also in the group of visionaries behind the trail network project.

Jason Mcdougald: The storm, it was kind of two waves. There is like this kind of — tropical depression or whatever you call it, that came through first. And, you know, that was Wednesday. And so when we woke up on Thursday ... I’d never seen flooding, you know, to that level here at camp…in the 11 years since I've been here.

Chuck Reece: After a while, he managed to hike into town.

Jason Mcdougald: When I got in there, you know, and I saw what condition Old Fort was in…. I mean, there was a foot of mud downtown. Like the natural gas smell was just something I'll never forget. You know, just huge gas leaks. People in town, you know, in their bare feet and housecoats, you know, basically what they had on when their home washed away, were just kind of wandering around in town, kind of shell-shocked. And it was, you know, no communication. Cell towers were down, fiber was cut, roads were missing. Railroad tracks were suspended, you know, in mid-air. And it just looked like it was a disaster zone.

Chuck Reece: I had a million questions. Would Old Fort’s grand plans survive? Would they have to start over from scratch? I wanted answers, so, more than five months after the floods, I headed back to this little town of 900 people in western North Carolina.

I’ll tell you what I saw and heard. I think you might be surprised.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed hoping to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

THEME MUSIC OUT

ACT ONE

Chuck Reece: Welcome to Old Fort. That soothing sound you hear behind me is Jarrett Creek. I’m standing in the driveway of the same house I stayed in two years ago. Back then, there was about 20 feet of green grass between the driveway and the creek bank. Today, that lawn is gone. So is half the driveway, thanks to Hurricane Helene.

Chuck Reece: Helene first made landfall in Florida at 11:10 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 26. By then, the ground here in Old Fort was already soaked. A week before, two and a half inches of rain had fallen, according to National Weather Service data. On Wednesday the 25th, another 1.1 inches fell and it rained all night. By the time Helene hit Florida on the night of the 26th, another three and a half inches had fallen on Old Fort.

Jason Mcdougald: When we woke up on Thursday, like already … I'd never seen flooding … to that level here at camp. You know, in the 11 years since I've been here. … The water was already over our bridges going into camp. ... That was when the hurricane was still, you know, off the coast. And so that morning was kind of where I thought like, "OK, this is going to be bad."

Chuck Reece: A few guests for an already scheduled weekend retreat were arriving, but Jason and his camp staff decided to ask them to head home while they could. The staff headed home, too. Only Jason stayed at Camp Grier, hoping to get some sleep in the director’s house, which sits about a 100 feet from Jarrett Creek by the gate into the camp.

Jason Mcdougald: The storm kind of hit in the evening. And I think our power … we lost power at like 3 or 4 in the morning. It was hard to sleep that night because it was, you know, windy and it was just pouring rain. And so I would get my truck and just kind of ride up the camp road to the first bridge and just see, you know, how it was. All those creeks and streams came right back out and the water was back over the bridges.

Chuck Reece: The rain never stopped that night.

Jason Mcdougald: Friday morning I got up … about 6 or 7. … I had packed a bag the night before just in case I had to get out. So I just got up and made coffee and, you know, was just looking out the window, really, watching it rain. About 8, 8:30, I heard a crack out our back. Back of the house, and a tree had fallen and it came. Basically cut the director's house in half while I was in it. And so that opened a huge hole in the house and just started pouring in rain.

Chuck Reece: Jarrett Creek typically runs under Highway 70 then flows into Mill Creek, which runs parallel to the highway. After the tree fell, Jason grabbed his bag and got in his truck. He sat in the driveway of the director’s house and watched Jarrett Creek rise so high it overflowed the highway. Then he watched Mill Creek rise until it submerged the railroad tracks.

Jason Mcdougald: Over the next two hours, from like 8 to 10, you know, you could really see the water coming out. I mean, this was the heart of the storm. Right around 10:00, there must have been some kind of debris jam on some of the bridges because the water really started to come up quickly. In about 30 minutes, it had risen several feet, 4 or 5 feet. And then once — something happened, that debris jam must have broken loose. ... Because as soon as that water, as quickly as it came up, it went down. And so I think that — that wall of water is what took out, you know, a lot of homes and businesses and in town, you know, downstream from it.

Chuck Reece: When we first visited Old Fort in 2023, we met Wendy Lewis, the proprietor of Gogo’s Cinnamon Rolls, the home of those crazy-good treats I mentioned earlier. Wendy’s husband Jerry pastors Grace Community Church, which sits halfway between Old Fort and the town of Marion, 10 miles east. Where they live in Old Fort sits on the north side — the high side of the Catawba River. Their basement flooded, but their house suffered no other damage. So Jerry and Wendy got in their truck to see what was going on in the town.

