Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: A Trip To Affrilachia

Primary Content

Discover how the Affrilachia movement is redefining the narrative of the Appalachian region, challenging stereotypes and embracing diversity. From poetry to visual art, hear the stories of those who are reclaiming their space in this often-overlooked corner of America.

TRANSCRIPT:

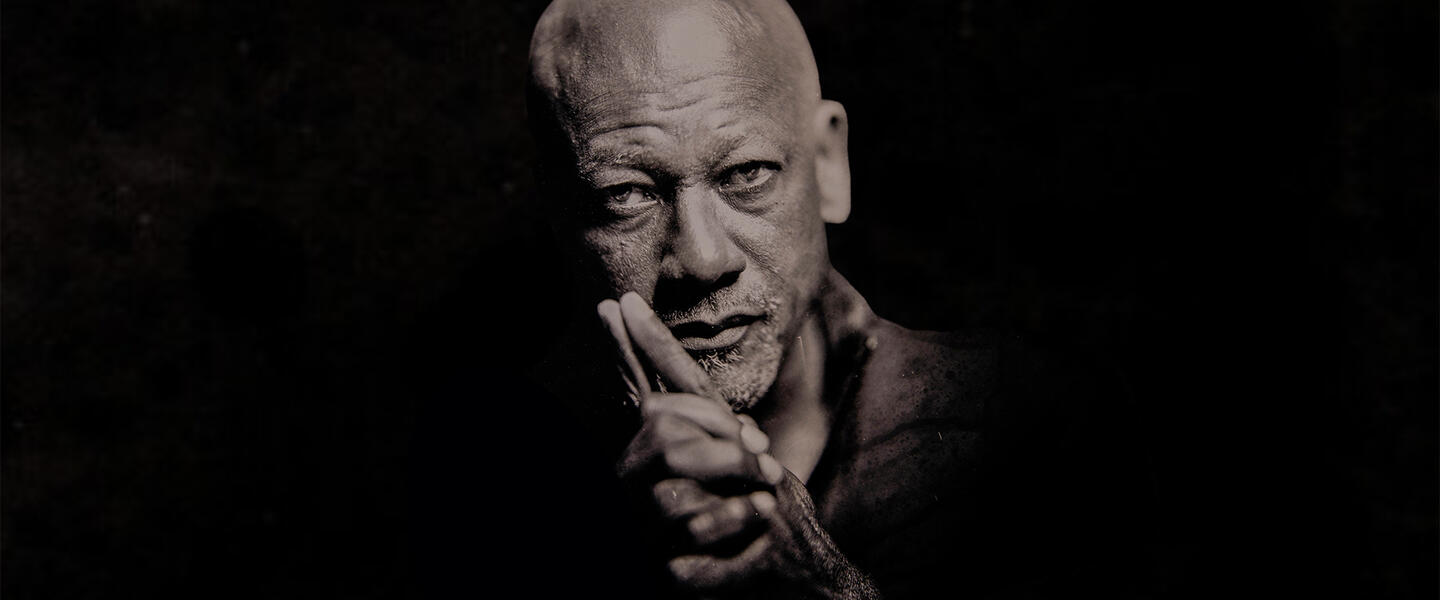

Frank X. Walker: I remember being in Washington state on a college campus. And there was a young man who raised his hand and asked if there were other people who were Black and who lived in Kentucky other than me, and I'm looking at him going, “I don't even understand where the question comes from.”

Chuck Reece: Frank X. Walker was born and raised in Danville, Ky. The year of his birth was 1961. Back then, roughly 9,000 people lived in Danville. And nearly a thousand of those folks were Black like Frank. Frank Sr. and Faith Walker lived in public housing there when they welcomed baby Frank into this world. He was the second of the 11 children they would eventually have.

Today, Frank X. Walker is a professor at the University of Kentucky, and his position often has him traveling to speak or read on other college campuses. And that’s how he wound up in Washington state on that day when a young man asked him if he was the only Black person in Kentucky.

Frank X. Walker: Then as we as we moved through the exchange, I understood that he had never been to Kentucky. He believed that The Beverly Hillbillies, The Dukes of Hazzard, The Andy Griffith Show, the movie Deliverance, that that was Kentucky. And Kentucky Fried Chicken. But, you know, even with the chicken, there was a white man on the box. In his head, in his full, you know, file for Kentucky fed to him by mass media, it was an all-white space.

