Section Branding

Header Content

'Monumental Lies' Wins Peabody For Investigation Into Government Spending On Confederate Memorials

Primary Content

The Peabody Awards announced winners in radio and podcasting this week, among them Type Investigations and Reveal for their "Monumental Lies" episode. After filing 175 open records requests to track public spending on Confederate memorials and organizations, reporters Brian Palmer and Seth Freed Wessler found that more than $40 million in state and federal funds have been spent on the maintenance and expansion of such monuments and sites over the past decade.

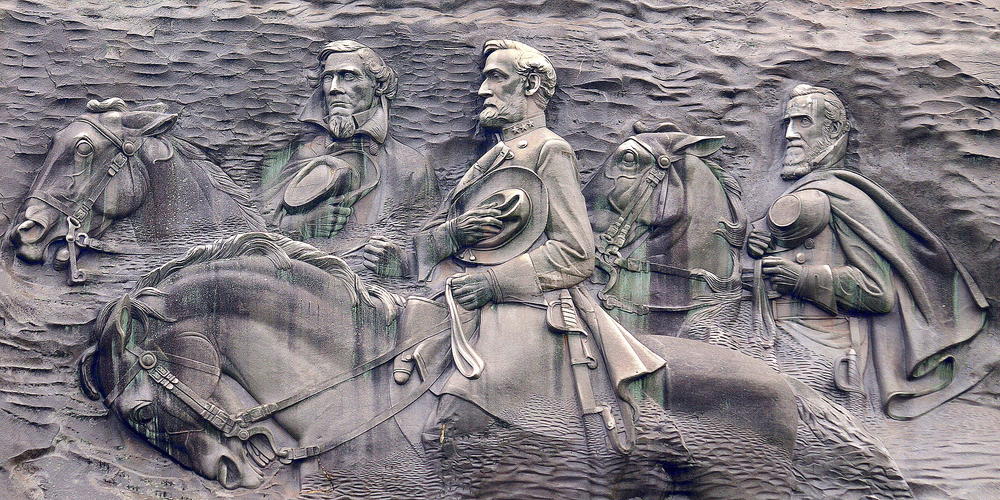

The pair also visited more than 50 of those sites, including the A. H. Stephens State Park in Crawfordville, the Robert Toombs House Historic Site in Wilkes County and Stone Mountain in metro Atlanta. They found some of them omit, or revise, the namesakes' history with slavery. We spoke with Palmer and Freed Wessler last year when their investigation, which they also published in Smithsonian Magazine, came out.

On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott speaks with Brian Palmer and Seth Freed Wessler.

On how they started the investigation

We went on the road and began visiting dozens of places that tell the story of the Civil War, the Confederacy, and slavery to really try to figure out what the story was that was being told at these sites. At the same time, we tried to figure out how much money was being spent on these sites so we filed dozens of public records requests and called through tax documents, public records, and public legislative reports to figure out what we're spending on on these places.

On what they discovered:

What we found is that many Confederate sites are telling a story that's not based in fact, but grounded in narratives that defend the Confederacy and paint a picture of the history of slavery that whitewashes history entirely.

On the money spent to upkeep these monuments

$40 million [spent] in the past 10 years [is a] significant amount of money but my real concern, in addition to how much is being spent, is how much went in to subsidizing these sites that present a narrative that either distorts or erases the enslavement of African Americans, my ancestors.

On the origin and duration of the money spent

The first push of monument construction was really the 1880s to the 1890s. That is where you see public funding as well as significant private donations going into the funding of these places. But Confederate Memorial associations were receiving money to take care of cemeteries directly after the Civil War. You had a lot of Confederate deceased soldiers that needed to be buried, [but] that money which started to flow in 1860 just kept flowing. So there are all of these really creative ways to keep these subsidies, not simply for the initial purpose.

On what that money is being used for now

In Georgia there are a number of state and county run parks where there is a full articulation of the Civil War’s history and leaders, [and] public money is supporting these sites to keep them running. In many cases, the public money is just going to keep them operating as they have for decades. In some cases these places have expanded.

On institutions that have expanded

We spent a lot of time writing about Beauvoir, the Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library located in Biloxi, Mississippi. That institution has received over $20 million in the last decade, money which came from the federal government and the state of Mississippi that has helped the place expand. After Hurricane Katrina the estate was heavily damaged, and federal dollars went to Beauvoir to help it rebuild. Half of the $17 million that came from the federal government went to build a new museum and library that didn't exist before the storm. [Both of these places] tell a story about Jefferson Davis and the Civil War that glorify him, talk about the bravery of Confederate soldiers, and propose that Jefferson Davis was a benevolent slave owner.