Jerry Lewis: So we drove over to where you could look out on the middle of town. And it was it was unbelievable. Cars were floating.

Jason Mcdougald: I guess it was about 11 or 12, you know, the storm kind of started to pass. And so then the first thing I did — I still couldn't walk up our road because it was still kind of a river. So I just kind of bushwhacked up the ridge to get into camp.

Chuck Reece: Camp Grier was founded 70 years ago, on land about a 100 feet higher than Highway 70. Up at the camp, there is a dam on Jarrett Creek that creates a lake, where summer campers now swim and paddle. The dam was holding fast.

Jason Mcdougald: I really couldn't believe my eyes when I got up there. I just I was really shocked by how little damage Camp sustained. All of our buildings were OK. We had a couple of trees down on the road and that kind of thing. And obviously, you know, trees on power lines and stuff. But like, our buildings, like our commercial kitchen and all of our lodges, you know, everything was fine. And so I was just like, thank goodness.

Chuck Reece: This was news Jason wanted to share, but the only method of communication available was literal word of mouth.

Jason Mcdougald: So I decided to come back to Camp and kinda hunker down here for that first day. It was kind of like, OK, survival. I was, you know, assessing what's good on the ship, you know, it's "OK, we got this freezer full of food. We've got some generators up at Camp," you know, very heavily resourced. And so from that point, it was just trying to use what we had, to conserve what we had and working to rebuild our roads so we could get in and out.

Chuck Reece: The rain continued to fall all day. By Saturday morning, another 6 inches had dropped, and it wasn’t letting up.

With their home safe but Gogo’s shut down, Jerry and Wendy Lewis wanted to find ways to help their neighbors. Jerry decided to head for the McDowell County Emergency Operations Center over in Marion to see how he could pitch in. But the bridge on Highway 70 to Marion was out. His only hope was to cross the bridge over the Catawba in downtown Old Fort so he could reach Interstate 40 toward Marion. The bridge was damaged and closed, but it was passable. Jerry went looking for Old Fort’s mayor at the time, Pam Snypes, hoping she would give him permission to cross it.

He found her in the middle of town, directing traffic.

Jerry Lewis: I ask her if she would let me go across one of the bridges and go get us some help. And she agreed.

Chuck Reece: When Jerry arrived at the Emergency Operations Center in Marion, he walked in just as Will Kehler, the county’s emergency services director, was beginning a meeting with his team of responders.

Jerry Lewis: I've known Will for years. And when I walked in, it was the first what they call control group meeting. … we all we were all introducing ourselves. I just walked really in on that meeting. And when they got to me, Will said, “And Jerry will be leading our humanitarian response for the county.” I went, “Wow.” And so immediately, everything in my world shifted.

Chuck Reece: He did not refuse this emergency appointment.

Jerry Lewis: He gave me a team and he said, “Jerry, we have a warehouse and we will not have a second disaster on top of the first. We need water, we need food. And the state is out. This is their third storm. We have three simultaneous responses by the state. They have already informed me they have no water. They have no food to send our way, no MREs, no water.”

Chuck Reece: So Jerry, who has pastored Grace Community Church for 25 years, turned to other churches in North Carolina for help.

Jerry Lewis: So thankfully, just what, two, three weeks prior I had been — I'd led a meeting of pastors of the largest churches in the state in our denomination. I just jumped on a text to them and I said, "We need help and we need it now. We have no water. We have no food. We have no power." … And so these … they pastor very large churches. So that was on a Saturday. They put word out to their people: “Don’t show up tomorrow without water, food and diapers.” ... We had a great team.

Chuck Reece: The county’s superintendent of schools and the president of McDowell Tech Community College also showed up to pledge their resources.

Jerry Lewis: And we got to work.

Chuck Reece: With no electricity, the team’s first priority became getting help to people whose medical conditions required power: seniors and others who needed oxygen support and people with kidney disease who required dialysis.

Jerry Lewis: We had to have an O2 shelter. We had 50 people that if they didn't get to power, they could die. These are older people on oxygen and there was no power. And so by 7 p.m. we had it set up, completely powered, ready to go.

We had 50 people that had to get to Hickory for dialysis. So part of my job was to, by Sunday morning, they had to be on their way.

Chuck Reece: That happened, too.