Chuck Reece: Well, actually, Deliverance was set in the part of Appalachia where I grew up, in North Georgia. The mountains are smaller than the ones 350 miles north, where Frank grew up. But Appalachia still.

Even today, though, if you go to YouTube and search for the word "Appalachia," you can scroll all the way to the bottom and not see a Black face. In the broad American imagination, it seems the word "Appalachia" still translates to poor, uneducated, and white. Frank remembers an event in the 1990s that promised to showcase Appalachia’s greatest writers. They would read to a crowd of a thousand at the grand Lexington Opera House, a gorgeous venue built in 1886.

Frank X. Walker: Originally billed as the best writers in Kentucky. You know, the Appalachian, you know, writers. And then they added a woman of color, Nikki Finney, who at the time was living in California.

Chuck Reece: Finney is a National Book Award-winning Southern poet who spent two decades on the University of Kentucky faculty.

Frank X. Walker: They changed the name of the reading, the subheading and all the marketing. And they took “Appalachia” out of the title.

Chuck Reece: Now, you might be asking yourself why the addition of a Black writer would necessitate the removal of the word Appalachia from this event’s title. Frank wondered the same thing.

Frank X. Walker: That evening, I was home and I was just wrestling with this idea of why Nikki Finney's inclusion necessitated the changing of the name. So I just looked up Appalachia, in the dictionary. The dictionary I had at the time said Appalachians were “white residents of the mountainous regions of Appalachia.” And I was stunned. In that — in that moment, you know, recognizing that given my travels, there were nonwhite people who lived in the same geographical space. And if you had to be white to be Appalachian, what were you if you weren't white?

Chuck Reece: So Frank took up his pen.

Frank X. Walker: I go to the page to ask questions, you know, and if I'm lucky, I'll get an answer back. And I'm writing, trying to actually interrogate what I felt like and understood. My friends who were Appalachian and fit the definition, and my friends who did not fit the definition, what they had in common of, you know, oral traditions, love of music, food, family, religion, front porches.

Chuck Reece: And then a word came to Frank. A word no one had ever uttered before. A word that would change forever how Black people from the Appalachian mountains look at themselves.

Today, on Salvation South Deluxe, we’re going to take you to a place in the South that some of you will know well — and that some of you have never even heard of.

A place called Affrilachia.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed. Here on Deluxe, we bring the hidden parts of the Southern story into the light, and let you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

THEME MUSIC OUT

SCENE ONE

Frank X. Walker reading "Affrilachia":

thoroughbred racing

and hee haw

are burdensome images

for kentucky sons

venturing beyond the mason-dixon

anywhere in appalachia

is about as far

as you could get

from our house

in the projects

yet

a mutual appreciation

for fresh greens

and cornbread

an almost heroic notion

of family

and porches

makes us kinfolk

somehow but having never ridden

bareback

or sidesaddle

and being inexperienced

at cutting

hanging

or chewing tobacco

yet still feeling

complete and proud to say

that some of the bluegrass

is black

enough to know

that being ‘colored’ and all

is generally lost

somewhere between

the dukes of hazzard

and the beverly hillbillies

but

if you think

makin’ ’shine from corn

is as hard as kentucky coal

imagine being

an Affrilachian

poet

Chuck Reece: "Affrilachia" was the word Frank came up with that night three decades ago. And the poem of the same name, which you just heard him read, came to him along with the word.

Frank X. Walker: I took it to my writing group the following week. We met every Monday. And I — when it was my turn, I read through the poem. And they let me finish and then they made me repeat it again just so they could hear the word, because they'd never heard the word before. I hadn't either, you know. I wasn't sure that I had invented it. You know, it just seemed like the right word to use. So I did, and they loved the word so much. We agreed that evening to name ourselves the Affrilachian Poets.

Chuck Reece: In the year 2000, Frank X Walker’s first collection of poetry, also named Affrilachia, was published. Since then, he has published eleven more collections of poetry. In 2013, he was named the poet laureate of Kentucky, a position he held for two years.

