Section Branding

Header Content

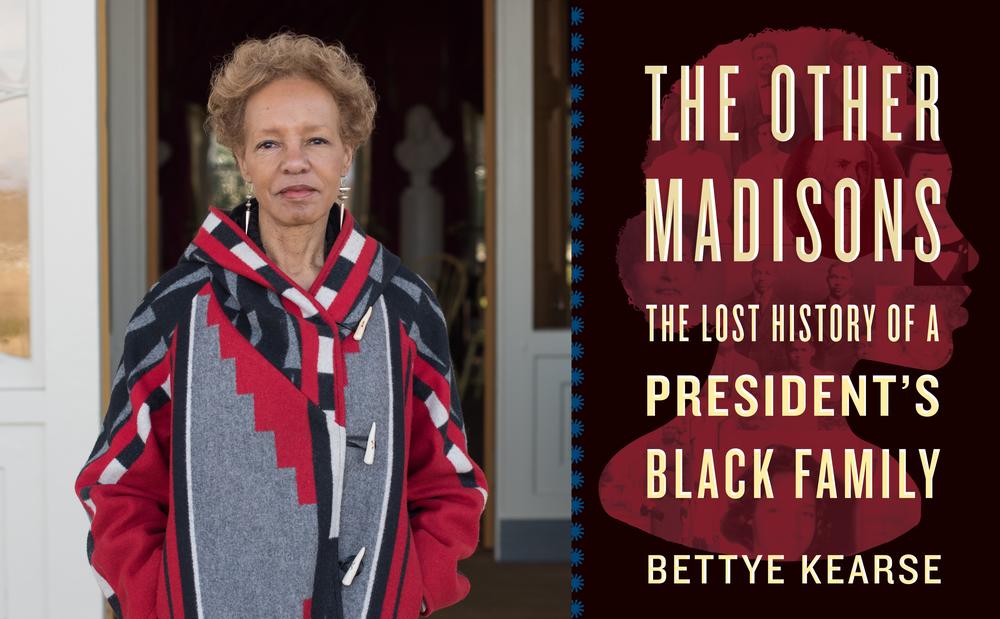

Author Dr. Bettye Kearse Challenges The Narrative Of Her Ancestry - Uncovering 'The Other Madisons'

Primary Content

James Madison was the fourth president of the United States, one of the founders of our country and author of the first drafts of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Dr. Bettye Kearse grew up being told that he was her great-great-great-great-grandfather.

“Always remember, you’re a Madison,” her mother often told her.

"On Second Thought" host Virginia Prescott speaks with Bettye Kearse.

Stories of that lineage were passed down through eight generations by family griots – or griottes in the feminine form – following a West African oral history tradition that goes back thousands of years.

Kearse is now a retired physician and geneticist, but she was still practicing when her mother handed her a box filled with family photos, letters and documents. This, in effect, designated her as the next griotte to carry their stories forward.

Her book, The Other Madisons: The Lost History of a President’s Black Family, follows a nearly 30-year quest, covering many miles and many obstacles to confirm her lineage.

On Second Thought host Virginia Prescott spoke with Kearse as part of the Atlanta History Center's virtual author talks. They spoke about how, while her mother had reverence for the Madison family, Kearse’s own journey involved challenging some of the more difficult parts of her history.

“She was very proud of being a descendant of President Madison, and I think in some way reassured — in some way comforted — by having something special in her family background that set her apart from those who were experiencing the really difficult parts of being black in America,” Kearse said. “I came along ready to punch it in the face.”

That includes raising the question of what it would mean for James Madison to have had a black family to begin with.

“I called her up and I said, ‘You know that President Madison and his fathers were rapists?’” Kearse said. “And she was quite uncomfortable with that term – and her term that she preferred was ‘visiting.’”

Kearse explained that tracing her lineage, and challenging the accepted narratives around it, helped her understand and appreciate her ancestry more deeply.

“I got an inkling, just an inkling of what my ancestors had gone through and how they helped, to their experience, shape me,” she said. “I learned a lot about their incredible strengths, their inner strengths, their sense of balance, their sense of hope. And, of course, the talents and values that they had, that they passed down to all of their descendants. This is true for every slave family, not just mine.”

This audio is an edited version of the conversation, but you can hear (and watch) the full interview here. The virtual author talks, which are free events, resume 7 p.m. Thursday, May 21 with Stephanie Danler.

For a full schedule and Zoom links, visit the Atlanta History Center’s website.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On the generational difference in embracing Kearse’s lineage

I'm a product of the '60s, so I came of age – or reached womanhood, let me put it that way – during the civil rights movement, the black power movement and, very importantly, the women's movement.

I felt licensed to sort of take on some of the more uncomfortable sides and really not try to hide them, you know, try to talk about them head on, which was very different from the way my mother looked at it. She was very proud of being a descendant of President Madison. I think in some way reassured, and in some way comforted by having something special in her family background that set her apart from those who were experiencing the really difficult parts of being black in America. I came along ready to punch it in the face.

On her mother’s hesitance to recognize injustice in her family

I was sitting on the floor of my bedroom with a bunch of papers around me when I happened to decide to call her, because I was thinking, "Does she really recognize what this was?" So, I called her up and I said, "You know, that President Madison and his fathers were rapists?" And she said, "Really?" and I said, "Yes! That's what they were." And she was quite uncomfortable with that term – and her term that she preferred was "visiting."

On challenging her family’s accepted narrative of their ancestry

I was the first to take up the bat. You know, not just my mother, but my grandfather, who actually passed down those stories to her, always used the term "visiting" and never explained to her what it meant. And when my mother would go to someone else like his sister, my aunt Laura, they were very uncomfortable with talking about what had actually happened in a straightforward way and just refused to talk about it and were angry if approached with those kinds of questions.

On those who would remove America’s history of slavery from records

They’re deniers. They’re, I guess in some ways, not unlike my Aunt Laura, who didn't want to talk about [...] this painful part of American history. You know, it happened. It's a very important part because this country wouldn’t have been what it is without the millions of slaves who did the work to make it what it is.

On the value of tracing her own lineage

They help me to understand who I am. I grew up in a very solid, middle class, very protected environment, so I didn't have any idea of what my enslaved ancestors had gone through.

I just felt like I was missing part of myself. So I would look for them. I looked for Mandy in all the places that you name. I looked for Coreen at Montpelier, and I literally walked in her footsteps, which was just a profound experience.

In so doing, I got an inkling, just an inkling, of what my ancestors had gone through and how they helped, through their experiences, shape me.

I learned a lot about their incredible strengths, their inner strengths, their sense of balance, their sense of hope. And, of course, the talents and values that they had, that they passed down to all of their descendants.

This is true for every slave family, not just mine.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457