On Confederate institutions in Georgia

We found a very similar narrative at the Robert Toombs house in Washington, Georgia. [It] doesn't get the same amount of funding, but it had a lovely renovation; again, substantially with public funding. When I visited I was the only person there, and I went through the entire house and saw the periodization of Mr. Tombs' career, but nothing on the walls about slavery and his role in enslaving people. So I asked a docent where that was, and she said [that] they didn’t have anything on the wall, but she handed me a WPA Slave Narrative by Alonza Fantroy Toombs. This gentleman was singing the praises of his Massa and his enslavement. We are used to having people deploy the so-called black Confederate and the loyal slave.

On the erasure of slavery

At both the Robert Toombs House and the A.H. Stephens State Park (both of which are in Georgia and owned by the state or county) we hear this story about valiant and noble Confederate leaders but no narrative on slavery or the people they held in bondage. Scholars have found histories in both cases of people who escaped [from] these plantations. Nowhere in the tours, in the materials, on the walls, or in the museums attached to these spaces is that story told. Instead, what we heard at the A.H. Stevens house was how well he treated the people he enslaved, how happy they were, and how good their lives were. He was the vice president of the Confederacy, and is probably most famous for a fiery speech he gave defending secession and the Confederacy on the basis that slavery was just. He said that “the Negro is not equal to the White man” and that “slavery [and the] subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” That is his most famous speech and it’s nowhere to be found at the museum. Instead we get a picture of him as this benevolent figure.

On the Civil War narrative given by a Beauvoir tour guide

“You see, civil war is where one bunch of folk try to overthrow the sitting government and we weren't doing that. We wanted to establish our own country. We didn't care that the North carried on and get along the way they were rolling. That was fine, just leave us alone. Let us build our own country.”

On what Beauvoir says in defense of said narrative

On the one hand they'll tell you that their “state mandate” is to address the period that Jefferson Davis lived here, which is post Civil War 1877 until his death in 1889. On the other hand, we have this entire room devoted to the Confederate soldier and their annual Fall Muster, which is devoted to Confederate reenactments and mock battles that actually never happened. Once we press people on the issue of slavery or the African American experience, one of the responses is that they “don't have enough room on the walls to deal with that.” For me that wasn't a good enough answer.

On the strategy used for the erasure of history

There is this strategy that folks who refer to the Confederacy in this “lost cause” way use. It's [why] they deploy the folks that they believe were "loyal slaves," which they do at Beauvoir. There are a couple of panels on the wall that talk about two formerly enslaved people who came back to serve the Davis’.

On the lies of omission

There are the sins of omission; the 200,000 African Americans who served in the United States Colored Troops, among them my great grandfather. There are the half a million African Americans who liberated themselves before the end of the Civil War. If we're dealing with the post Civil War period in Mississippi then there's a whole lot of lynching, and the stripping African American men of the right to vote, which they won in the Civil War and Reconstruction. This has been a consistent strategy that relies upon [the] co-opting of African American voices to [create] this noble, glorious Confederacy and pre-war way of life.

On a Beauvoir tour guide’s perspective of slavery

“The honest truth is that slavery was both good and bad. It was good for the people that didn't know how to take care of themselves and needed a job. You had slave owners like Jefferson Davis who took care of the slaves and treated them like family. He loved them.”

On the context presented by Confederate museums and sites

I think there is a great example here [in Georgia]: Stone Mountain. It is now much more than simply a Confederate site; it's a public amenity, a park. You have that giant mountain side carving and the Stone Mountain Memorial Association which is still charged with protecting that Confederate monument. It is organized as a site to perpetuate Confederate history; a history that did not occur. So Stone Mountain now has about $13 million in bonds allotted for it, [and] over $200,000 of that money has been dispersed. Now they'll say that's for a resort and conference center, but the money is still going to subsidize a site which is built around an object and an ideology that is corrosive to our democracy.

On the underlying issue of these Confederate monuments

What I'm offended by is the lies that allow some people to perpetuate this idea that certain people are at the center of our history, while other people: black people, Latino people, all sorts of people are at the periphery. That's the problem with this type of funding.

On the impact of this study so far

I think there's a lot of [people] surprised that there's been public money flowing to these sites from the very beginning, and that the public money continues to flow. [There has been] $40 million [spent] over the last decade at least. We certainly missed money at the county and local level spent on statues and monuments. These are public, in public spaces, and many of them are public institutions or state parks.

On what these Confederates monuments should be

If there's public money going to these institutions, then it seems to us that there's an obligation to make sure that the history is being told, and [that] these spaces conform with the facts and don't try to tell a story of the Confederacy that glorifies Confederates [but] completely denies reality of the experience of enslaved African Americans in those very spaces.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457