Section Branding

Header Content

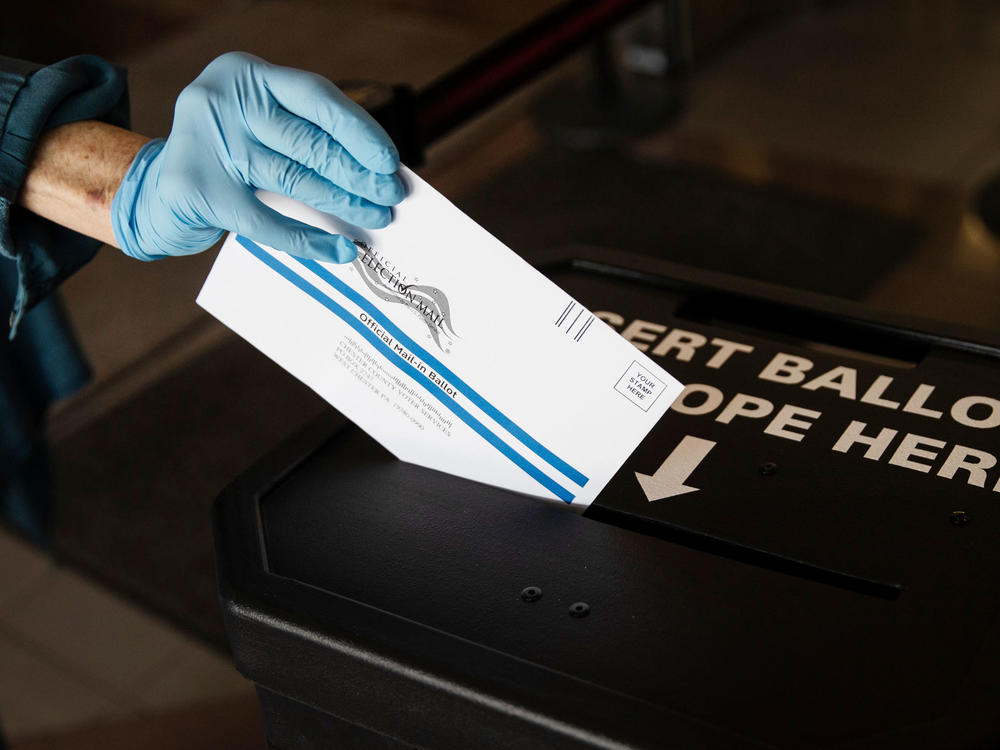

'Swing County, USA' Prepares For Unprecedented Influx Of Ballots By Mail

Primary Content

The county government cafeteria in Northampton County, Pa., is a large, airy room with big windows and, for now, lunch tables separated by plexiglass.

But a few months from now, on Election Day, this is where the county plans to have a couple of dozen people processing what it expects could be 100,000 mail-in ballots, nearly triple what they handled in the June 2 primary and 15 times what they handled in November 2016.

The dramatic rise in mail-in ballots prompted the move of the counting operation to the cafeteria, one of many steps this swing county on the eastern edge of a battleground state is taking to prepare for this unprecedented presidential election.

"We're very supportive of it. It's just a little more work," says Northampton County Executive Lamont McClure Jr. "Based on our experience from the primary, we just don't think it's physically possible to count the potential 100,000 mail-in ballots that day."

Pennsylvania is among the handful of states that could decide the outcome of the election if it's close. It voted twice for Barack Obama before pivoting to Donald Trump in 2016.

Like many other places across the U.S., officials are anticipating a tremendous increase in the number of people voting by mail, because of changes in laws and coronavirus concerns. While there's little evidence that mail-in ballots are insecure, they do introduce logistical and other challenges.

"Every component piece of the process requires more — more dollars, more space, more staffing, more equipment. And earlier timelines," says Secretary of the Commonwealth Kathy Boockvar.

Historically, only about 5% of Pennsylvanians voted absentee. That was already set to change this year, as Pennsylvania joined more than 30 other states in allowing voting by mail for any reason, also known as no-excuse absentee voting.

Gov. Tom Wolf hailed the new law, passed last fall, as "the biggest change to our elections in generations ... removing barriers to the voting booth and encouraging more people to vote."

Pennsylvania election officials say they expected a modest increase in mail-in voting in the 2020 primary, the first election under the new rules.

"And then COVID-19 hit," says Boockvar.

Statewide, Pennsylvania saw a nearly 18-fold increase in mail-in voting in the June 2 primary, compared with four years ago. Boockvar anticipates that 50% of the state's voters could opt for mail-in voting this fall.