The Affrilachian Poets Collective, formed on that night, is now the longest continuously running writing group for African Americans in this nation. For a quarter-century, the Affrilachian Poets, who currently number about 50, have nurtured the careers of many writers, and Walker himself has become one of the most lauded American poets working today. But the value of the word itself has arguably grown beyond the work of the poets’ collective and Frank’s own writing.

Frank X. Walker: And the word … it kind of gained energy and steam, as we did as a collective. Having a name encouraged us to be more organized and start having events in public and to start reading publicly. And from there, we wanted to be published and start making our own chapbooks and submitting to journals. And, you know, 35 years later, most of that group has multiple books in print, are teaching at universities. This Affrilachian movement moved beyond this original intention and became an opportunity to force people to look at Appalachia in a new way and acknowledge that it was more diverse than the caricature of the region suggested.

And so part of my, you know, my privilege over these last three decades-plus has been to to kind of spread the gospel, to talk about the region while developing and growing as a poet and writer and academic, and traveling, you know, storyteller. You know, it's been a joy to kind of celebrate the fact that there is diversity in the region, you know. It's not everywhere, you know, but it's not a homogeneous all-white space that people try to make it seem.

Chuck Reece: You might at this point be asking, how much money has Frank X. Walker made off this word Affrilachia? But he chose long ago not to turn it into a trademark or copyright it.

Frank X. Walker: Why didn't I trademark the word? And my simple answer was I was the first person to use it. You know, most people agree that I created it. But I never felt like I owned it.

I remember I got a piece of correspondence from a woman in — I think she was somewhere in Arizona. She wrote me this long letter on legal paper, longhand. She was in her 80s. And she wrote me this letter just to say that she was born in Appalachia, in Virginia. And until she saw that word "Affrilachia," she never felt like she could claim the space she was born in. But as an older Black woman who grew up listening to jazz but lived in the mountains and who grew up, you know, with a different set of heroes than, you know, were generally associated with the region, that she didn't feel like that it was hers. And everything that she was reading connected to the word just made her feel more at home. And so she just wrote, you know, in three pages to express her gratitude and thanks for the creation of a word that allowed her to claim the dirt she was born in. And I thought that was — that's a paycheck right there.

Chuck Reece: Frank X. Walker’s choice to let the word he created be free, to let other Black natives of the mountain South use it to fuel their own aspirations, has had a broad impact.

After this break, Salvation South Deluxe will introduce you another Affrilachian — a woman who, over the last 15 years, has used that wonderful word to celebrate the extraordinary creativity of Black mountain folks.

MIDROLL BREAK

SCENE TWO

Chuck Reece: Despite the fact that I am, myself, Appalachian and proud of it, and despite the fact that I have known for decades that African American people lived all up and down that great mountain range, I have to confess that I had never heard the magic word Affrilachia until the late Teens.

That was when I met a woman from Toccoa, Ga., named Marie T. Cochran.

Marie T. Cochran: I was watching Hee Haw and Soul Train at the same time and loving them. I had a crush on Michael Evans and John Boy at the same time.

Chuck Reece: She was simultaneously a product of Black culture and Appalachian culture. She knew, like Frank told us in his poem, that …

Frank X. Walker reading "Affrilachia" :

a mutual appreciation for fresh greens and cornbread an almost heroic notion of family and porches makes us kinfolk somehow

Chuck Reece: Marie is a visual artist. For decades now, she has created mixed-media installations and public art projects that celebrate Black life in the South. Back in 1996, when Atlanta hosted the Olympic Games, she and Alabama artist Tony Bingham were commissioned to create “Reunion Place,” which was showcased in the city’s historically Black Mechanicsville neighborhood.

At the time, Marie was teaching art at Georgia Southern University, and afterward she taught at the University of Georgia. But when the new millennium rolled around, she found herself back in the mountains, teaching at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, N.C..

Marie T. Cochran: I had gotten a job at Western Carolina University, and I was talking about how being there reminded me so much of my hometown of Toccoa. And I had a dear friend who is an educator. His name's Ernest Johnson, and he worked at the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching, right across the road from the campus. He was telling me about things that were happening — happening in Tennessee, that there was a group that was doing programing, generally around Black History Month, called "From Africa to Appalachia."

