Section Branding

Header Content

Two Sides, One Confederate Flag, And No Clear Resolution In Henry County

Primary Content

The Civil War ended 152 years ago, but some of its battles are still being fought in Henry County, Georgia.

On the grounds of Nash Farm Battlefield, there’s an outdoor wedding chapel, markers commemorating the Battle of Lovejoy and, until recently, a Civil War museum.

The volunteers who ran Nash Farm Battlefield Museum closed its doors after they say a County Commissioner forced them to remove the flags from display.

The commissioner says it’s not about the flag, but making her constituents feel safe. Others see it differently.

'A GENTLEMAN'S AGREEMENT'

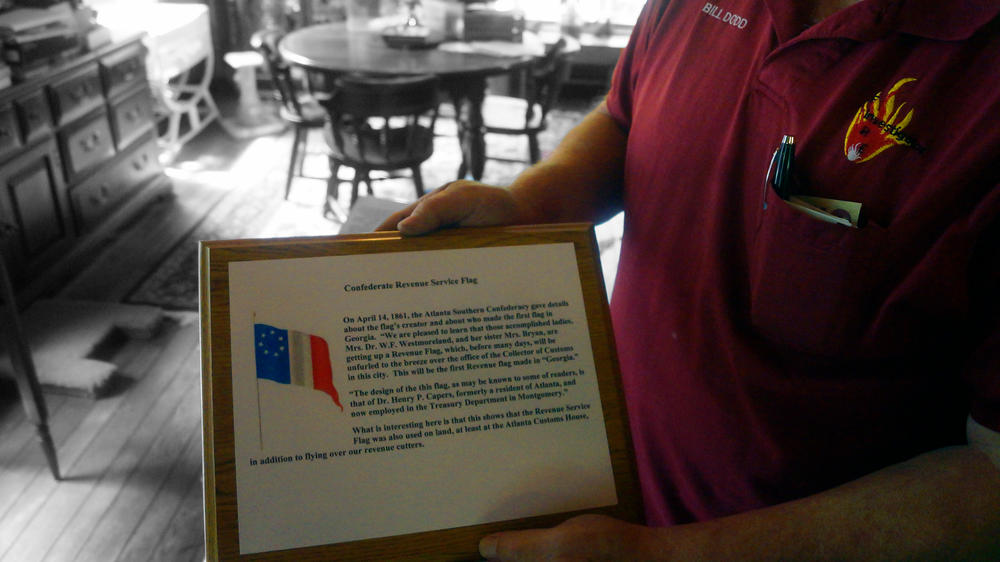

To say Bill Dodd is stuck in the past isn't an insult, it's just his way of life.

Dodd is a collector.

His home is a historian's heaven, filled to the brim with knickknacks and bibelots, ranging from Civil War bullets to modern British Bobby helmets.

"What got me started collecting Civil War memorabilia, is I grew up on a battlefield," Dodd said. "As a small child, when my daddy would plow the garden, I would pick up the Minié balls out of the garden."

He was the curator of Nash Farm Battlefield museum, and was responsible for a considerable amount of the memorabilia on display.

But what Bill Dodd wants you to know is that the only person responsible for closing Nash Farm Battlefield Museum was him.

"I agreed to set up the museum if I was the curator," Dodd said. "And as curator, I would have final say over what would be displayed, how it would be displayed, how it would be portrayed and where it would be located at in the museum."

Dodd says three of those rules were broken, so he was out.

The museum operated under a gentleman's agreement. For close to 10 years, there was no "official" arrangement for volunteers to operate on county property, but there wasn't opposition, either.

That changed after the election of Henry County Commissioner Dee Clemmons, the first African-American woman to hold that role.

In an interview on talk radio station WAOK-AM, Clemmons said a number of her constituents expressed concern about Confederate flags flying on county property.

"The people of Henry County elected me to be good stewards of the county property," Clemmons said. "So, with that being said it is my responsibility to ask questions."

According to Clemmons, those questions led her to request that a Confederate flag be removed from a flagpole and other flags be moved away from windows.

The museum's volunteer board says Clemmons asked for the flags to be completely gone – so they packed up and locked the doors.

