Section Branding

Header Content

Lawyers Ask Panel To Spare Life Of Inmate Set For Execution

Primary Content

A Georgia prisoner scheduled for execution this week has spent the last 27 years regretting the decisions that led him to kill his sister-in-law as she was on her way to work with his estranged wife, his lawyers said in a clemency application.

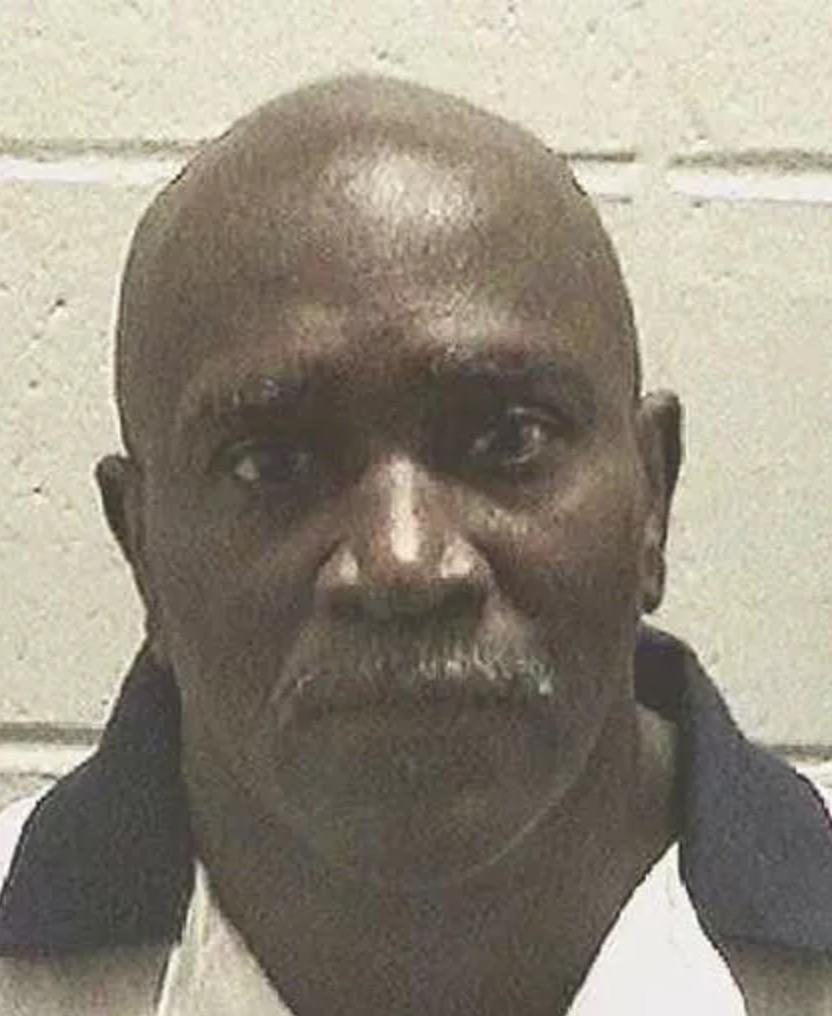

Keith Leroy Tharpe, 59, is scheduled to be put to death Tuesday at the state prison in Jackson for the September 1990 shooting death of Jacquelyn Freeman.

The State Board of Pardons and Paroles was holding a hearing Monday — the 27th anniversary of Freeman's death — on Tharpe's clemency petition. The parole board is the only authority in Georgia that can commute a death sentence.

In a clemency application that was declassified Friday, Tharpe's lawyers detail a tough childhood and an extensive history of substance abuse that they say included getting black-out drunk by age 10 and a debilitating crack cocaine habit.

Tharpe's wife left him Aug. 28, 1990, taking their four daughters with her to live with her mother.

His addiction coupled with intellectual disabilities dating to childhood left him unable to deal effectively with the stress of losing his family, his lawyers wrote in the clemency application.

He drank and smoked crack until early on Sept. 25, 1990, his lawyers wrote. As his wife was driving to work with her brother's wife that morning, he used a borrowed truck to block them. He got out armed with a shotgun and ended up killing Freeman.

Tharpe went to trial in Jones County a little more than three months after the killing and was convicted and sentenced to death.

In the clemency application, his lawyers describe a changed man who has kicked his addictions, devoted his life to God and sought to help improve the lives of others while also developing deep remorse.

"He wishes more than anything he could take back that day and give back Mrs. Freeman's life," Tharpe's lawyers wrote.

The clemency application includes testimonials from Tharpe's mother, one of his daughters, other family members, prison staff, clergy members and friends.

His lawyers also ask the parole board to consider their assertion that his death sentence is tainted by the racial bias of a juror who freely used a racial slur in conversations with Tharpe's legal team more than seven years after the trial.

Barney Gattie, who has since died, said Freeman came from a family of "nice black folks" and Tharpe "wasn't in the 'good' black folks category in my book" and so should be executed for what he did, according to an affidavit he signed in May 1998.

"After studying the Bible, I have wondered if black people even have souls," Gattie said in the affidavit.

State lawyers met with Gattie two days after he signed that affidavit and he walked back much of what he'd said, ultimately saying race wasn't an issue during jury deliberations and that he voted for a death sentence because of the evidence against Tharpe, not because of his race.

A federal judge earlier this month declined to reopen Tharpe's case, and a three-judge panel of the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on Thursday rejected his appeal. But the panel said that in light of U.S. Supreme Court decision earlier this year on racial prejudice in jury deliberations, Tharpe must make those arguments in state court first.

Tharpe's lawyers are appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court and are also pursuing action in state court.

If executed, Tharpe would be the second inmate put to death in Georgia this year.

Bottom Content