Section Branding

Header Content

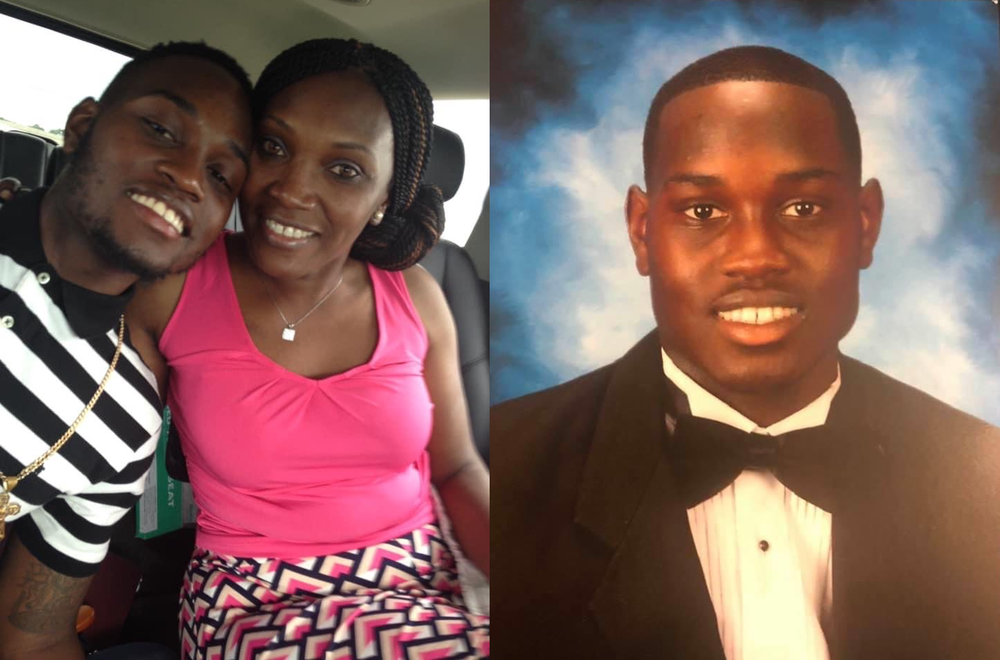

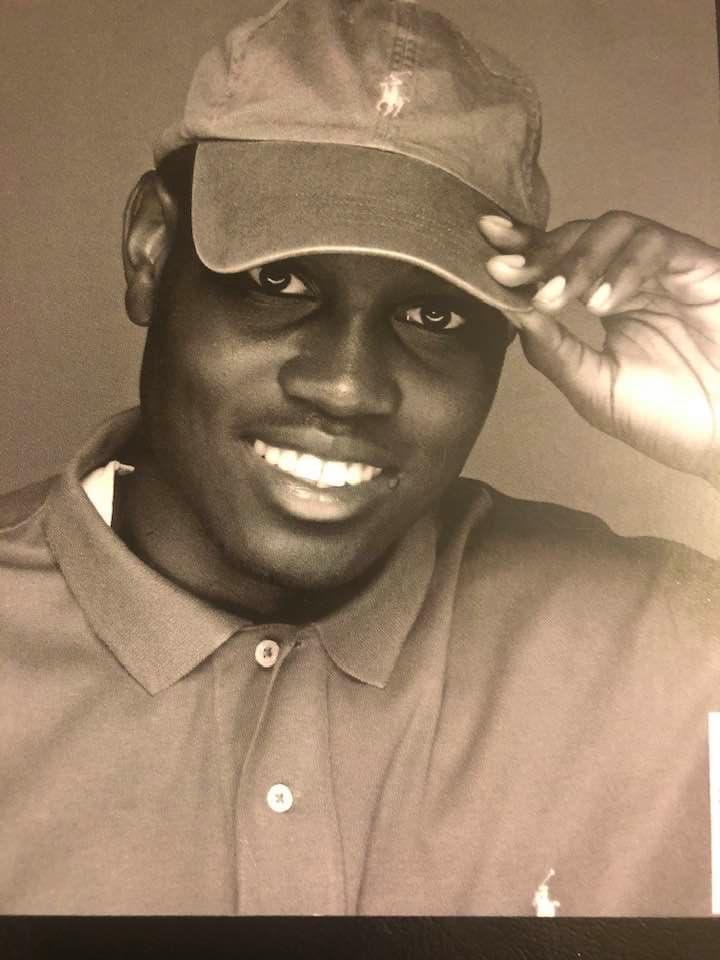

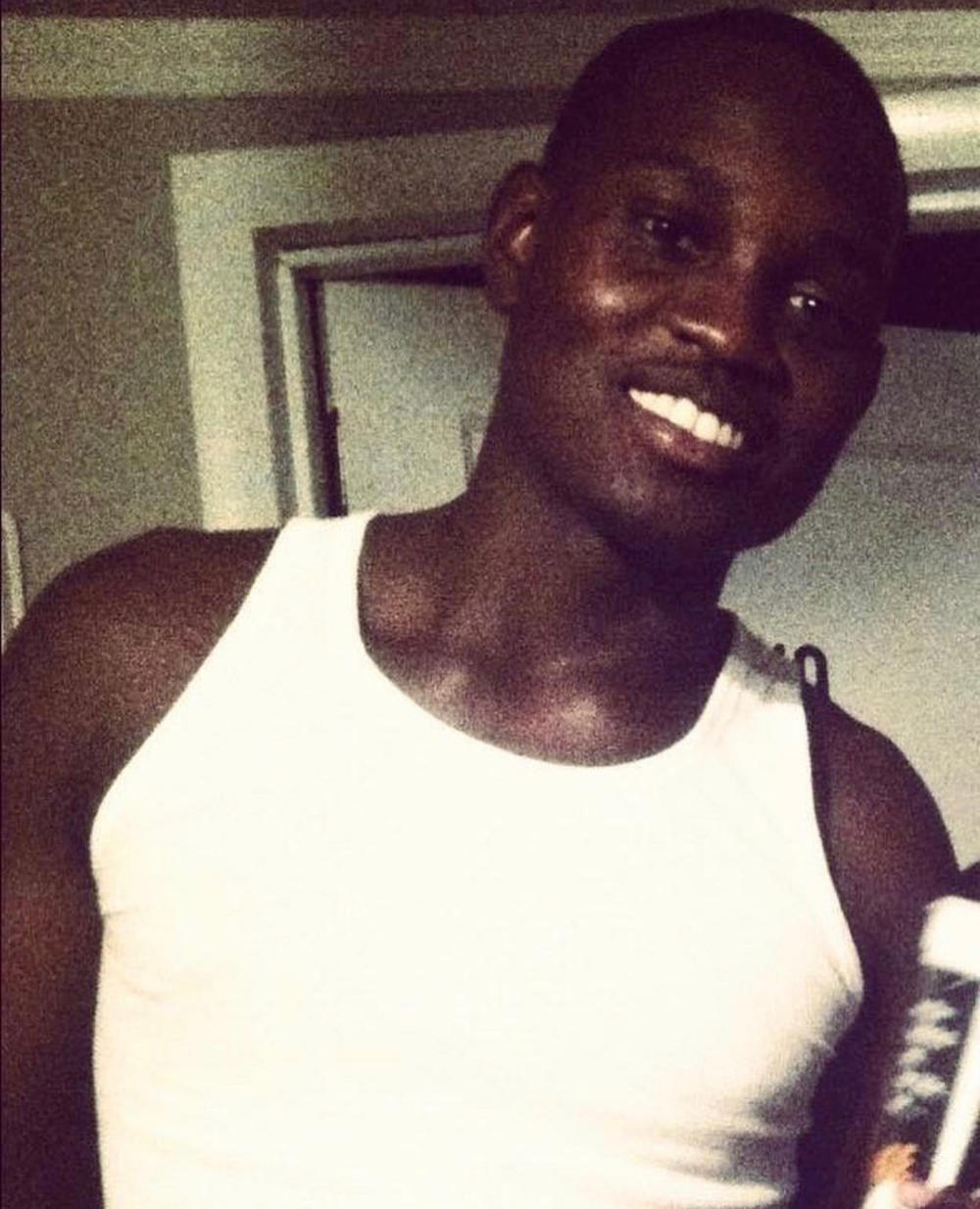

Ahmaud Arbery's Family, Friends Reflect On His Life, Death And The Path To Justice

Primary Content

The last 35 seconds of Ahmaud Arbery’s life have been viewed, studied, dissected and discussed all over the world. That’s because of a video that went viral, showing his final moments before he was shot on a shady street in Satilla Shores, Georgia on February 23.

And while his death has made international headlines, the people of his community remember Arbery for how he lived.

His mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, is one of them. She shared that her son was well-mannered and respectful, a young man who loved running, video games and writing lyrics for raps.

“He loved me, and I loved him,” she said. “Ahmaud was good.”

