Section Branding

Header Content

George Floyd's Third Ward: Reflections On The Neighborhood That Made Him

Primary Content

In 2002, On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott recorded stories of residents from the Houston neighborhood where George Floyd grew up. Virginia reflected on the rich cultural legacy of the historically African American community.

George Floyd was laid to rest in Pearland, Texas earlier this week. He was buried next to his mother, known as "Miss Cissy" in Houston's Third Ward, where Floyd grew up. Beyonce and Solange Knowles were also raised in the neighborhood. So was the actor Phylicia Rashad, the director and choreographer Debbie Allen, and musicians Samuel John "Lightnin'" Hopkins and Jason Moran.

Reflections on the neighborhood that made George Floyd.

It's a neighborhood I came to know well as a visiting artist at Project Row Houses beginning in 2002. The non-profit uses art, design and community collaboration to preserve the identity of Third Ward, which is slowly gentrifying. Still, the area around the Cuney Homes complex where Floyd lived remains one of Houston's poorest. The median income there is less than $20,000 dollars. Jack Yates High School - where Floyd played basketball and football - received a D rating from the state last year.

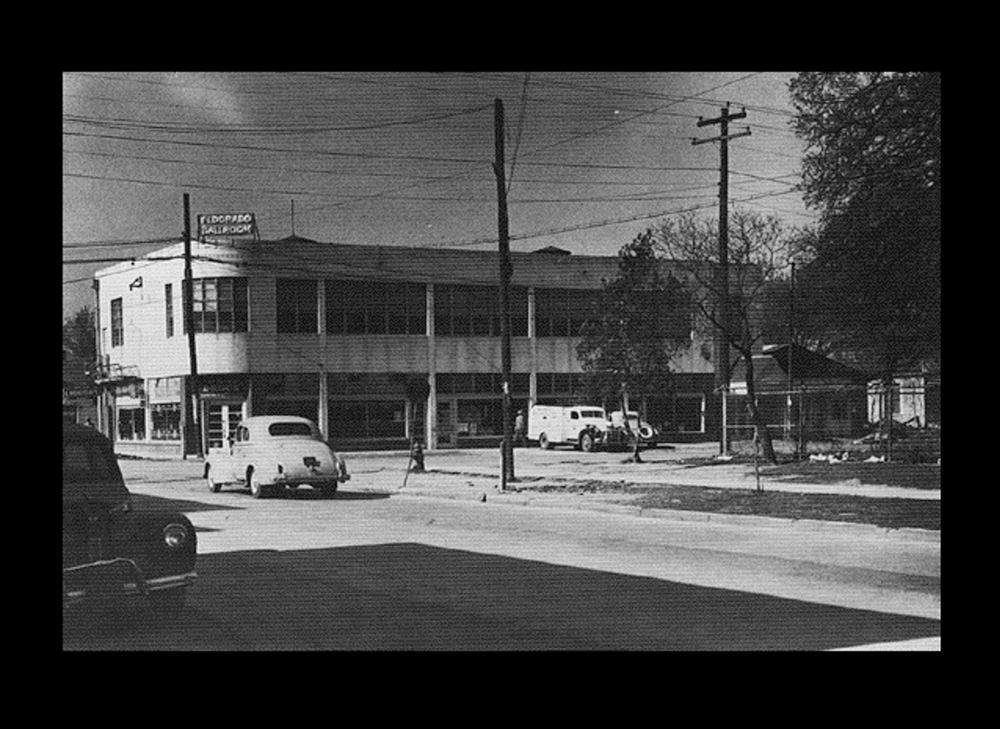

But from the mid-1930s to the late-1960s, Third Ward's North Side was a bustling center of African American economic, social and civic life. Stores, restaurants, shops and the elegant El Dorado Ballroom lined its main thoroughfare, Dowling Street. That was before integration, public works projects and urban renewal programs - and decades of public disinvestment - left Third Ward a shell of its former self.

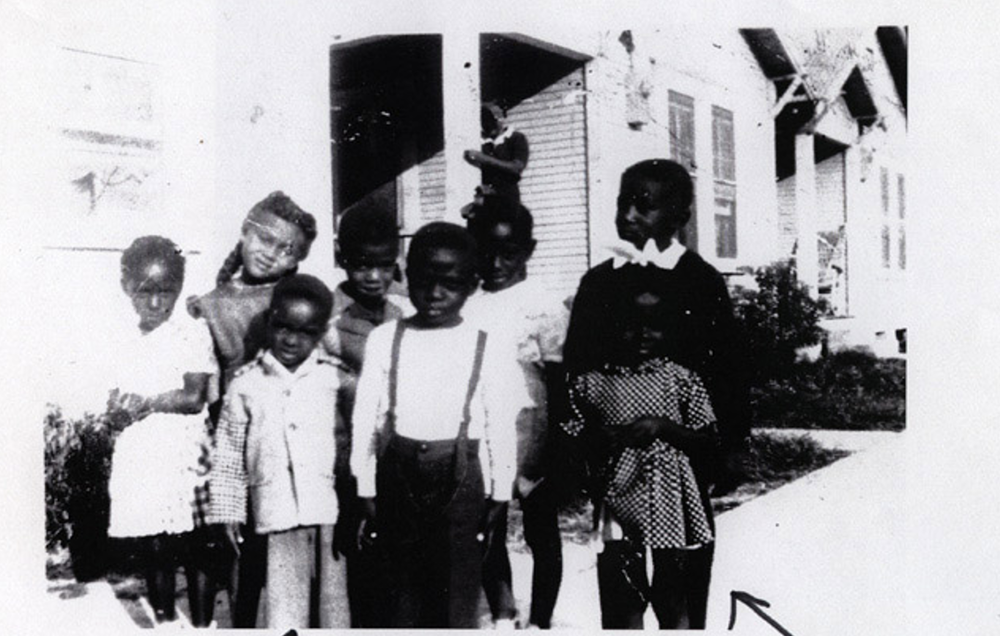

I taught students in Project Row Houses' after school program how to record the stories of the neighborhood as remembered by their parents, grandparents and neighbors who witnessed its heyday, like longtime resident Ernie Atwell.

