Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Cities Confront Confederate Monuments

Primary Content

As demonstrations continue nationwide over police brutality and systemic racism, many are calling for monuments honoring the Confederacy to come down. The monuments have become flashpoints for protesters and targets for vandals.

But current Georgia law prohibits moving the monuments in most cases. That creates a challenge for cities across the state.

In Athens, the county commission was set to vote Thursday on whether to move a Confederate monument away from downtown.A look at how Athens, Macon and Savannah, Georgia are confronting their Confederate monuments and handling calls to bring the monuments down.

Steps away from the University of Georgia is a tall obelisk etched with the names of fallen Confederate soldiers from Athens. Spray-painted over the names are anti-police slogans, still visible even after the local government tried to clean them off.

Protesters have gathered there for weeks. Camila, who preferred not to give her last name because she said she has been threatened, was one of the peaceful protesters who local police tear-gassed on May 31 in front of the monument.

“I decided to come back out here and singularly protest with my picture of Dr. King as a reminder to keep the peace,” she said. “And I was, to my complete surprise, joined by about 100 people throughout the day who also felt the same sentiment.”

The mayor and county commission are considering relocating the monument.

“This is one small step we can take to remove the iconography of the old South that has allowed subordination of Black lives to exist for so long in this country,” said Commissioner Russell Edwards during a June 2 meeting. “I’ve had enough.”

Athens-Clarke County government officials are now proposing to move the monument in a way they say still follows state law.

Confederate monuments can be moved for things like construction, so they are planning to expand the existing crosswalk where the monument stands. If the project passes, the monument will be moved to the end of Timothy Place, the only area in Athens with ties to a small Civil War battle.

The commission was set to vote Thursday.

But that won’t end the fight over the monument. The Athens chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans is suing, claiming that moving the monument threatens the group with “immediate and irreparable injury.” The government has until July 15 to respond.

One of Macon’s Confederate statues is an anonymous soldier atop an obelisk at the foot of Cotton Avenue. There’s an effort to convince the county government to move the statue. The monument was recently vandalized with gaffiti, which protesters and activists disavowed.

The activists said graffiti is not going to further the conversation. So to give people a nondestructive way to alter the meaning of the statue, they boxed it in with an 8-foot-tall plywood canvas.

Now the box is dense with painted expressions of Black pride.

The effort was organized by artist Tiara Ponce. She said art like this and the conversation it encourages are part of what she called training a culture.

“This is teaching love. The culture of love. The deficit is the conversation. The conversation has not been had. ... I’m not gonna say the bear hasn’t been poked, because that’s literally not it,” Ponce said.

“It is, OK, this is here,” she said, indicating the statue. Then, noting the box artwork at its base, she said, “OK, this is here. Now, let’s have the conversation.”

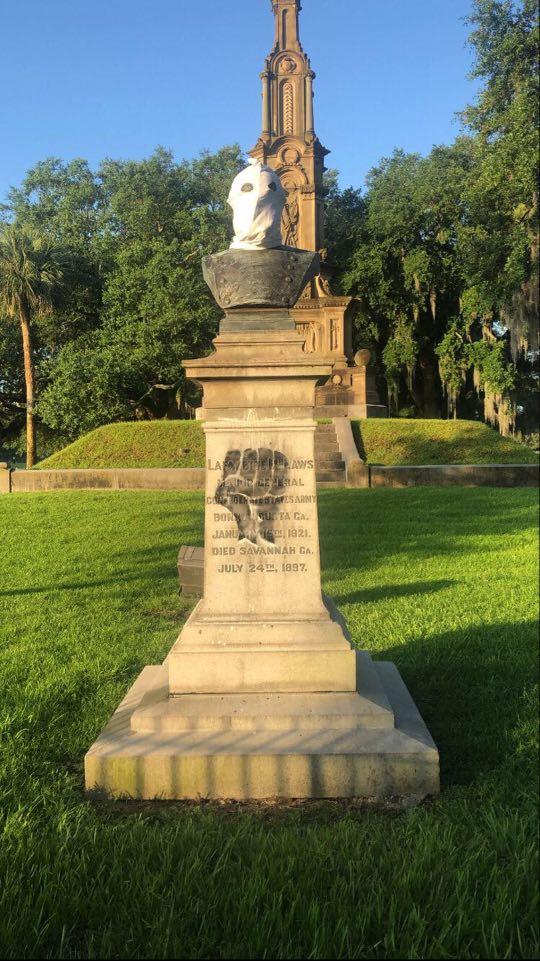

Savannah’s tall stone monument sits in the heart of popular Forsyth Park, on top of a high mound so it towers over the trees and the flat landscape. To Anita Narcisse, who started a petition calling for the monument’s removal, it sends a clear message of white supremacy.

“Don't forget that we still have power over everyone else, you know?” Narcisse said of the monument’s message. “So it definitely feels like, you know, this ominous looming vibe that people really do uphold those values still.”

But Savannah Mayor Van Johnson told GPB’s On Second Thought that he sees the monument differently.

“I don't look at them in terms of hate,” he said. “I look at them in terms of, of overcoming. Here I am, the mayor of this city. Here I am, years and years later, showing that we were able to overcome.”

Johnson said he’s more focused on policy change.

“I think it's more important for us to get rid of the monuments of structural racism, in terms of our practices, policies, ordinances and laws that keep people living in Confederate times,” he said.

Narcisse agreed that a lot of real-world policies need to change. But they said the monument sends a message that Black people are not really safe here. And for Narcisse, that’s just as real, and important.

“I was talking to my dad the other day and he was asking me why I'm putting so much energy into this, and I told him I was like, you know, I just want Black people to be treated better, and I want them to feel safer,” Narcisse said. “And he will be 70 this year. And he said, ‘I don't think something like that will happen during my lifetime.’”

That’s why Narcisse said change cannot wait, on symbolic or structural racism.