Section Branding

Header Content

Shark Research Could Help Ga. Shrimpers

Primary Content

The movie “Jaws” famously shows us a shark’s eye view of swimmers in the water, their legs kicking while the shark prepares to attack.

We know that sharks don’t really go after people like the movie’s monster great white. But we still have a lot to learn about how they detect their prey. A researcher at Georgia Southern University is trying to change that.

It turns out, understanding sharks’ senses could help people make a living on the water.Research into sharks' vision and other senses could help Georgia shrimpers.

Shrimpers like William “Catfish” McClain have a shark problem.

“They, well they just attack your nets and they eat holes everywhere in ’em,” he said. “And there’s nothing you can do to get rid of them.”

Those nets are expensive, in the thousands of dollars each, and the sharks cost shrimpers in other ways.

“It hurts us. It hurts the commercial fishermen, because like I say he works for two days, and then he’ll have to sew on his nets for two days. So that’s two days he’s not fishing,” said McClain. “And it causes a lot more work.”

Researchers are trying to help. But first, they need to know more about how sharks see and sense what’s around them. Of course, a shark’s eye exam is a little different from a human’s: there’s no reading letters from a chart or comparing eyeglass lenses.

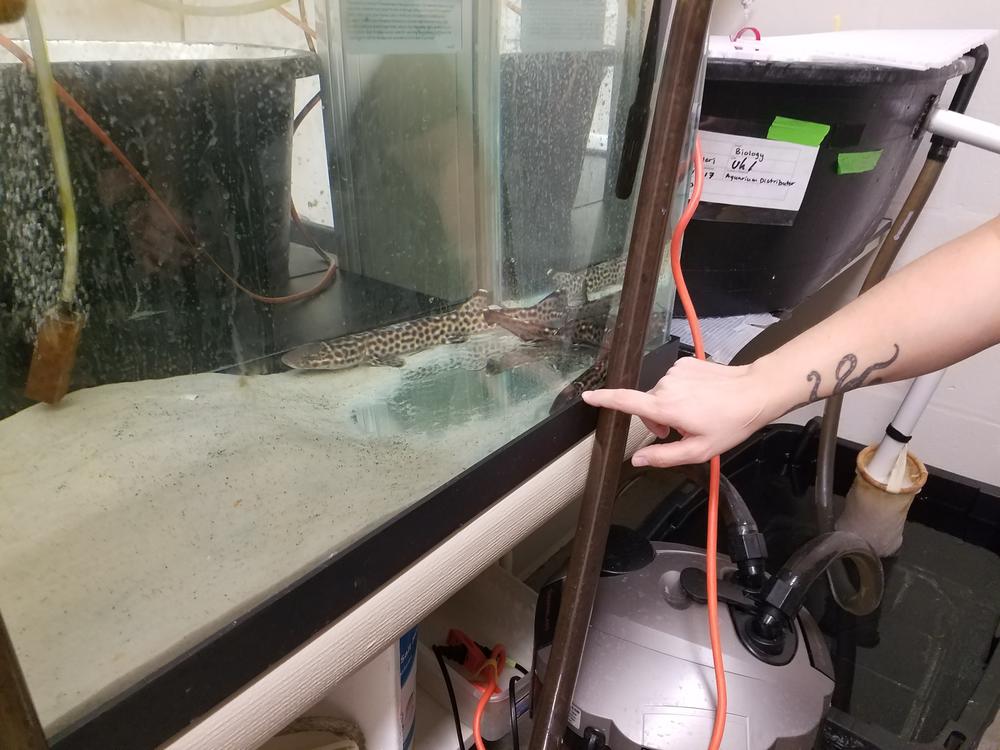

“We can do behavioral testing, where we’ll put the shark and give it different color choices and train it to feed at a certain color,” said Georgia Southern professor Christine Bedore. “And if they constantly go to that color we know that they can see it opposed to the other colors.”

Bedore is a sensory biologist, meaning she studies how animals, specifically sharks and rays, perceive their environment.

“Knowing what colors an animal can see, for example, will tell us why it lives in a particular habitat,” said Bedore. “It can also tell us what they’re seeing in that habitat, so it tells us what stands out when they’re forming images in their eyes and what kind of fades into the background.”

Outside her lab, Bedore also does research on the Georgia Bulldog, a research shrimp boat at the UGA Marine Extension in Brunswick. Shrimper Catfish McClain is part of the crew.