Jerry Lewis: Wendy, we knew we couldn't open the business. We had product ready to sell. So she grabbed product. She joined me at the EOC and she started cooking breakfast and lunch for 200 people a day. So —

Chuck Reece: Wow.

Jerry Lewis: So what she and I did for the next two weeks was — it was a complete redirect in our lives, everything.

Chuck Reece: Jerry and his team had access to three warehouses they could use to store supplies and quickly move them out to residents who needed them.

Jerry Lewis: By Sunday evening we had our first semi-roll-in of supplies. We had 150 volunteers. We set up an inventoried warehouse with full, complete everything you would imagine in a warehouse. The forklifts, everything. Everything organized, palletized.

Chuck Reece: Meanwhile, at Camp Grier, Jason McDougald and his staff were determined to turn the camp into a refuge for displaced residents.

Jason Mcdougald: It took a couple of days just kind of to get oriented, you know, like we we had, you know, some generators here at camp and we were able to get those hooked up to our well, so we could have running water. We were able to get another generator hooked up to our ice machine, because we were really wanting to make sure that we preserved that food that we had. Our kitchen staff ... they really thought ahead because they had packed a bunch of coolers with ice prior to the storm, anticipating that we'd would lose power. And so that was, you know, in our walk-in freezer. And so that was great.

So for a couple of days, it was really just us, you know, really through the weekend, like Friday to Monday morning was just us working to stabilize, you know, the systems. Our maintenance staff got back and were able to get into our machines and start pushing our road back to the bridge so that we could get access.

After a couple of days, we were able to get, you know, our road repaired, you know, enough that we could get in and out with vehicles and UTVS. And then we were fortunate enough to get a StarLink from someone. And so we were able to quickly get communications and we started working on a larger generator.

Chuck Reece: Jason’s stepfather, who lives in Atlanta, called some friends who own a company that supplies equipment to utility companies.

Jason Mcdougald: They were able to put one of their staff on finding us a generator and they were able to source one and get it up here that week. And so by the end of the week, we had, basically, a hospital generator … running the main camp, which is amazing. And we ran off that generator power for about a month.

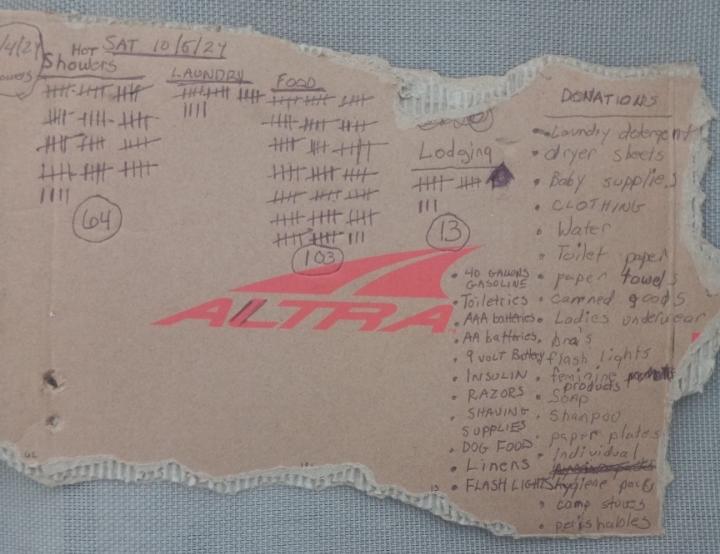

Chuck Reece: Within days, Camp Grier was feeding displaced residents and providing a clean place for them to take hot showers and do laundry. Communications were still out, though.

Jason Mcdougald: It was back to the analog days. I mean, we we painted a four-by sheet of plywood and stuck it in downtown Old Fort with an arrow on it.

Chuck Reece: What did it say?

Jason Mcdougald: It was like “Food, Showers, This Way.” It was really hard to get the word out to folks, but that really worked well.

Jason Mcdougald: We were doing, you know, a little over a 100 meals a day for our neighbors and then probably about 50 showers a day for neighbors and, you know, 20 to 30 loads of laundry a day. … We pretty much operated in that mode for all of October and November. So, yeah, about 60 days of just really, you know, fast-paced relief.

Chuck Reece: But not everyone who was dirty and hungry could get to Camp Grier. Jerry Lewis remembers one night that week at the Emergency Operations Center when a little incorrect planning resulted in the preparation of hundreds of meals, but no one to feed them to.