Chuck Reece: The late Sammie Nicely, a Black artist from the mountain town of Russellville, Tenn., was part of that group. Nicely was a contemporary folk artist, whose works were a mix of African, Appalachian, and Native American influences.

Marie T. Cochran: Long story short, I make a connection between this artist that has since passed on. A mentor for me, Sammie Nicely. And I would see Sammie Nicely at the Hammonds House in Atlanta, and we clicked it off because I could tell he had a twang to his voice.

Chuck Reece: In the following months, Marie met many other Black artists from the mountains. About the same time, she discovered the work of CeCe Conway. Professor Conway studied and taught folklore at Appalachian State University. In 1995, Conway published a book called African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia, which made it clear that what most people thought was a very white musical instrument, actually originated in Africa. All these new discoveries felt like fireworks in Marie Cochran’s head.

Marie T. Cochran: And it's like I'm hit. Like, these pings are happening. So then I go to an event called Wordfest in Asheville, and I meet Frank Walker. That's when I heard about the word. But before I heard about the word, I heard about all these things that were happening that were connected and aligned with this cultural phenomenon.

So Frank and I started talking a little bit, and then he came back another time and spoke at UNC Asheville. And then the real connection was when I went to dinner — we sat down at dinner and he said that they were having a gathering in Kentucky, the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and asked me if — because I was saying, well, you've got the music, you've got the poetry. Is anybody doing anything about visual art?

Chuck Reece: That was the beginning of the Affrilachia Artists Project. For almost 15 years now, Marie Cochran has gathered the work of African American visual artists in Appalachia. She has curated exhibitions of their work in museums up and down the eastern United States.

Her years of work raising the profiles of Affrilachian artists has led her to some important conclusions. One of those conclusions is this: The story of Appalachia isn’t a story of Black versus white; it’s a story about poor mountain people of all races who for centuries have seen their home region exploited for its riches — its timber, its coal and more. And then they’ve watched the companies that profited from those resources abandon the region.

Marie T. Cochran: This is also a story about class. It's about class.

Chuck Reece (from interview): It's a huge story about class.

Marie T. Cochran: In all of our American narratives, because of the way that Appalachia has been framed, it becomes a powerful case study for the nation. How it plays out, you know, where people who could work together have been pitted against each other. And I'm talking about everybody — Black, white, indigenous, immigrants. You know, the beautiful landscape being, you know, raped and pillaged.

It's a story of how people worked together and then how they got pitted against each other, to dismantle the community, the success that they had had.

Chuck Reece: Marie Cochran has been able to identify the connections among Appalachia’s people and the commonalities that rise above physical differences like skin color. And she was able to do that faster and better because she heard that magic word from Frank X. Walker.

Marie T. Cochran: Those poets were really — they were wanting to publish poetry. They were wanting to write. They wanted their writings collected. And what happened is the ripple effect of their work. Because it gave people a sense of agency. It made people who weren't Black start to think about how diverse their region was, and how they could start to reclaim the dignity and the possibility of the region. All these other people came on board. And as the brand of Affrilachia has been raised, it's more than a brand and it's more than a trend. It becomes a rallying point for all of these other conversations. It was breathing life into something that was, like, gasping for air and wanting more. It was a breath of fresh air.

Chuck Reece: When Marie taught me the magic word years ago, it felt like a breath of fresh air to me, too. The word Affrilachia told me that I could look at another mountain person whose skin happened to be darker than mine and still assume that the culture of the mountains connected us somehow.

Another poem from Frank X. Walker’s Affrilachia collection set the magic of the word so deeply into my heart that it could never be removed. It’s called “Amazin’ Grace.”

Frank X. Walker reading "Amazin' Grace":

Amazing grace! how sweet the sound / That saved a wretch like me! / I once was lost, but now am found

Was blind, but now I see . .

Chuck Reece: It’s a deeply familiar song. I would wager that for countless Southerners, it’s among the most familiar songs, its lyrics planted in our heads from childhood. Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary defines the word “grace” as, and I quote: “beneficence or generosity shown by God to humankind, divine favor unmerited by humankind.”

