Section Branding

Header Content

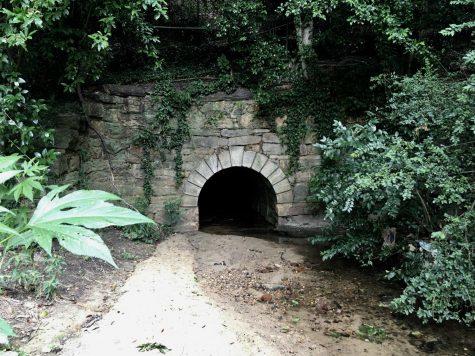

Historic Macon Railroad Viaduct Gone But Not Forgotten

Primary Content

For the last 121 years, a historic brick railroad viaduct lay below the College Street bridge.

Nearby neighbor Ryan Griffin, who has a penchant for historic preservation, said he didn’t even notice it until he bought the commercial building next door a couple years ago.

“It was a very cool little brick bridge. It was very neat and most people probably didn’t realize it was there,” Griffin said Friday.

He’s using the past tense because the arched structure was taken down this week to make way for a taller bridge to accommodate double-stacked freight cars on Norfolk Southern Railroad’s rail transportation network.

“It’s a shame that structures like that have to be taken down,” Griffin said. “But it’s a sign of progress, right?”

It wasn’t until contractors working for the Georgia Department of Transportation removed trees off Chestnut Street that the 1899 structure really could be seen.

Cayley Champeau, a GDOT senior transportation historian, knew the viaduct was doomed when she began working on this project.

“Sometimes when we start and we know something is slated for demolition it’s hard because, as historic preservationists, we’re trying to save things,” Champeau said. “Unfortunately, this one couldn’t be saved.”

In addition to needing more height for railcars, as was the case with the recent raising of the Pio Nono Avenue bridge near Roff Avenue, the College Street bridge had structural deficiencies, according to a GDOT news release about the project.

Antique crisscross motif steel railing in diamond-shapes was deemed insufficient and unsafe for pedestrians and vehicles on the thoroughfare that joins downtown with Mercer University.

When talking about its historical significance, Champeau had to keep reminding herself not to call the brickwork a bridge.

“It’s interesting that it’s a viaduct. We don’t come across those very often,” she said. “It’s technically too short to be a bridge.”

GDOT commissioned a Historic American Engineering Record for the viaduct to document its history for posterity.

Historian Amber Rhea, of Atkins North America Inc., included the original blueprints prepared by Edge Moor Bridge Works in Wilmington, Delaware, in the report compiled with Champeau. Edge Moor was founded in 1873 and operated until 1900 when it was acquired by J.P. Morgan’s American Bridge Company.

Aside from some grafitti, the viaduct with a Romanesque Revival style masonry arch, remained substantially intact below the heavily traveled road.

“Elements of the Romanesque Revival style include protruding bricks and corbeling that forms an arch with decorative pendants,” the report reads.

Corbeling is staggered, stacked bricks that jut out from the wall as a type of bracket or support.

The bricks were laid when the Central of Georgia Railway was in its heyday with rail lines from all over the state converging in Macon’s hub.

“It appears that masonry arch technology may have been used earlier in the construction of railroad infrastructure, with steel and concrete coming more into favor as the late 19th and early 20th century progressed,” the report stated.

Few masonry arch structures remain, but you can find others in Macon.

Two of them pre-date the College Street viaduct – an early 19th century stone drainage culvert under the railroad tracks at the back border of the Macon Dog Park near Linden Avenue and the 1870 brick semicircular arch overpass supporting the former Central of Georgia tracks at the Ocmulgee Mounds National Park. Near the entrance to old Central City Park, a 1915 brick segmental arch overpass carries the rail line over the westbound lane of Riverside Drive.

Champeau believes these archways were relatively common during the time period.

“I believe that there were probably ones around the U.S., just not very many left, unfortunately,” she said. “This one at College Street was a really nice one. It’s beautiful.”

The historians’ work verifies the viaduct would have been eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. It was located within Macon’s Historic District, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

“Residential development began in this area after the 1871 establishment of Mercer University,” the report states. “Historic brick street pavers are visible at the intersection of College Street and Chestnut Street. A variety of architectural styles, including Italianate, Queen Anne and Folk Victorian are prevalent in the area, which remains largely intact and retains a high degree of integrity.”

Although the viaduct is forever gone, its story will live on, which is the goal of Champeau’s work.

Historic Macon Foundation executive director Ethiel Garlington’s property practically backs up to the railroad tracks close to the old viaduct.

“Someone turned me on to it years ago,” Garlington said.

He has been involved with the federally required mitigation process to compensate for the loss or diminishment of a historic property.

Although he laments losing such a significant structure, Garlington has been aware of the safety issues while walking the neighborhood with his young children.

“From a pedestrian perspective it was harrowing and dangerous. That was one of our biggest points in the mitigation,” Garlington said. “We wanted to make sure that what went in was compatible with pedestrians. What’s going in is going to be much safer.”

Champeau said, “It’s a constant balance trying to protect appropriate things while also ensuring safety and delivering on our projects.”

To be more appropriate for the historic district, they came up with a design featuring bits of brick on the inside panels.

It was also one of Champeau’s goals to salvage some of that 19th century brick.

“They couldn’t guarantee they could save any of the bricks but we did ask them to save as many as possible,” she said.

Part of the mitigation is to create a new greenspace on the now-empty lot between College and Chestnut streets.

Salvaged bricks can be used there when a bench, bus shelter, light post and trash receptacle will be installed along with two interpretive panels tracing the history of the railroad and the old viaduct.

“I’m really glad to hear people are really interested in learning more of the history. It was a really cool viaduct,” Champeau said. “I think the new bridge will be beautiful, too.”