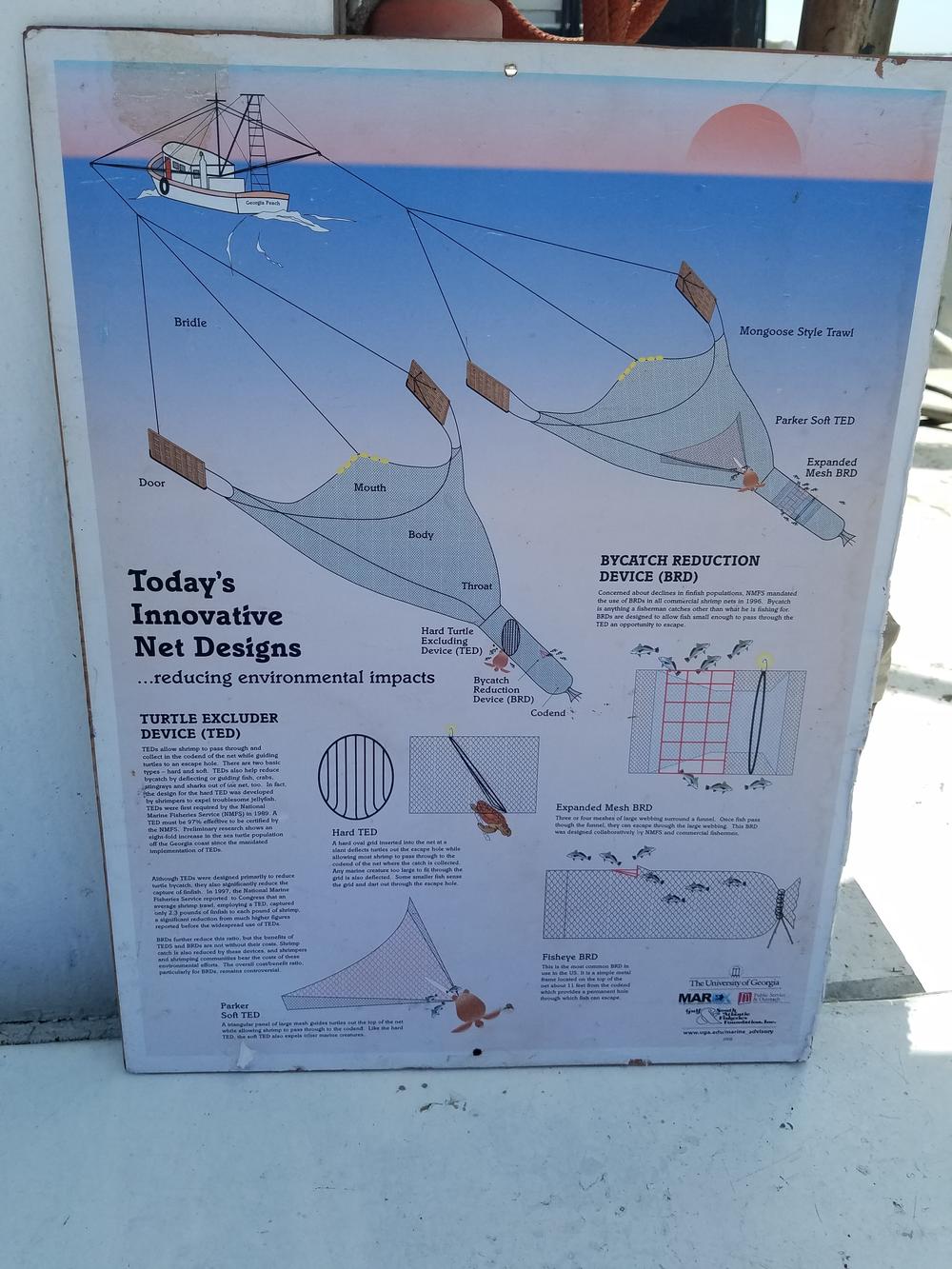

On a recent trip, they brought in small nets called try nets full of shrimp, along with what’s known as bycatch: crabs, fish, rays, and other creatures that get caught up in the same nets.

There’s a lot to learn from these nets, including the health of the shrimp and how many are in a given spot compared to bycatch. Bedore said it could one day help shrimpers with their complicated decisions on just where to cast their nets.

Because sharks can be such a threat to shrimp nets, they factor into shrimpers’ choices as well.

“Some boats will go into water that’s dirtier or muddier and realize that they’re gonna have more work cleaning up the shrimp because they have less shark interaction,” Bedore explained.

Her research could help change that. Sharks can also sense the electric fields created by their prey breathing and moving through the salt water. Bedore wants to make devices for nets and hooks that warn sharks to stay away, possibly using electric signals the sharks can detect.

“We can start developing things that have a lot larger electric field that isn’t signaling to them that there’s prey nearby,” she said.

That might free up shrimpers to go where the shrimp are best. Bedore is working to get grants to help develop the devices.

McClain, who’s been fishing on the Georgia coast for more than 30 years and still owns a shrimp boat, said research like this can be essential for shrimpers.

"It's all about the data, the information. And the studies that these younger kids are doing,” he said. “They're good! They want to figure it out. I'm glad somebody does. We need 'em."

McClain and Bedore both said knowing more about sharks and other creatures can help keep the ocean healthy — and keep Georgia shrimpers in business.