To put it in the plainest terms, grace is when you are forgiven, even when you don’t deserve to be. Like when your mama tells you she loves you and always will, even though you did something really stupid, like maybe dropping a lit match into the garbage can. And grace comes to all of us with no respect to race.

Frank X. Walker reading "Amazin' Grace":

It isn’t negro

but it is spiritual

it do speak to the power

of redemption

to power period

converting lost

to found

creating sight

where there was none

but what sound could be

so powerfully sweet

sweet enough

to turn a wretched

slave-ship captain

into england’s most outspoken

abolitionist and songwriter

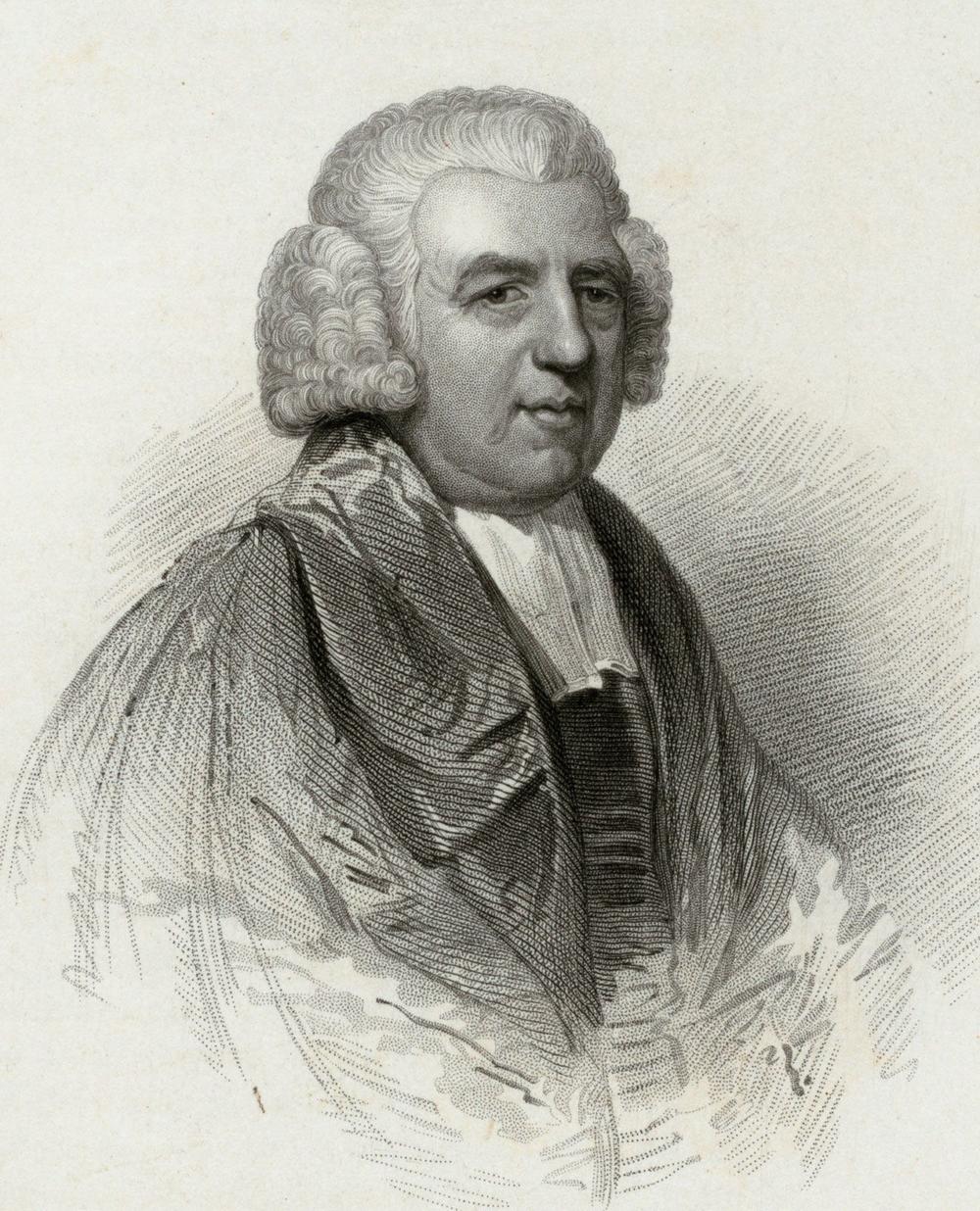

Chuck Reece: That slave ship captain’s name was John Newton. His ships brought kidnapped Africans by the hundreds in the West [of] Africa into the slave markets of the West Indies.

