Section Branding

Header Content

Celebrity, Conquest And Civil War: Steve Inskeep's 'Imperfect Union' Tells A Forgotten American Tale

Primary Content

Millions of NPR listeners trust Steve Inskeep to help them make sense of the news. The Morning Edition anchor manages to sound simultaneously knowledgeable about the facts and curious about the human side of stories — attributes of an incisive interviewer and author.

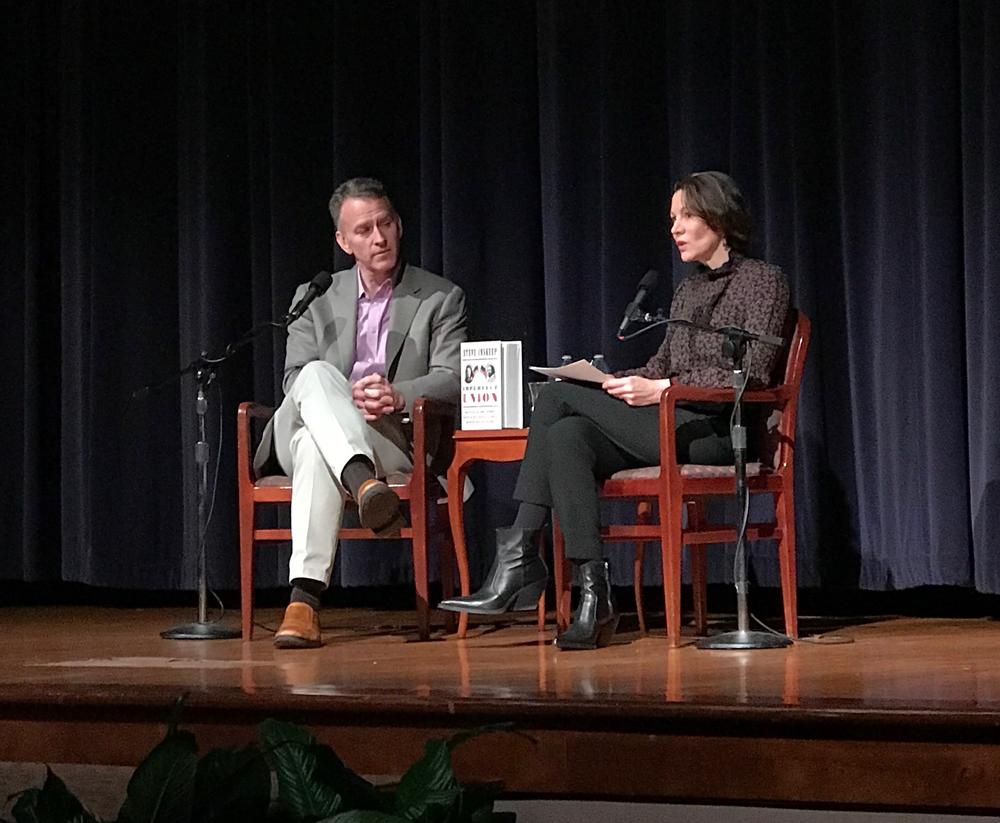

Inskeep’s third book, Imperfect Union: How Jessie and John Frémont Mapped the West, Invented Celebrity, and Helped Cause the Civil War, follows an ambitious couple through some decisive events in American history. On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott spoke with Inskeep about the book onstage at The Carter Presidential Library at an event for A Cappella books.

Imperfect Union tracks the story of John Frémont — namesake of several American cities, towns, streets and at least one casino — and gives equal time to his wife, Jessie, who understood the mechanics of myth-making and used them to elevate her husband in the minds of the American public.

Inskeep paints Frémont as a complicated character whose brazen approach to westward expansion into California left a complex legacy. On some trips, Frémont led his crew to near-starvation; on others, he would lead them to successfully summit the highest mountains he could find.

"This was a guy whose erratic, dreamy decision-making sometimes worked for him," Inskeep explained.

But the story behind his relationship with his wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, casts John's thirst for adventure in another light. Frequently left behind to take care of the children and serve as his political mouthpiece, Jessie reflected extensively later in life on her memories of their life together — and apart.

"It's clear from her writing that this affected her," Inskeep noted. "But she never directly addressed that. And I think from her writing, she believed this was her duty to endure."

Despite some flawed decisions, Frémont also demonstrated moments of "moral courage," particularly when, as a Republican presidential candidate during the contentious election of 1856, he refused to deny the false rumors circulating about him being a Catholic.