Jerry Lewis: I speak Spanish fluently. So when I went out that night, pitch dark, I go into this Spanish neighborhood, a trailer park. I got my cellphone. I said, “Lord, just give me somebody. Give me one person.” I had the back of my pickup truck full of food. House No. 3, out comes this guy. Told him what I'm doing. He said, “I know all the people who need food.” He jumped in the truck. Here we go. House to house. He said, “Let's stop here. Let's stop there.”

Chuck Reece: The need Jerry encountered that night was deeper than he’d anticipated.

Jerry Lewis: We found a family that had been rationing a granola bar since Friday.

Chuck Reece: You heard that right. One granola bar, portioned out bit by bit over several days.

Jerry Lewis: When we run out of food, he said, “You don't have any more?” I said, “No.” He said, “But look at all those children on that porch. They haven't eaten. They haven't eaten.” And I said, “All right. Tomorrow we serve lunch. There will be an entire delivery crew here. They will deliver food to everybody.”

Chuck Reece: With the help of many volunteers, Jerry and his team made good on their promise.

Jerry Lewis: We got to them with hot food. We found another family. And when we knocked on her door, she was crying because she said, “I just told my kids I've used every bit of food we have. And we're out.” And we brought her food. Enough hot meals for every person in her family.

Chuck Reece: This was not a one-night miracle. With the supplies they had warehoused, the people of McDowell County mounted a well-organized operation that fed people for weeks.

Jerry Lewis: When our people showed up, we had hundreds of volunteers, some of them who had lost everything, handing out food to people. That's just how it happened. And it was — it was amazing, those kinds of things that happened. And nobody cared who got the credit. That was the cool piece. We were just trying to get it done.

Chuck Reece: We’ll be back after this short break to talk about how Old Fort is also rising to meet the longer-term challenges brought by Hurricane Helene.

MIDROLL BREAK

ACT TWO

Chuck Reece: Welcome back to Salvation South Deluxe.

SOUND: Jarrett Creek

Chuck Reece: Here we are again on the bank of Jarrett Creek. Earlier I mentioned how the creek washed out the driveway next to it. It’ll cost about $30,000 to repair, I’m told. But that is barely a speck of dust against the $59 billion in damage Hurricane Helene dropped on this state, according to the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management.

Jarrett Creek flows into Mill Creek, on the other side of Old U.S. Highway Seventy from where I’m standing. And a Norfolk Southern rail line parallels Mill Creek. The creeks merged on that day in September and roared toward downtown Old Fort where Mill Creek flows into the Catawba River, the rail line that ran beside Mill Creek was destroyed. Not just in one place but for miles. The tracks are twisted like pretzels. Houses alongside the railroad and into downtown Old Fort were destroyed. The cataclysmic flooding destroyed more than 50 homes and damaged about a 175 more in and near the town. We’ll post many photographs of the damage on SalvationSouth.com along with this episode.

Across the whole of western North Carolina, 560 homes were destroyed, and more than 2,000 were damaged.

Chuck Reece: Townfolk in Old Fort call it “the apocalypse.”

They are devastated still. And they will feel that way, I expect, for a long time to come. But when the apocalypse came, they held fast to the most important rule for living life: They loved their neighbors. They made sure people were warm and dry, that they were fed and sheltered, that they could take a shower and wash the mud out of their clothes. And they kept doing it for about two months.

Philip Bell: When something like this happens and you see people drop everything to come to help and to lend a hand and to be selfless, it gives you hope, right? And hope means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. But for me, that's hope that generally we all want to see others do better.

Chuck Reece: Philip Bell is the project manager of the Old Fort Strong Fund. While Camp Grier was still feeding people, the nonprofit that runs it established the Old Fort Strong Fund to help people who had lost their homes and businesses rebound quickly.

They immediately turned to outdoor recreation — their new economy’s bread and butter — to raise money that would go directly into the hands of Old Fort residents so they could rebuild their homes and repair their businesses. They announced the Old Fort Strong Endurance Festival and invited mountain bikers and trail runners either to ride or run a series of loop trails 11 weeks after Helene.

Chuck Reece: There would be 200 spots for mountain bikers and 200 for runners. To sign up, you had to commit to raise at least $1,500 dollars. If every available spot was filled and each person raised the minimum, it would produce $600,000 for the fund.

The slots for runners sold out within three days and the bicycle slots within a week and a half. By Sunday morning, when the last of the 24-hour runners and riders straggled in, they had raised $950,000 dollars. About six weeks later, when I interviewed Philip, the total was up to about $1.1 million. And more than $400,000 of that was already committed to help people replace cars, find housing, and make repairs.

The need is still greater than the Old Fort Strong Fund can provide.