The sheer numbers, along with the complexities of counting mail-in ballots, have raised questions and lowered expectations about how soon there will be results — not just in Pennsylvania but across the country.

For months, President Trump has promoted the false narrative that mail-in voting will lead to fraud and a rigged election. To be clear, though there have been issues as the use of mail-in voting increases — such as ballots rejected for being late or unsigned — election experts say there is no evidence that voting by mail leads to rampant fraud.

But because of how time-consuming the process is, a big question remains: On election night, will voters know who is going to be the next president of the United States?

It's the "million-dollar question," says Boockvar. "I think that Nov. 3, we may not."

Boockvar is hoping the Pennsylvania legislature will pass a measure that would allow ballots to be pre-canvassed, starting as early as three weeks before Nov. 3. That process includes opening both a ballot's outer envelope and secondary privacy envelope and confirming the voter's eligibility. Under current law, this work can't start until 7 a.m. on Election Day.

The final step, feeding the ballot into a scanner that counts the vote, would still happen on Election Day under the proposed legislation.

"That last part is the fastest part of the process," Boockvar says. "It's all the other things, including literally the physical extraction of the documents in the envelope, that take a remarkable number of hours and days depending on how many ballots you get back."

This spring, things actually ran pretty smoothly in Northampton County, where officials proudly point out that they were the first in Pennsylvania to report election results in the June 2 primary, at around 9 p.m.

Still, they say that without the ability to pre-canvass mail-in ballots ahead of Election Day in November, same-day results are unlikely.

"We'll have significant numbers on election night, but we won't be done unless the law changes," McClure, the county executive, says.

There is already a lot of interest in how Northampton County will vote come Nov. 3. The county, about 90 minutes from both Philadelphia and New York City, is looked to as a bellwether in presidential elections.

"If you go and look back historically all the way to the early part of the last century, you'd see that the way Northampton County goes, so does Pennsylvania," says Chris Borick, director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion, who lives in the borough of Nazareth, in the center of the county. "It's really unbelievable as a predictor for the state as a whole."

Northampton County was one of three Pennsylvania counties that voted twice for Barack Obama before pivoting to Donald Trump. Trump won Pennsylvania by a mere 44,000 votes, a margin of less than 1%.

"We like to call ourselves Swing County, USA," says Sam Chen, a Republican strategist and political science professor who grew up in the steel town of Bethlehem, Pa.

Chen, who did not vote for Trump in 2016, says he hasn't decided yet whom he'll support this year, though he's leaning toward former Vice President Joe Biden.

One thing Chen has decided is that he will vote by mail, and he's expecting a lot of other Republicans to do the same, despite Trump's attacks on mail-in voting.

"It's going to come down to convenience," Chen says. "Is it easier for me to vote in person?"

Others are more skeptical. Frank DeVito, an attorney and one of two Republicans on the Northampton County Election Commission, says Trump's rhetoric railing against mail-in voting is resonating with Republican voters. In recent weeks, for instance, Trump has claimed without evidence that millions of ballots could be printed by foreign countries.

"Is it possible what he's saying? I mean, yeah, in theory," says DeVito, speaking at his home in Bath, Pa., with a "Trump-Pence 2020" sign in his front yard. "Theoretically, when anybody who's a registered voter can mail a ballot in and never show up at a polling place, never sign in, it's more likely that you can commit fraud."

"On how wide of a scale is something like that going to happen?" DeVito continues. "It's likely that there will be a few paper ballots mailed to the wrong addresses and somebody will just use it. But on a systemic, widespread level, I really don't know. I think it's a real possibility."

There were already notable differences in how Republicans and Democrats chose to vote in Northampton County's June primary.

Among Democrats, 26,440 voted by mail, versus 10,051 who voted at the polls. Compare that with Republicans: 10,367 voted by mail, with 15,582 voting at the polls.

Northampton County Executive McClure, a Democrat, wants to get the word out that either form of voting is fine.

"It appears that Republicans prefer to vote in person, and we've got a great system for them, and they know their votes are going to count," McClure says. "And it appears Democrats prefer to vote by mail at this juncture."

As the county election staff members await word on whether they will be able to pre-canvass the mail-in ballots ahead of Election Day, they're already in better shape than they were for the primary. They have purchased a third high-speed envelope-opening machine, known as an enveloper, which can slice open 24,000 envelopes per hour.

McClure says he has great confidence in the technology, in the backup systems and in the people running them.

"I'd die before I let this election be rigged," he says. "There are some things that are greater in importance than a partisan victory: the sanctity and integrity of our elections."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.