Section Branding

Header Content

The Girls Of The Leesburg Stockade

Primary Content

Many of the struggles of the Civil Rights era are well known. Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat, the March on Washington, Bloody Sunday in Selma, and the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Others remain hidden, or only known to a few. In 1963, more than a dozen African American girls, aged 13-15, were held in a stockade for two months. Their crime: demonstrating for integration in Americus, Georgia.

It’s an unremarkable cinder block building, just outside Leesburg. The inside is drab and windowless. Concrete floors, fluorescent lights, bare walls. The city used it as office space, and it once housed the county’s 911 call center.

Carol Barner-Seay remembers every detail of how it looked in 1963. She’s returned many times over the years. “I’m just grateful to keep coming back to see where I was,” she said. “Even though it held me then, it don’t hold me now. So, when I left I didn’t take this with me.”

For Emmarene Streeter, it’s her first time back in over 50 years. When asked what’s it like to be back, she sighs, holds up her hand, and walks into another room.

These women, and thirteen others, spent 45 days in this building for challenging the ways of the segregated South.

Starting in 1962, Americus, Albany, and other towns in Southwest Georgia were the focus of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The group first came to the region to register black voters, but their focus shifted to direct action. Massive protests to integrate bus stations, movie theaters, and other public spaces. Hundreds turned up to SNCC organizing meetings. Many were teenagers...or younger, like Diane Dorsey-Bowens. She was 13 at the time. Her grandmother would send her to the drug store.

“When you walk in...’There’s a pickaninny!’ ‘Here comes another pickaninny!’ All kinds, saying everything to you, making me feel so bad,” she said. “So, when the movement came to Americus, Georgia, I was just fired up. I was just ready to go, ready to join. To try to change, to do something.”

Carol Barner-Seay also attended the meetings. She took part in a few marches, but would always back out at the last minute.

“So one day I finally made up my mind. Today's the day. Carol, today is the day,” she said. “You will stay in line. You won't get out. And no matter what happen, If I don't make it by to see my mom, my dad, my sisters and brothers, it would be OK. Maybe just maybe my siblings won't have to go to the hell that I'm going through.”

It was the day in July of 1963 that SNCC protested a segregated movie theater. “We did not move. but I had at that time no no no idea that we was going to be going and going to jail,” said Shirley Reese. She was 14 at the time, waiting in line at the theater to buy a ticket. After about 30 minutes, a big truck pulled up. Police officers said everyone in line was under arrest. “And you can imagine what I was thinking about then. I had snuck away from home. My mama didn't know where I was because they was not home. And here I am being arrested.”

The protesters were taken to Dawson, about 30 miles south of Americus, where they spent the night in jail. The next day, they were hauled to the stockade in Lee County.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WCr9XuaE9SQ&feature=youtu.be