But after Newton left the sea in 1754 and returned to his home in Britain, he was plagued by guilt over his role in the slave trade. So he sought divine rescue. In 1764, he was ordained as a clergyman in the Church of England and began serving a parish in Olney, a village in Southeast England. Once there, he began writing hymns. And in 1772, he wrote “Amazing Grace.”

And he mentored William Wilberforce, who later led the fight to abolish the slave trade in Britain.

Frank X. Walker reading "Amazin' Grace":

was it the splash of bodies

dragged kicking and screaming

jettisoned off decks

to the outstretched arms

of ocean coral

was it the crack of the whip

or the popping sound bloody flesh makes

when a sizzling branding iron

breaks the skin

the sound of fear and confusion

below deck

muffled by the sound of rape up above

the sound of 609 beating hearts

sardined into a space for 300

amazing is to be lost and blind

and still the captain

a willing participant

in crimes against humanity

but what was that sound

that liberating release

granting pardons

for penitence undone?

what does forgiveness sound like?

Thro’ many dangers, toils and snares

I have already come…

now and every time you hear amazing grace

listen for john newton’s apology

his silent sobs seeking salvation

listen and hear

what healing sounds like

’Tis grace hath brought me safe thus far,

And grace will lead me home

Frank X. Walker: Even today, I think I'm always struck by how many people don't know the story. Who know the song, have lived the song their whole life. But when they hear the song after they've learned the story behind it, it … stops being the same song. Or they stop being the same person. … It’s one of those two.

Chuck Reece: For me, it was both. And that was long ago, when I first learned the story of John Newton’s redemption.

Chuck Reece (from interview): But through stories like that, white people and Black people who grew up in Appalachia can find understanding with each other that runs at a deeper level than they think they were allowed to go.

Frank X. Walker: You know, I think of it as kind of a, a special vibration that happens for people when they realize that, you know, they have a shared humanity with somebody else. And it usually happens through trauma or, or some painful event or through a religious experience. You know, at some point, you know, you know, you look up and somebody else is also hurting or full of joy, and they're witnessing the same thing that you're witnessing. And in that moment, you recognize that there isn't that much distance between the two of you because you’re both feeling the same thing.

OUTRO

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank Frank X. Walker for all the time he spent with us here in the studios of Georgia Public Broadcasting. He is the author of twelve collections of poetry. The latest is called Load in Nine Times, and it’s remarkable. More than 80 poems, all of which are based on Frank’s extensive research into the lives of members of the U.S. Colored Troops, who fought alongside the U.S. Army to defeat the Confederacy in the Civil War: including two of Frank’s own ancestors: Randal Edelen of the 125th U.S. Colored Infantry and Henry Clay Walker of the 12th U.S. Colored Troops Heavy Artillery. And we’re actually going to ask Frank back for a future episode about that stories — another piece of Southern history most of us did not learn in school.

Thanks also to Marie T. Cochran, founder of the Affrilachian Artists Project. Marie is just beginning a fascinating, yearlong project with Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies. In that project, she wants to bring together a diverse mix of people to curate a visual-art exhibition focusing on issues of race in Appalachia. We’re hoping, when that work is complete, to bring you that story, too.

If you’d like to participate in Marie's project, you can send an email to docstudies@duke.edu.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of 20 stations around our state. Every Wednesday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, an online magazine that you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com. Our producer is the Jake Cook. Jake also wrote and performed our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell. And we have to say that this show happens thanks to the amazing grace of some wonderful people here at GPB — GPB’s Sandy Malcolm, Adam Woodlief, and Bert Wesley Huffman.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

꧁🙟⎯✣⎯⎯⎯⚜⎯⎯⎯✣⎯🙜꧂

To learn more, visit these links:

Affrilachian Artist Project

Frank X. Walker Website

Salvation South interview with Frank X. Walker

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.