"To deny that you were a Catholic while running for president would be to admit that a Catholic should not be president," Inskeep said. "And he wouldn't do it."

Inskeep reflects that though John Frémont is a character full of contradictions, his inconsistencies can teach us something about ourselves.

"There's an incredible complexity to this guy's approach to race and ethnicity and immigration," he shared. "He's for things and against them at the same time. His thinking is not really clear. And we can blame him for that. An in many instances, we absolutely should. But maybe we can also use that as an opportunity to reflect on our own contradictions, and whether our own thoughts entirely agree with themselves."

After the event, the staff at The Carter Center offered Inskeep and the On Second Thought team a tour of the Center. You can find photos of the tour in the slideshow at the top of the article.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On the legacy of slavery in the United States:

"Now, I should say, on this stage, especially, that slavery is everyone's legacy... Slavery is Boston's legacy as much as Atlanta's legacy, because the whole country in some way was involved in the slave economy. And slavery was legal just about everywhere at the beginning of the country. But in the early decades of the United States, Northern states gradually abolished slavery, whereas Southern states more and more aggressively embraced it and saw it as part of their identity as well as part of their economy and part of their society. That became a great divide.

And as it happened, the population of the North grew much more rapidly than the population of the South— that was the demographic change. And that gave the North increasing political power and made people in the South feel more and more insecure. And the capture of territories in the West then created the even more destabilizing question of whether these new territories would be slave states or free states once they became states. And because so much economic power was at stake, as well as political power was at stake, it became a profoundly destabilizing time."

On Jessie Fremont’s journey to San Francisco through Panama:

"You know, it's like 50 miles overland [through Panama], but it was a terrible 50 miles and it was chaos, and there was fever, and there were thousands of people going that way. And so when you get to the Pacific side, there are no ships to take you to San Francisco, because every time a ship would go to San Francisco, and anchor in San Francisco Bay, the crew would abandon the ship and go prospect for gold. There are photos from the 1850s of hundreds of ships just kind of there, just like wrecks, they're just like floating around San Francisco Bay. So it took a while for captains who were determined to round up a crew maybe of disappointed gold miners who'd had enough and get a ship back. But Jessie eventually got out of Panama, eventually got to San Francisco. And she does have this amazing description of what is now one of the most beautiful cities in America, if not the world. But at that time, it's a collection of shacks on treeless hills. The streets were made of boards and the buildings were made of boards. And it was incredibly cold and foggy all the time. And there were fleas everywhere. And you would just sleep anywhere that you could could get. And this was the land of opportunity that had drawn thousands of people from all over the world."

On John Fremont’s expedition into the Rocky Mountains:

"This was a guy whose erratic, dreamy decision-making sometimes worked for him. There was a moment in 1842 when he had one of these expeditions that seemed to have ended a little too boringly for him. And so, he decided – even though he had no orders to do so – to climb the highest mountain he could find. He climbed the mountain with a bunch of his men, they nearly died on the way up. Partway up, they thought they were almost there, and so they left behind their food and their supplies and their coats, as one does when climbing a mountain.

They got there, planted an American flag on top, and Freemont looked around and decided this must be the highest place in all of North America — which then became part of his legend that he had surmounted the highest point in the Rocky Mountains. It is known today as Fremont Peak… it is not among the 100 highest mountains in North America. But he was a legend for having done this thing that was the rough equivalent of its time of the moonshot.

On Fremont’s decision not to deny being Catholic during the election of 1856:

Steve Inskeep: Fremont did not want to deny being a Catholic because to deny that you were a Catholic while running for president would be to admit that a Catholic should not be president. And he wouldn't do it.

Virginia Prescott: And you identify this as possibly the most courageous thing he ever did.

Steve Inskeep: I think so. This is someone who'd shown a lot of physical courage, but this was a moment of moral courage. And there are all these contradictions – and that's true of all of us in a way, isn't it? This is a guy who celebrated the diversity of America. He writes about the incredible variety of his expeditions… and he was proud of that… but would also speak of Indians, including the ones who worked for him, on whom his life depended, in a very patronizing and racist way. There's an incredible complexity to this guy's approach to race and ethnicity and immigration. He's for things and against them at the same time. His thinking is not really clear. And we can blame him for that. And in many instances, we absolutely should. But maybe we can also use that as an opportunity to reflect on our own contradictions and whether our own thoughts entirely agree with themselves and make sense.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457