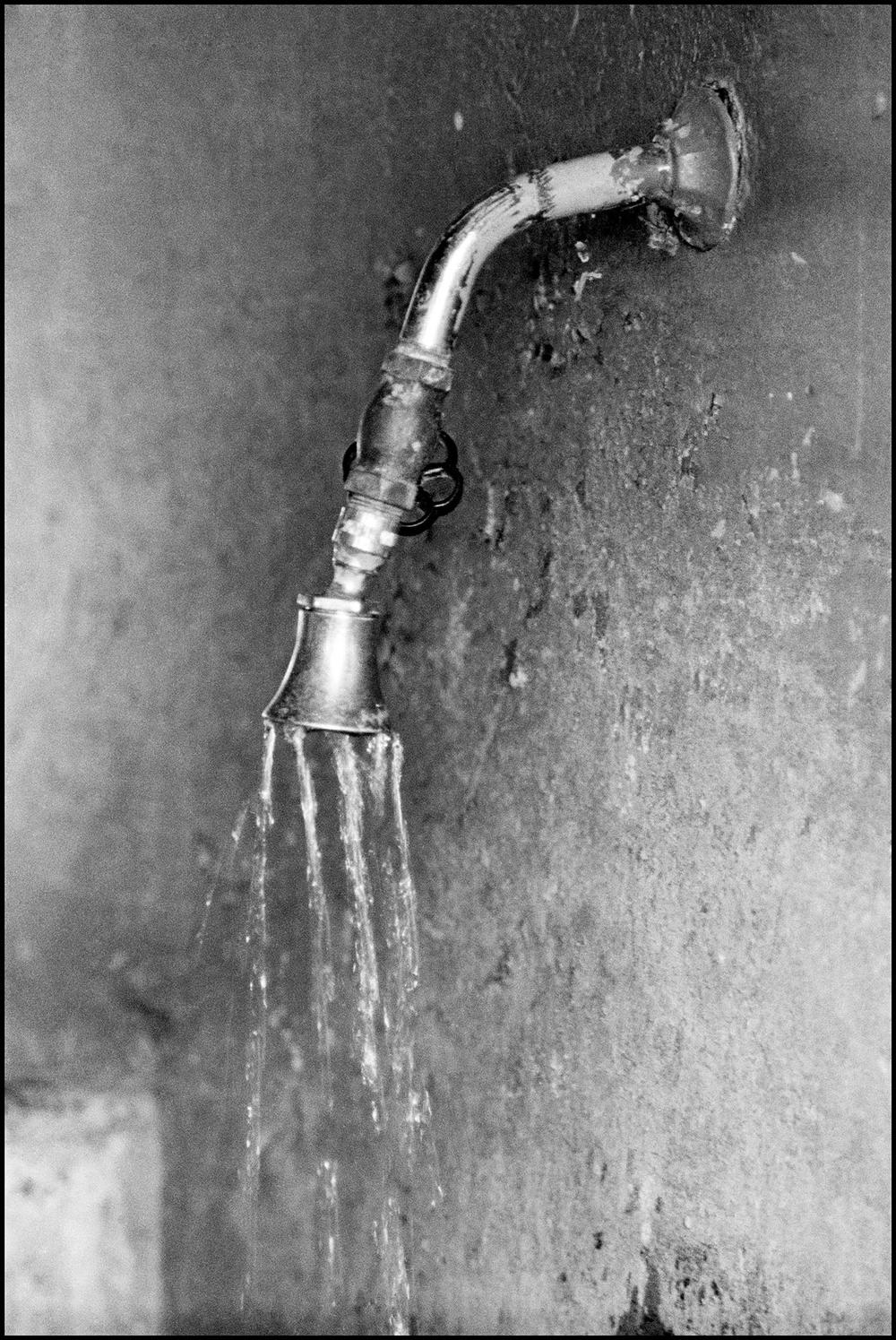

Carol Barner-Seay said for weeks they slept on cement floors, used a common toilet that quickly stopped up, and ate nothing but egg sandwiches and undercooked hamburgers. The only water came from a dripping shower head.

“Can you imagine that you were in there with girls and you were in the this long with no bath, no toothbrush, toothpaste to brush your teeth?” she said.

The girls’ families had no idea where they were. The local dogcatcher, who brought food, eventually told their parents.

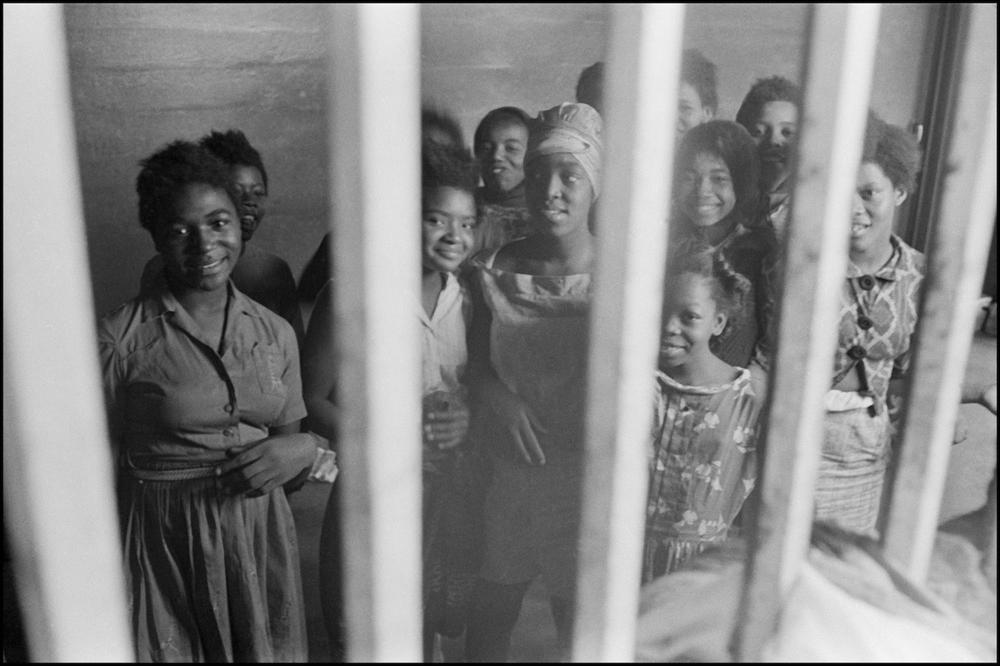

Word eventually got back to SNCC. A 21-year-old volunteer, Danny Lyon, traveled to Leesburg, snuck into the stockade, and shot about 20 photographs.

Lyon’s pictures were published in a SNCC newsletter, and later in Jet magazine and other black-owned publications.The Chicago Defender ran the images under the headline, “Kids Sleeping on Jail Floor: Americus Hellhole for Many”

The girls were finally released in mid-September, 1963. They were never charged with any crime, but their parents each had to pay a two dollar boarding fee.

It was a Friday, and they were expected at school the following Monday. Carol Barner-Seay says none of their classmates asked what happened to them.

“The only thing I heard while we were changing classes there was a group of kids that would just be standing there just staring at you,” she said. “And then all of a sudden you'd hear this: ‘What kind of bird don't fly?’ and then somebody said, ‘A jail bird!’ And then they all run away. One of the girls got agitated about that. And I went to her and I said don't let it bother you because they don't understand. I said what we did we did it not for us but for everybody.”

Emmarene Streeter didn’t talk about her experience for years. And that silence shaped her life. She says she wished she and the other girls received counselling after they left the stockade.

“I went on become a guidance counselor myself,” she said. “To help the children also, but to help me.”

Nine of the fifteen women are still living. Some moved far away from Americus. Shirley Reese returned a few years ago, and now serves on the city council.

Earlier this year, the General Assembly passed a resolution honoring the women. Georgia congressmen John Lewis, Sanford Bishop, and Hank Johnson have nominated them for the Presidential Medal of Freedom.