Section Branding

Header Content

Spirituality And Reclamation Shown In Atlanta Artist's "Do or Die" Exhibit

Primary Content

Images are powerful. It was cell phone video and stills of unarmed black men and women being killed over the past several years that launched inquiries into use of force by police and sparked the Black Lives Matter movement. It's what inspired visual and performance artist and scholar Fahamu Pecou for his new exhibit showing at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University.

On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott speaks with Fahamu Pecou

Pecou began working on his "DO or DIE: Affect, Ritual, Resistance" project in 2015 with a couple of questions in mind: How does one heal after tragedy? And can one gather strength from the stories and spirits of those who've lost their lives?

Pecou spoke with On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott about his journey in finding answers for those questions. It included spritual practices in the West African Yoruba tradition called Ifa.

Pecou's art exhibition is on display through April 28.

Interview highlights

On what guided/inspired this thesis

So, the large question that drives its body of work is what kind of life could you live if you weren't afraid to die? What was really interesting to me was this idea that the visual culture and visual narratives around black existence in this country are so intertwined and interwoven with spectacles of death, that death sort of underscores black life in ways that prevent black people from living full, thriving lives. I wanted to create a body of work that would be in conversation with this spectacle.

On taking back the power of trauma

That would not re affirm it. That would not endorse it. That would not play into the traumas that the visual narratives have created but would instead resist the idea that this threat of death and threat of violence that has been so pervasive over black lives for centuries that it didn't have any weight. I wanted to take the sting of that threat away.

On black death and black life

I should also note too that when I referred to the spectacle of black death. I'm not just referring to the physical death or destruction of the body but also the kind of social death that is also inspired in these images. I wanted to create something that would affirm our lives that would give us a healthy way to think about our existence, our presence, our possibility.

On how representations of black tragedy shaped his own life

“What kind of life could you live if you weren't afraid to die?” has been a question that has animated my own existence in the world. I spent so much of my young adult life from about the ages of 18 to 28 anticipating my own demise to the extent that I didn't really even acknowledge or celebrate accomplishments that I had. I was more so ticking off the tragedies that I avoided, because I have been fed this healthy diet of negative ideas and stereotypes and images about my existence as a black man for so long that ultimately I just assumed, “What's the point in it all?”

On how Menace ll Society impacted him

The statistics are daunting. I recently did a TED talk and I shared this experience that I had when I was 18 and I saw the film Menace ll Society. Literally after walking out of the theater that day I was just waiting on a drive by or some crazy thing to happen to me. Mind you, I was about as far removed from that kind of lifestyle as anyone could be, but just being a black man and seeing those kinds of images, hearing those kinds of stories over and over again, I just assumed that that was going to happen to me.

On how the spiritual Ifa tradition changed his life

Art was a way for me to work through some of this trauma, and thinking about the fact that my art was was really rooted in this spiritual ideology that I didn't quite have a language for until I was introduced to Ifá around 2002. It piqued my interest ended up going to a Temple here in Atlanta, and it was the first time that I ever walked into a religious or spiritual institution or space and felt instantly at home.

On the concept of re-memory

I've been exploring this concept that's very popular amongst African philosophers called re-memory. Essentially, [it is] this concept rooted in the idea that black subjectivity has been fragmented, destroyed, dismembered, and disfigured, and that the one true way to really understand one's subjectivity is to remember those pieces; to put yourself back together [so you can] understand your cultural memory, language, history, and spirituality.

