Section Branding

Header Content

School Choice Presents Challenges In Rural Georgia

Primary Content

This year could be a big one for school choice. State lawmakers are considering expanding a program that gives tax credits to Georgians who help bankroll private school scholarships.

Supporters say the program gives students in public schools better access to other education options. But for many Georgians, especially those living in rural communities, those options are hard to find.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, the Central High School gym in Talbotton, Georgia was filled almost to capacity, a sea of proud blue and gold.

The boys basketball team was in the playoffs, and the hometown crowd watched with rapt attention as the Central Hawks faced the Irwin County Indians, another team from one of Georgia’s many rural counties.

The event was a big deal, a chance for the community to come together.

“In small cities like these, basketball games tend to be a gathering: basketball games and churches,” said Cynthia Epps, Assistant Superintendent for Talbot County Schools and a graduate of Central.

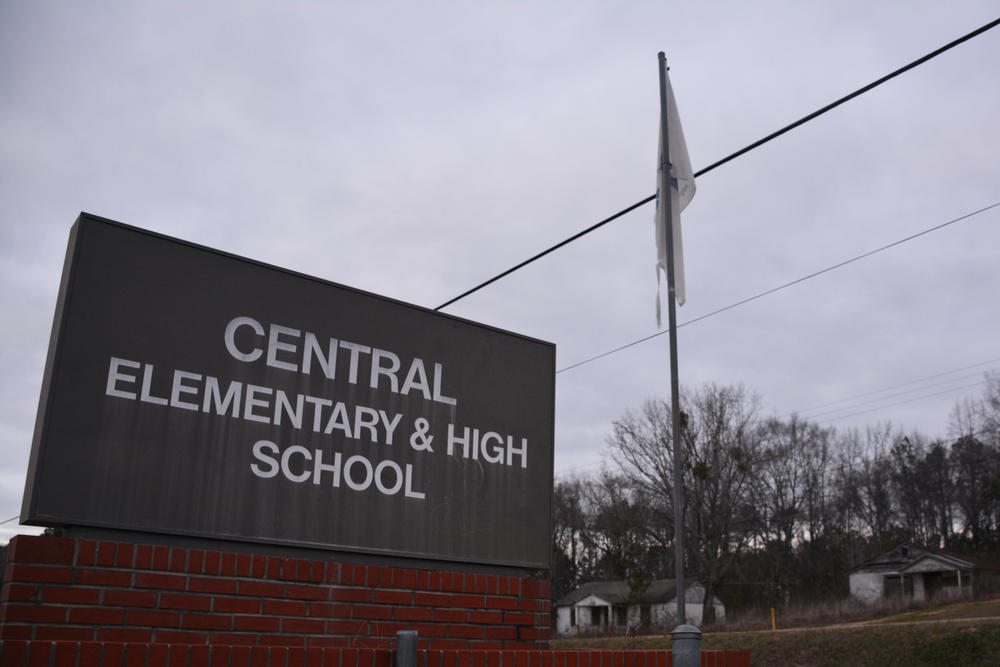

The public system of under 500 students, most of them African-American, has just one elementary, middle, and high school on one campus just north of Talbotton, a city of just a few traffic lights.

Across the street from the campus sits a row of abandoned homes, a sign of the community’s economic decline. There aren’t many jobs here, and one-in-four Talbot County residents live below the poverty line.

Talbot County Schools don’t perform particularly well. In 2016, the system had one of the lowest scores on Georgia's College and Career Ready Performance Index.

On top of that, they offer a limited curriculum. There are no art classes, no languages other than Spanish, and students looking to take Advanced Placement courses have to do so online.

But Talbot County Schools are the only schools here. Students looking for other options have to travel to neighboring counties, and that’s not always easy.

“This school is very paramount to this community. I’m a native of this county, and I’ll tell anyone, ‘Yes, I believe in this school. It’s going to get better,’” Epps said.

Still, she knows not everyone has her faith. Epps said parents take their kids out of the district, and more would do so if they had the means.

“If you dangle that opportunity in front of our parents, yes, they may want to do it,” Epps said. “Probably about five, ten percent of our families could transport their kids out, but what about the other 80 percent? Other 75 percent?”

“I can grant that that’s not practical for everyone,” said Rep. Sam Teasley (R - Marietta).

He’s sponsoring a pair of bills this session he hopes will make non-public education options more attractive and attainable to parents.

The legislation would expand the cap on a program that gives Georgians tax credits for bankrolling Student Scholarship Organizations (SSOs), which hand out private school scholarships to eligible students.

The program has been wildly popular. In recent years, it's reached its $58 million dollar cap on the first day and has subsidized private education for thousands of students.

“It is certainly my hope that where there are needs for students to be met, these parents are afforded more opportunities more choices so that their children can be in a school that fits their family’s needs,” Teasley said.

Teasley argued more school choice is good for all Georgians, even those who live in one of the state’s 48 counties without any private schools.

But it’s hard to pin down exactly what impact the program has had since it launched in 2008.

“We know very little about how it’s worked,” said Claire Suggs, an education policy analyst with the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

She said there’s little information on the program, because the state doesn’t collect much data about it. There’s no master list of participating schools and no information the financial need of the students who receive scholarships.

What little data there is comes from the Georgia Department of Revenue. GPB News contacted DOR seeking information about the origins of donations to SSOs and about scholarship recipients, but the department said it didn’t have it.

We sought similar information from the Georgia GOAL Scholarship Program, the largest of Georgia’s SSOs. But Georgia GOAL denied our request, arguing they dealt only with private funds, not taxpayer dollars. Whether or not that’s the case is a question currently under consideration by the state Supreme Court.

“Well, certainly we know what the fiscal effect is,” said Claire Suggs. “Those are dollars that are diverted away from the state’s general fund and that would otherwise be used to fund other critical needs for the state."

And though there’s no guarantee the money given out as tax credits would have funded schools, education tends to take up the largest part of Georgia's budget.

“Choice sounds like a wonderful thing except when it unfairly disadvantages a particular group or set of people,” said Doris Williams, who studies education for the Rural School and Community Trust.

She said expanding school choice can come at the cost of harming small, rural school districts, especially in places like Georgia where state education funding is tied to enrollment.

“If you take out kids from those schools and the funding that goes with them, you’re in effect killing those schools,” Williams said.

That, plus the fact that these districts tend not to have many options in the first place, makes school choice seem more like a threat to rural communities than an opportunity.

Back at the Central High School gym, as she watched the boys basketball game wind down, Talbot County Assistant Superintendent Cynthia Epps said she doesn’t blame parents for wanting the best options for their kids.

“But in our case, most of us [are] gonna have to stay put,” Epps said. “We’re gonna have to stay on this boat--this educational boat, and we’re going to have to ride it through, and we’re going to have to graduate kids who are ready to move to the next level.”

She said her job is to convince families to believe in Talbot County Schools as much as she does. She wants them to see their local public high school as a good school choice.

Note: Grant Blankenship contributed to this report.