"It was a 24-hour street, Jack!" Ernie told us. "Folks walked up and down [Dowling] Street. There was live entertainment, a lot of beer lounges, the El Dorado! That was the biggest thing blacks had ever seen. It was humming! There are one or two things that could happen to you [there]: You either made it with a lady or got yourself killed."

The kids and I edited the recordings and turned them into a sound installation at Project Row Houses. We cobbled together a "listening room," where visitors could sit and hear oral histories of the neighborhood.

The memories people carried of their lives in Third Ward were strikingly different than the neighborhood my students lived in. We used their first-person perspectives as departure points to look more deeply into the past. We followed the migration of people like Mississippi-born artist Cleveland "Flower Man" Turner, who came to Houston from the rural south to find jobs and became part of Third Ward's rich communal and cultural life.

Together, we learned about the history of redlining, and other discriminatory lending policies, and about federal and state highway projects that disproportionately targeted black neighborhoods across America in the 1960s and '70s. That pain was particularly felt in Third Ward when Interstate 45 and later state highway 288 carved up the Third Ward. Those projects displaced hundreds of black homeowners and turned remaining homes into rental properties. Preston Seymore told us that his family was left behind as people were forced out in droves.

"All I could see is people were leaving," he said. "And they weren't leaving one at a time. They were leaving bunches at a time."

Then, after decades of suburban white flight, downtown living became fashionable again in cities across the country. In the late 1990s, Third Ward began filling up with dense new apartment blocks that dwarfed the old shotgun houses. Flower Man shared his fears that those developments would take over.

"Sooner or later, it's going to spread and the closer it gets, you take a house and if it doesn't meet the climate up to these apartments and everything, they’re gonna bulldoze it down," he said. "And these people around here ain't gonna be able to do anything and they’re gonna sell out."

Flower Man died in 2013, but his home - covered in mirrors and found objects - was a destination for tourists in Third Ward and documented in books about Southern Vernacular Art. People also visit the home where Beyonce grew up blocks away, and the site on Dowling Street (now Emancipation Avenue) where Carl Hampton, leader of the Houston chapter of the Black Panther Party, was shot in a standoff with police in 1970.

It was clear to me that there was something extraordinary about Third Ward, even though I was a relative tourist myself. Alvia Wardlaw grew up there on the campus of Texas Southern University. Her father was a professor at the HBCU. Alvia has had a dazzling career in the arts and is director of the University Museum at TSU. She is an unflappable resident, de facto historian and booster for the Third Ward. Alvia says that despite growing gentrification, there are things in the neighborhood that aren’t going to change.

"People just know each other. They hang out together. They speak to one another on the street," she said. "There's an informality to life here. It's very refreshing. That's what I wanted for my son."

Alvia was in a reflective mood when I reached her at home watching George Floyd’s funeral. She and her friend, photographer Earlie Hudnall, had been wondering if they'd ever seen the aspiring young football player at TSU's annual homecoming parades. Both assured me that if George Floyd lived at the Cuney Homes, he had definitely heard TSU’s famed Ocean of Soul marching band rehearsing on campus. Alvia says that sound "was just your heart beat... the drums, the brass. It’s those kinds of things that were Third Ward."

"Memories and traditions anchor us," Alvia continued. "So when Beyonce mentiones 3rd Ward in her lyrics, you know, 'always coming back to H-town.' When Jason Moran, the pianist, talks about growing up in the Third Ward, it's something that is really, really felt."

That feeling is palpable in the community George Floyd came from and then left when he headed to Minneapolis looking for a fresh start three years ago. When he returned to Houston in a gold-plated casket, thousands of masked mourners and millions of network and cable viewers looked on. The service was partly a celebration of his life and impact as a brother, father, mentor and son in the community. And it was part denunciation of his horrific death - while pinned on the ground by Minneapolis cops. The brutality of that death set off a global movement to protest police violence and a national reckoning with institutional racism that has concentrated poverty in historically black neighborhoods across America.

Now George Floyd is part of another local landmark; two new murals depicting him have been added to what’s known as "The Wall." It’s an improvised memorial across from Cuney Homes, where residents have for years painted the names of the dead. "There’s a lot of names up there," Earlie told me. Both he and Alvia have visited the side-by-side murals to pay their respects. Alvia says it's become a pilgrimage site for families, journalists and fans of "Big Floyd," as he was credited on a mixtape with chopped and screwed hip-hop pioneer D.J. Screw.

On "The Wall" is an image of George Floyd, the man Reverend Al Sharpton called "an ordinary brother who changed the world," painted with angel wings and a halo above his head that reads, "forever breathing in our hearts."

Next to it, are the words: "Texas made, Third Ward raised."

Virginia wishes to thank the staff and students at Project Row Houses after school program and the many residents of Third Ward who shared their stories.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457