What would have been a mundane squabble in local governance has instead ignited a firestorm of debate about history, hate and the Confederate flag.

'WE ARE OFTEN MISUNDERSTOOD'

On one side of the debate is Wes Freeman, a 68-year-old Vietnam War veteran.

He and about 250 other Confederate flag supporters showed up at Nash Farm on a recent Saturday morning to defend what they see as a sustained attack on the intelligence, culture, and history of those in the South.

"They think we're a bunch of redneck, knucklehead, tobacco-spittin'-chewin'-womanizin'… boozers," Freeman railed. "OK, I like my chewing tobacco, I like my cigars, and I like my beer. But I’m not a redneck dumbass."

Flags of all sizes flapped in the wind as dozens of Henry County residents took turns airing grievances at the international attention that's been laser-focused on this community.

Another speaker was Chris Hill. He leads a local militia, the Georgia Security Force III%, and is no stranger to having to defend himself.

The Southern Poverty Law Center labels the III%ers an anti-government hate group known for anti-Islamic views.

But Hill says the Confederate flag has been co-opted by real hate groups, and feels removing the flag maligns and misrepresents Southerners – and groups like the III%ers.

"I look at it as an assault on our way of life, I look at it as an assault on history," Hill said at the rally. "We are often misunderstood as being affiliated with racist groups, and the media does a good job of lumping us all together."

For some people, the flag is one of the few remaining links to their Southern ancestry.

'DO NOT ERASE ITS PRESENCE'

Accompanied by a cacophony of jackhammers and drills and the pouring rain, Gordon Jones is working to preserve all aspects of ancestry in the South.

Jones is the senior military historian and curator at the Atlanta History Center.

He's standing in the construction zone of a new building that will house the famous 1886 Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama painting.

Surrounded by 15,000 square feet of warring Union and Confederate soldiers, Jones said historical artifacts are awash with stories that need to be told – even things that paint us in a negative light.

"History can be, and often times is, unpleasant," Jones remarked. "Nevertheless, those types of things still deserve our attention today, lest we make the same mistakes in our present time."

According to Jones, the importance of meaningful curation is documentation of an artifact's significance as well as the greater context of the time it existed in.

As far as what he thinks about Confederate monuments being removed around the country? It's a local thing.

"This is grassroots democracy in action," Jones said. "What's right for your community in your particular situation is not necessarily gonna be right for this community and that particular situation."

As a historian, though, Jones said if things are removed, the historical meaning and documentation needs to be preserved.

"Make sure that we do not simply erase its presence from the historical record," he cautioned. "And make sure whatever decisions we make are made with all due consideration for that history, and are made intentionally."

‘IT’S DRIVEN A DEEPER WEDGE’

On the other side of the debate, and on the other side of town, dozens of community members wish the flag’s ancestral link would go away.

At a recent County Commission meeting, more than 300 people sat through a slog of zoning updates, tweaked ordinances and a proclamation of Caribbean American Heritage Month to make their voices heard.

55 people from near and far spoke their mind at the four-hour meeting.

They voiced support for Nash Farm, for Commissioner Clemmons, for African-American survival and for history. Each speaker was determined to prove that in the flag fight, their side would be the winner.

Sarah Billups is the Community Coordinator for the Henry County NAACP.

She held up an American flag as she spoke in support of Commissioner Clemmons.

“This is the flag that we all should be flying,” Billups said, the passion rising in her voice. “This is the flag that my brothers went and served in the armed forces under. The Confederate flag has been dead for 150 years plus.”

One thing that won’t die anytime soon is the tension that has been wrested to the surface in this quiet suburban community.

As McDonough resident Don Henderson pointed out during his five-minute allotment, everyone in this tale is the loser.

“Miss Clemmons is on social media saying she wanted to unite this county,” Henderson said. “I can tell you what she has done did not unite this county… it’s driven a wedge deeper than it ever was.”

But some things will change.

The county manager announced a review of standards and policies for parks, and the Commission chair has asked for a master plan for the battlefield to be discussed by all the commissioners.

For now, there are no plans to reopen the museum, and just like the collections in Bill Dodd’s house, the story of the Confederate flag at Nash Farm will soon become history itself.