Philip Bell: The plan is to keep the fund going. You know, we're applying for grants. We're working with foundations and leveraging our network to continue to try to add to that number and, yeah, get more money out the door to families in need.

Chuck Reece: More than 100 people have applied to the fund for help so far, and more keep coming. Philip Bell talks to every one of them, so he can understand what they need and get it to them.

Philip Bell: I have one single dad, right? With a 12-year-old daughter. And he was living downtown. And, you know, the water came through and essentially washed his home away. … A mother of two, you know, is living in a camper right now with a dog and her boy and her daughter: 7 and 5. Their car washed away. Their house washed away. So as a fund, we — we're helping with cars as well. helping her get a car to replace hers so she can get to and from work and take her child to day care.

Chuck Reece: Philip has become a logistical wizard of sorts.

Philip Bell: No one gets turned away. … It's just the bottleneck of, you know, communicating with vendors, contractors, writing the right checks and going to Lowe's. And I'm working with credit unions and things like that that just kind of hold it up.

I've been boots on the ground here, Chuck. … There's an immeasurable need that's well above what we've raised so far.

Chuck Reece: Philip has no plans for a job change anytime soon. He will keep working to provide what people need right now.

But what will the people of Old Fort need a decade from now?

When Salvation South told the story of this town in 2023, the focus was on getting the funding to build that 42-mile network of trails. If we build it, they believed, the hikers and mountain bikers would come — by the thousands. Old Fort wanted to make itself “the next great trail town.” That phrase comes from one of the two major projects Old Fort’s coalition of big thinkers were planning, projects that would ensure a sustainable economy around outdoor recreation.

One is called the Catawba Vale Innovation Market, the transformation of a 60,000-square-foot former furniture warehouse. The building sits in the middle of downtown and will become a home for start-up manufacturing operations. A furniture manufacturer is already slated to start making its products there. It will also house the McDowell Chamber of Commerce, a digital film studio, and an event and hospitality center. Plus a retail food operation on the ground level.

Chuck Reece: The second is called Grier Village. If the Innovation Market is designed to incubate the small businesses needed to serve an outdoor recreation economy, then Grier Village is meant to be that economy's central destination. It will welcome and house and feed — and even brew beer for — everyone who shows up with a mountain bike, trail-running shoes, or a pair of hiking boots.

On 800 acres adjacent to the existing summer camp, Grier Village will include affordable housing for the local workforce. The town lacks a hotel, so the plans include short-term rental cabins for tourists. Land that will support sustainable farming practices. Locations for retail and other small businesses.

McDowell Tech Community College has added a certificate program in trail construction and sustainability, with free tuition for anyone who lives in the county. Grier Village will have classroom spaces and housing for students.

Jason Mcdougald: There's going to be three different products. So one product ... is basically straight visitor lodging. You know, we don't have a hotel; we need places for people to come in to stay. So these are — there's plans for up to 10, but we're starting out with five cabins. Five will be built in Phase 1 and these will be five-bedroom, five-baths. Everybody will have an en suite kind of setup.

Chuck Reece: The second part will cater to the local workforce, or those who aspire to be part of it.

Jason Mcdougald: So like imagine, you know, groups coming in to Old Fort to take classes with the trail school. ... So these are young adults who are 18 to 24 who want to get into the outdoor rec economy. They're taking classes at the community college, working part time and living with us. So below market rate, student housing.

Chuck Reece: The third piece will greet people as they arrive to hit the trails.

Jason Mcdougald: This is where you go to check in, retail, taproom, bike shop and coffee shop, amphitheater. ... There's going to be some long-term, below-the-market-rate rentals for ... seasonal Forest Service crews or people who just need below market rate rentals that are here working on public lands or you're working for us or whatever.

Chuck Reece: My assumption as I headed to Old Fort for this visit was that these projects would be delayed thanks to Hurricane Helene. Both of the major construction sites for Grier Village sit directly across the highway from the devastation of the flooding along Mill Creek, so I didn’t expect to see cranes and bulldozers and excavators running full speed when I returned to Old Fort.

But they were.

Jason McDougald said he expects cabin rentals to begin in early '26, with other components of the project opening later that year.

The Catawba Vale Innovation Hub is a project of Eagle Market Streets Development Corporation. That's the nonprofit economic-development organization that Stephanie Swepson-Twitty has run for decades. When I asked how much delay she expected, she told me Helene had actually accelerated her timeline. She expects the Innovation Hub renovation to begin, at the latest, in January of 2026, and for the building to be fully leased by December of '27.

