Section Branding

Header Content

Mining Proposal Near Okefenokee Promises Jobs, Raises Environmental Concerns

Primary Content

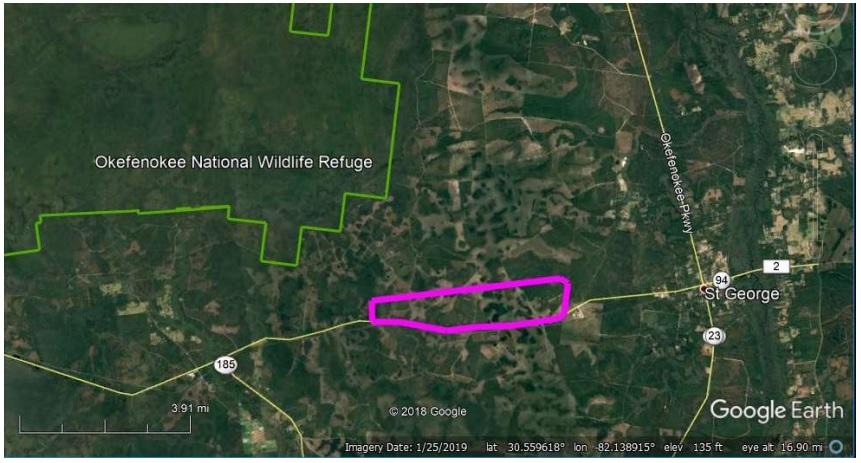

Just above the Florida border, there’s a vast — and famous — swamp: the Okefenokee. It’s more than 400,000 acres of wilderness, with black water, pine and cypress trees, endangered woodpeckers and more.An Alabama company wants to mine for heavy minerals in Southeast Georgia, about four miles from the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. The proposal from Twin Pines Minerals promises 150-200 jobs. But it’s also raised serious environmental concerns.

“You know, one of the things that is so wonderful about this place is the calm, the peace, the quiet, the solitude that people feel,” said Supervisory Refuge Ranger Susie Heisey before an alligator interrupted, sloshing loudly into the water below.

About 15,000 alligators live in the Okefenokee, so many it’s hard not to see one. They are one reason the swamp gets 600,000 annual visits from people all over the world.

“People gravitate to this place. People want to see it, people want to learn about it," Heisey said. “And people want to protect it.”

A proposal to mine for heavy minerals near the Okefenokee is raising alarm for many. They don’t want anything to harm the wilderness.

RELATED: Army Corps Extends Comment Deadline On Mining Near Okefenokee

Alabama company Twin Pines Minerals wants to mine about four miles from the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. The permit application promises 150 to 200 jobs.

Read the full permit application here.

But it has also raised serious environmental concerns. For many, the main issue is the hydrology: what is going to happen to the water underground?

“It’s literally one of those subjects that's out of sight but, you know, that groundwater is really a really important part of the overall hydrological regime of a landscape,” said Chip Campbell, who runs boat tours and rentals at the wildlife refuge and sits on the board of St. Mary’s Riverkeeper.

“We all have to have water: every plant, animal, human, you know, every industry,” he said. “I mean water is absolutely the staple of life.”

Disturbing the ground to dig up minerals could also disrupt what the water does underground, and how much of it there is for the swamp, the rivers and other parts of the ecosystem to use.

There is already heavy mineral mining in the area. The Southern Ionics Minerals mine sits about 11 miles from the swamp’s northeastern edge.

Mining for minerals in sand is different from mining for coal. The mine digs up a relatively small area at a time and separates out the heavy minerals, including titanium and zirconium. It's a bit like panning for gold on an industrial scale.

“All it really is is a series of pumps and pipes and spirals,” said Jim Renner, the manager of environmental stewardship for Southern Ionics. “The heavy minerals are separated from the lighter quartz minerals by the different specific gravity of the minerals.”

The lighter sandy soil goes back into the ground where it came from. Then, they replace the topsoil and replant the trees.

“I have got seven years of hydrologic monitoring data that shows exactly that the temporary dewatering effect of our mine on adjacent areas is indistinguishable from the natural variations of the water table going up and down just due to natural wet and dry cycles,” Renner said.

Twin Pines Minerals said the same is true of the mine they are proposing southeast of the refuge.

“With all the studies that we’ve done, with all of our experts have taken a look at it, they’ve modeled it in very much so detail, and there is assurances that it will have minimal if any effect at all,” said company president Steven Ingle.

“You remember the old trust but verify?” said Chip Campbell. “This is one of those cases where we’ve got to have the verify. We have to have the verification.”

Campbell wants to see Twin Pines’ science before making up his mind.

“If I thought that this was in fact an existential threat to either Okefenokee swamp or St. Mary's River, we would be having a very different conversation and I would be killing them, you know, with the science,” he said.

Steven Ingle of Twin Pines said they would provide their hydrologic reports if regulators ask. A spokesman for the Army Corps of Engineers said the agency wants the reports. Twin Pines said they will be available no sooner than September, according to the Corps.

The public comment period for the project ends Sept. 12.

Even if the hydrology bears out, Charles McMillan of the Georgia Conservancy is still skeptical.

“It's hard to envision something this close of this magnitude next to the swamp that would not have a significant impact,” he said.

McMillan has concerns beyond the hydrology, like the gopher tortoise. They are an important and rare species, not listed as endangered in Georgia but considered a “candidate” for listing. Twin Pines plans to work around the gopher tortoise burrows or relocate them, which Southern Ionics already does at their active mine.

But McMillan says the gopher tortoises could still end up cut off from each other.

“If mining proceeds through there and everybody relocates their gopher tortoises, then pretty soon genetically those communities are going to be isolated,” he said.

And then there’s the question of what happens after the mine is gone.

For some, the Twin Pines proposal for what’s called “reclaiming” the mined land is encouraging: they plan to plant native longleaf pine, the trees that originally grew in this whole area and provide habitat for the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker. That’s instead of the current slash pine and loblolly pine used for timber.

“Usually it’s working timberland and they put it back into working timberland,” said Chip Campbell. “It's a juicy carrot to be sure, to even have the prospect that they, you know, might be part of the longleaf initiative. You know, the restoration of the longleaf pine fire forest.”

Charles McMillan of the Georgia Conservancy calls the longleaf pine a step in the right direction, but only a localized improvement.

“So, you look at you look at a project like this. Site specific improvements, and then landscape impacts, then also maybe even regional when you have something as big as a 400,000-plus-acre swamp,” he said. “If you're looking at impacting the hydrology of that, that's a regional impact.”

It’s an impact that for McMillan would outweigh a few thousand acres of longleaf pine.

He and other advocates are calling for a more thorough environmental review, called an Environmental Impact Statement, before this project’s permit goes forward.

Twin Pines Minerals is hosting two public meetings on their proposal this month, on Aug. 13 at the Charlton County Board of Commissioners’ Meeting Room in Folkston and on Aug. 14 at the Firehouse in St. George. Both begin at 5:30 p.m.

The Army Corps of Engineers is accepting public comment until Sept. 12. Comments can be emailed to holly.a.ross@usace.army.mil or mailed Attn: Ms. Holly Ross, 1104 North Westover Blvd, Suite 9, Albany, GA 31707.

Editor's note: This post has been updated to include the correct location of the Aug. 14 meeting. It originally said St. Mary's.