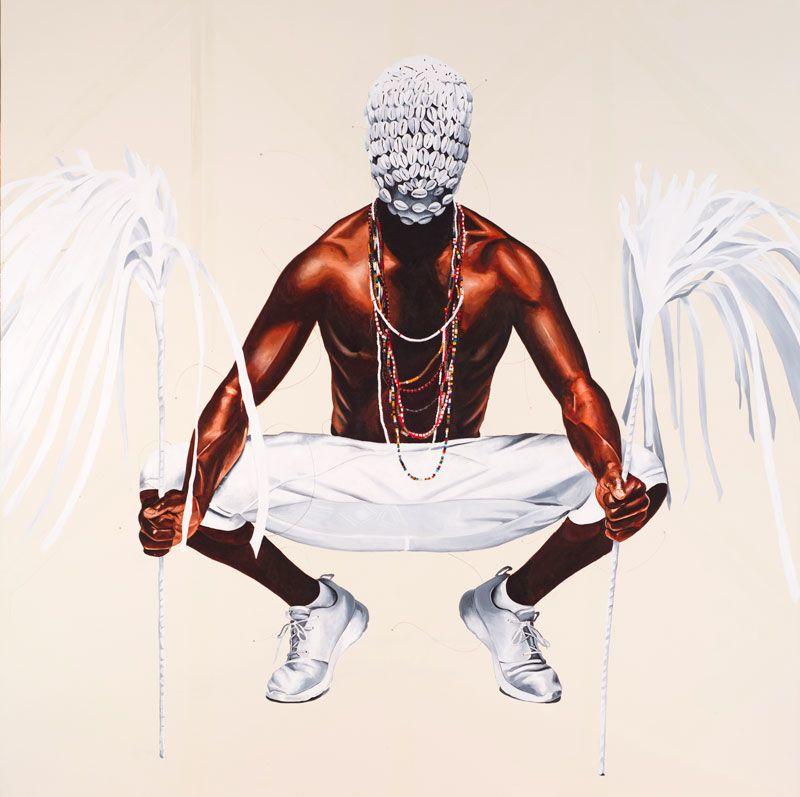

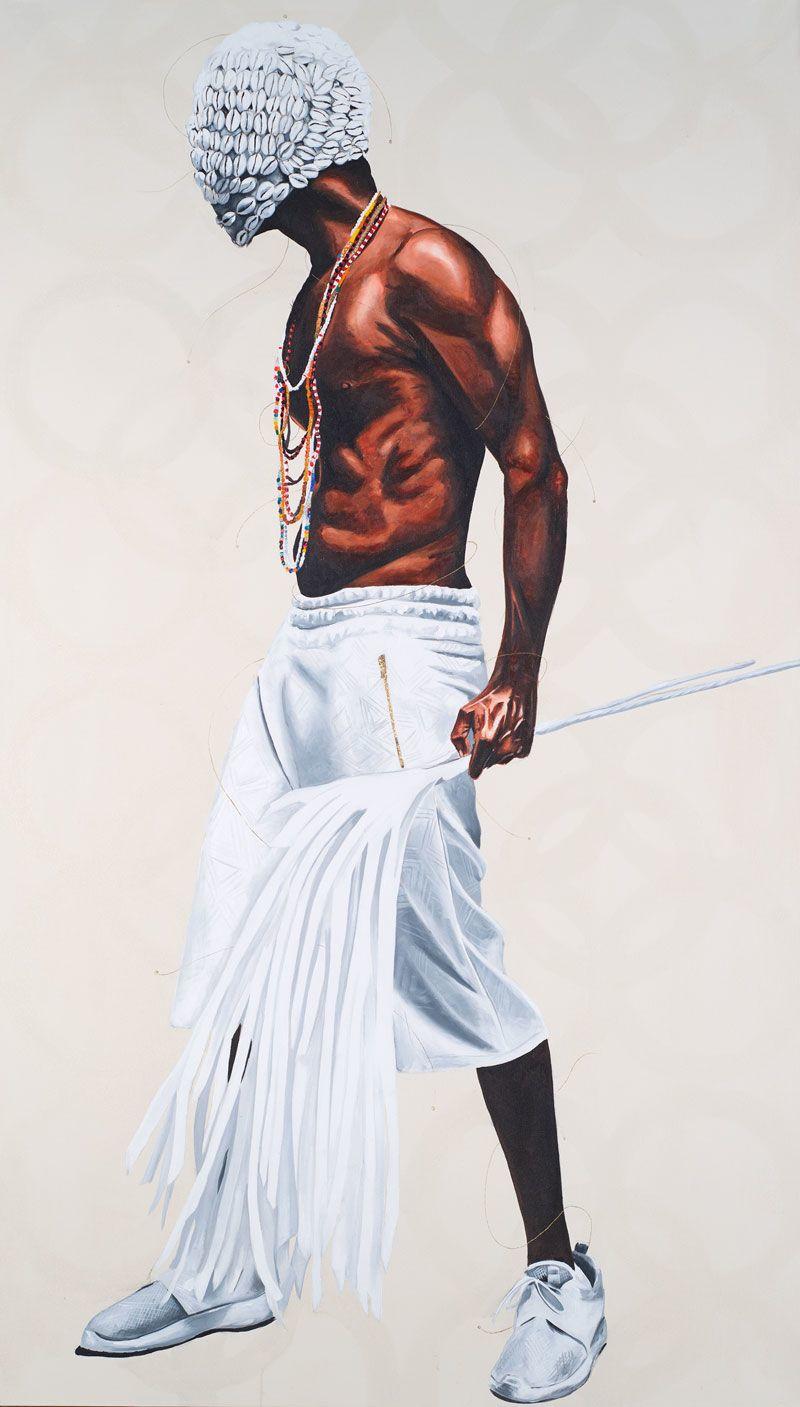

On the significance of his “New Word Egungun” piece

So egungun in the Yoruba tradition are the ancestors, so an egungun mask gives shape and form to these unseen and ancestral spirits. My “New World Egungun” [piece] is an egungun that I created specifically to honor the lives of black men and boys who have been killed by various racist forms of violence. It just largely [represents] the disruption of violence to black bodies in this new world context.

On the meaning behind the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church site

To give the full picture, the Egungun actually emerges from the waterfront in downtown Charleston, which was also the site where hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans disembarked in the New World. So the egungun starts at that point and moves through downtown Charleston along King Street, and stops at the AME Church to collect, honor, and elevate the spirits of those nine parishioners who were tragically killed. This performance is called an elevation ritual, and it is designed to do exactly that.

On how he retains hope in the face of tragedy and violence

For me, the idea that beyond the physical our spirits are eternal and [can even] return is a really powerful visual. It's a really powerful awareness, especially in the face of this impending doom of violence that continues to be imposed upon our bodies. From the very beginning of the histories of enslaved African people, violence and death has been used as a means to control and coerce you into doing what others have demanded of you. I think has led to a deep perversion of the idea of death. I wanted to create a body of work that would say you can't destroy us. I think that there's hope in that. This body ends, but another body will begin.

On the role ancestors play in the Ifa tradition

I really love the way that ancestors are considered in the Ifa tradition. You can talk to them anytime; they are allies in the spirit world, your first line [of defense]. It was described to me as [similar to] when you were a little boy and you skinned your knee, you would run to grandma and she would kiss your booboo. Our ancestors are are the same thing; when we run into an issue or challenge in our lives, we can go to Grandma in the spiritual realm and ask her for her assistance. It’s [this] cyclical, symbiotic relationship and it's just a really beautiful concept.

On the Ifa tradition version of karma

You do no harm because you inherit what you are leaving. So why destroy the planet that you live on, why create a negative environment to have to come back to? You want to do good. Iwa Pele [means] to “live with good character” and I just think that that is beyond hopeful. That is an aspiration.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=cFpAXYIBXEE

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457