Cooper-Jones joined On Second Thought – along with Arbery’s close friends Akeem Baker and Demetris Frazier and his former football coach Jason Vaughn – to reflect on Ahmaud Arbery's life and death, and the injustices that followed. Jim Barger Jr., who wrote an article for The Bitter Southerner about the history and response of the community, also joined the conversation.

“He was one of those friends who did not tell me things I wanted to hear, but things I needed to hear,” Baker recalled. “He was that type of friend – never the friend to steer me in the wrong direction. And if I did fall astray or go on the wrong track, he was the type of friend to just [say], ‘Hey man, you could do better; this is not you. Stay true to who you are.’”

After Arbery’s death, Cooper-Jones says police told her that her son was involved in a burglary, that there was a tussle over the firearm and, as a result, he had been shot and killed. That news came as a shock to his mother.

“I was just numb. I was feeling nothing,” Cooper-Jones explained. “To be honest, I can't really describe the feeling because I never felt anything like it before. [The story of what happened] didn't sound right, but at the moment, I had to deal with [the fact that] I had lost my baby boy.”

The incongruities between the police’s story, the news reports, and how Arbery’s friends and family knew him began to raise suspicions.

“For [Arbery to be killed], it definitely took a toll on everybody. It hurts bad,” Frazier said. “But at the same time, we knew it just didn’t seem right. So, we got together and told ourselves that we will make a promise to ourselves to try to find out the truth.”

Cooper-Jones spent a week dealing with grief and funeral arrangements. Then, she started making calls. She discovered through Facebook that the District Attorney that was on the case by that time, Ware County’s George Barnhill, had a son who had previously worked with Gregory McMichael – and she demanded that Barnhill recuse himself.

“I knew if I didn't do something and do something quick, the case was going to go away,” Cooper-Jones said.

RELATED: GBI Says Further Arrests Unlikely In Arbery Shooting

The video displaying the altercation and shooting that ended Arbery’s life was released in early May, showing a much different narrative than what had been told to Cooper-Jones, and rocketing the story into headlines and households across the nation. It also prompted intervention from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Then, on May 8 – Arbery’s birthday – hundreds of thousands of people across the nation (and some internationally) used the hashtag #IRunWithMaud and went for a 2.23 mile run – February 23 being the day he was killed – to show their support.

Since then, there have been three arrests in the killing of Ahmaud Arbery. Those include the men in the video – Gregory and Travis McMichael – who are shown cutting Arbery off as he jogged, and shooting him multiple times with a shotgun. And on Thursday, police arrested a third man, William “Roddie” Bryan, who filmed the video of the fatal shooting.

But these arrests came months after Arbery’s death, only after outrage in the local community transformed into a national and international uproar – magnified by the footage of what really happened.

This new evidence was in direct contrast to Barnhill’s April statement, in which he wrote that there had been no grounds to arrest the McMichaels – that they were “following, in ‘hot pursuit,’ a burglary suspect, with solid firsthand probable cause.”

“That document will go down in history, I hope, as one of the worst examples of manipulation of the legal system that we've ever had,” Barger said.

And even without the case being heard in court, the events and timeline so far have already damaged the community’s perception of its officials.

“I can honestly say: I didn’t know how bad it was,” added Coach Vaughn. “I just didn’t see that coming from Glynn County – I didn’t – but obviously there is a problem.”

According to a 2016 survey from the Pew Research Center, roughly 75% of White people say police in their communities do a good job when it comes to use of force, equal treatment, and accountability. That number drops to around 33% when asked of Black communities.

Frazier says that the handling of Arbery’s death only compounds that suspicion and skepticism in Brunswick.

“I think it is going to take a lot for me to gain that trust, especially being a young Black man seeing this happen to Ahmaud, and the way it went down,” he said. “I think it is definitely going to take a lot for not only myself or Akeem [but also] any of the parents that have kids, young Black men, in this community. It’s going to take a lot for them to trust law enforcement again.”

For the nation, Arbery’s death has reignited conversations about racial profiling and racial injustice. Baker points out that, for Black communities, these conversations are part of daily life.

“Ahmaud and I, we shared conversations about racism and being racially profiled,” Baker said. “And we both understood that our skin was considered a weapon – our Blackness was considered a weapon – when it should not be.”

And that is underscored by the video of Arbery’s death, which has caused horror and pain across the world – a trauma most deeply felt by the community that now mourns him.

“I was heartbroken to see my friend being hunted down and killed like some animal,” Baker said. “Some days I wake up just crying because clips keep replaying in my head of how he was, you know, fearing for his life and fighting for his life. It was like a clip from the 1920s, in the Mississippi Burning movie or something like that. This is 2020 and this is still happening to Black souls. It’s just terrible. It was just an act of pure evil. And everyone involved, they just need to be held accountable to the highest degree.”

