Caption

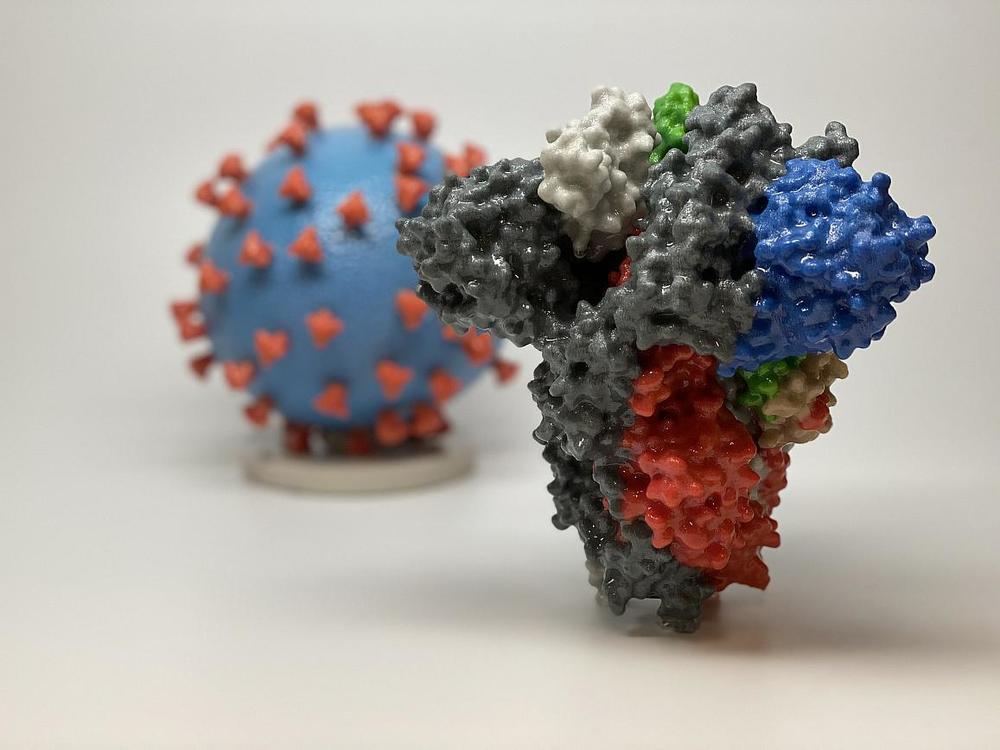

3D print of a spike protein of SARS-CoV-2—also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19—in front of a 3D print of a SARS-CoV-2 virus particle. The spike protein (foreground) enables the virus to enter and infect human cells. On the virus model, the virus surface (blue) is covered with spike proteins (red) that enable the virus to enter and infect human cells.

Credit: NIH