But Stephanie was also proud of how the Innovation Hub building, which her nonprofit bought in 2020, was critical to the relief effort in the immediate aftermath of Helene.

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty: About 3/8 inches of silt is the only thing that happened to this massive structure on the — on the ground level there. It took the National Guard roughly about nine hours of work to — to clean up our building, whereas our neighbors to the left and neighbors to the right of us, it took weeks for them to be back online.

Chuck Reece: America’s biggest producer of hardwood plywood and veneers, Columbia Forest Products, is based in Greensboro, N.C., and has a manufacturing plant in Old Fort. Helene recovery efforts dramatically Increased the demand for Columbia’s products, but it also damaged its storage facility.

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty: The town came to Eagle and said, "Look, Columbia Forest Products needs to get back to the business of producing wood panels and they need their warehouse space. But we still have tremendous emergency disaster relief products and we need to move those products. Will you support us?" There was no question in my mind that we would not do that.

Chuck Reece: Columbia started moving products into the Innovation Market building, and in the process, the building found itself with a new nickname.

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty: The running joke is we've started calling it Noah's Little Ark. It’s sitting there, even in the midst of all of this decimation to the left and the right of it.

Chuck Reece: Here is what I believe after this second visit to Old Fort. Almost a decade ago, Old Fort’s people came together in an inclusive way to envision a new kind of economy for their town. Because they did that, then worked hard, very hard, to do the detailed planning and pull together the needed resources, Old Fort will surely come back faster and stronger than many other rural towns in western North Carolina.

Helene may have dashed their spirits for a while, but because of the work they were already doing, it did not dash their hopes.

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty: I think that our momentum — our emotional momentum, about how we work going forward as a community to build this — my words — "magnanimous economic engine" that was going to drive us into the 21st and post-21st century got a little dull. As we walked the streets of Old Fort and saw perpetually days on end the debris and carnage left in the wake of Helene, it was really hard to think about all of that vibrancy that we had envisioned for outdoor recreation and — and activity that we were looking to spur this economy.

Chuck Reece: But they are finding some salvation by diving back into the work.

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty: That is why I've been telling all my teammates, “Eye on the prize, y'all. Eye on the prize. We got a building to build. Let's build that building. Keep our eye on the prize.”

CONCLUSION

Chuck Reece: When 2026 comes around, Salvation South plans to head back to Old Fort, North Carolina. We want to do annual progress reports because we find ourselves in a unique position. By covering Old Fort over the long term, a town that could become a model for rural economic development in the South, we hope to provide some inspiration for the leaders of other small towns in the South as they face their own economic challenges.

We have many people to thank for their help and cooperation in producing this episode. Jerry and Wendy Lewis, who are, respectively, the pastor of Grace Community Church and the proprietor of Gogo’s Cinnamon Rolls. Gogo’s first reopened three weeks after Helene, and now, thanks to a brand-new temporary bridge opening on Highway 70, it's back to its old ways. That means although its official closing time is 4 p.m. every day, you’re likely to see the “Sold Out” sign appear hours before that. But if you get there in the morning, you’ll be sure to get something delicious to eat and a broad smile from Wendy. And don’t be surprised if you see a few tears in the eyes of the Gogo’s pre-Helene regulars as they return.

Wendy Lewis: One in particular, it was two state troopers who came in, I'd never seen them before. And I just walked in and they said, “We keep coming in because of the smile. Y'all all are just smiling and we just keep coming in because everywhere we go, it's just, you know, people have the long faces.” And I'm like, “Well, right now that's really all that we can give is smiles.”

Chuck Reece: And, of course, those crazy-good cinnamon rolls.

We must also thank Philip Bell, the project manager of the Old Fort Strong Fund. Also, Stephanie Swepson-Twitty, the CEO of Eagle Market Streets Development, which for 30 years has worked to increase economic opportunity for disenfranchised people in North Carolina. And last but certainly not least, we thank Camp Grier executive director Jason McDougald, who spent hours making sure we got a close look at the damage Helene did not only in Old Fort, but across all of McDowell County, and his wife, Ellen McDougald, whose hospitality and jokes make every visit a genuine delight.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of 20 stations around our state. Every Wednesday, we add a new 3-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com. That’s where you can also see Stacy Reece’s photographs of the damage — and the recovery — in Old Fort and McDowell County and in parts of Asheville.

Our producer is Jake Cook, who also composed our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without wonderful people like GPB’s Bert Wesley Huffman, Sandy Malcolm, and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.