For those who knew Arbery, anger, frustration and grief have fueled their drive to demand justice and accountability for his death.

“Running for Maud – it pulls me out of, you know, feeling down; it pulls me out of my bad days, my bad hours,” Coach Vaughn said. “You know it’s giving me a smile right now, to know I’m going for my guy. 2.23 on the 23rd – I need you guys to run for my guy! Post it and show it! We’re not going to forget about my guy!”

And that also goes for a grieving mother, who has been thrust into the spotlight.

“My mindset is to get justice,” Cooper-Jones said. “The day that they laid my baby to rest, I gave him the promise, and that promise was: ‘I will handle this, son.’ And I will keep that promise. I have to keep pushing.”

RELATED COVERAGE

- GBI Arrests Man Who Filmed Ahmaud Arbery Shooting

- Leaked Video Of A Deadly Shooting In Coastal Georgia Sparks National Coverage

- Georgia Lawmakers Call For Passage Of Hate Crime Law And End To Citizen's Arrest

- Ahmaud Arbery Case Puts Spotlight On Community's Race Legacy

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On worrying more for Black children in public

Vaughn: When I see white kids playing outside, having a good time, I smile. I see them riding their bikes and I feel good, because I feel like I'm in a great community. But when I see African American kids playing around, I gotta say a silent prayer. You know, I got to hope that nobody disturbs them, nobody comes up to them, nobody harasses them.

On communities needing policing agencies that will enact justice

Vaughn: I'm a football coach, so I have players that are Black, I got players that are White. And at the school, we just kind of get along. The community overall is a good community; I wouldn't live here if it wasn't. But even in good communities, there exist people who are unfortunately hateful — for whatever reason. And the men that did this were extremely hateful men. And every community has to deal with hate and people like this. And we should have a policing agency in place to deal with people who act out on hate. And in this case, that did not happen. A football coach and two best friends [Baker and Frazier] were turned into advocates to get people to listen, to try to get support for Ms. Wanda and her family. We literally jumped into the game to support the family. That should not have had to happen. Something should have been done immediately.

On how Wanda Cooper-Jones gave her son “the talk” about being a Black man in America

Cooper-Jones: Of course we'd had the talk. Ahmaud was my baby but he then grew to be a young man, a young adult that began to drive. And we really had the talk when he got to the age where he was driving, because if he was driving off, I wasn't there to protect him. So we had several, several conversations about how to conduct himself if he's pulled over. I never worried about him being not mannered — because he's gonna respect those who respect him. So I never worried about him on that part. But I told him, you know, you are African American and you are in south Georgia, so please be careful.

On the relationship between the black community and the Glynn County Police Department

Baker: I never really fully trusted the law enforcement here in Brunswick, so I was always kind of skeptical about the way that they handled things and, you know, [...] their protocols and procedures. So I've never really fully trusted the police department; Ahmaud never really fully trusted them as well. So the things that have happened, in terms of this case, is not shocking. I've always felt uneasy from the time that I found out about my friend's death. I always felt like there were certain answers that probably were not given to us in terms of seeking the truth. There's always been a lack of trust with the Black community and the police department.

On modern day profiling of Black teenagers on his football team

Vaughn: We get out of practice at around 7 o’clock, so my kids are going to walk home, [and] there's gonna be about eight of them. My players was coming back to me saying, “Coach, we were walking home and a police officer pulled up to them and said, ‘Are you guys a part of a gang? Did y'all break in to something? Did y'all steal anything?’” And I go into coach mode on them first like, "Okay, so what were y'all doing?" and they're like "Coach, we was just walking" [...] And I feel bad as a coach because I really don't have an answer for them. I don't know what to tell them. They literally was just walking home from practice, and a police cruiser literally pulled up on them and asked them if they were in a gang, where they walking, where they going, what are they doing and everything else. And I hear these stories and, I hate to say, I hear it a lot. And I just don't have any real answers for my football players because, I mean, what am I supposed to say? Walk slower? Walk faster? I don't know how to tell them not to be harassed. You see what I’m saying? I can't explain it to them.

On how the public can best support the family

Cooper-Jones: Just stand with us. Just go out into the community, make sure everybody's aware of what's going on, what needs to go on. And just stand with us until we get through this. And as a community, as a city, we will get through this. And losing Ahmaud, it has shown that we didn’t love enough. We need to love more. We need to care more.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457