Section Branding

Header Content

Americans, Go Home: Canadians Track U.S. Boaters Sneaking Across The Border

Primary Content

Canadians are typically seen as pretty friendly people, and until the coronavirus pandemic, most were happy to welcome Americans.

But when the coronavirus began to quickly spread in March, the U.S. and Canada shut their shared border to all nonessential traffic.

Since then, Canada's border patrol has effectively prevented caravans of Americans — and their RVs and their campers — from surging across the border as they normally do each summer.

But Americans can be crafty.

Some have managed to enter Canada by telling border patrol officers that they are on their way to Alaska. This is known as the "Alaska loophole."

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police fined several Americans who were hiking near Lake Louise in Alberta. Lake Louise is not on the way to Alaska.

Fed up, Canada announced last week that it is cracking down on Americans who apparently don't know which way is north.

The Americans are coming, the Americans are coming

Foreigners are also arriving by boat, often on sailboats and luxury yachts. Many seek refuge in British Columbia's protected inland waters and marine parks, which are home to pods of killer whales and abundant wildlife.

But the number of American pleasure craft arriving from Washington state has alarmed Canadians living just across the border.

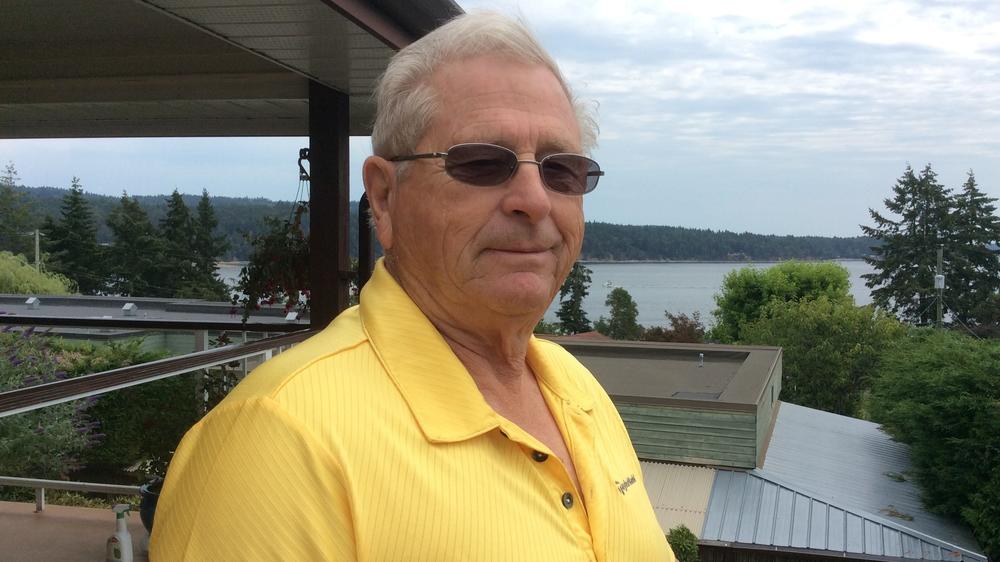

For George Creek, a former insurance agent, whose home overlooks Nanaimo Harbor in British Columbia, it has been a call to action.

"A number of us that are retired boaters and still members of the Council of BC Yacht Clubs started looking at the number of American boats that were crossing our border, in spite of the prohibition by the federal government," says Creek, president of BC Marine Parks Forever.

And they can do so from their living rooms.

Under international maritime law, every passenger ship must be equipped with an automatic identification system that is to remain on at all times. This allows for tracking ships in real time and helps prevent collisions in fog and bad weather.

Anyone with a computer and an Internet connection can click to see what kind of vessels are sailing, where they've recently been and which country they are from.

And plenty are from the United States.

Creek estimates that right now some 30 to 40 American pleasure boats are cruising through British Columbia's pristine waterways.

Lately, however, many have gone dark. Creek says that the Americans have figured out that they are being tracked through their transponders.

"They're turning them off as they cross the border," says Creek. "We see them on the computer, and at a particular point a few minutes later, they're not there anymore."

The maritime posse of retirees knows the boats didn't suddenly turn around, or sink. That's because Canadian boaters up and down the inland coast call and radio in the location of suspicious vessels, i.e., American boats. They report sightings to the RCMP's marine division, though it's unclear if any arrests have been made.

"The biggest petri dish in the world"

American yachts sneaking across the border makes Creek, and a lot of other Canadians, angry.

There is widespread alarm at how fast the coronavirus has spread through the Lower 48 and what many Canadians view as Americans' flagrant disregard for mask wearing and maintaining a safe social distance.

A poll conducted by Nanos Research found that eight in 10 Canadians want the border to remain closed to nonessential U.S. traffic because of fears of the coronavirus.

"When I called the U.S. the biggest petri dish in the world, that was not just off the cuff," says Creek.

Creek is particularly concerned about the tiny isolated communities, such as Refuge Cove on Desolation Sound, where boaters stop for fuel and food. Many are home to First Nations people and have no medical facilities.

Canadian boaters recently got riled up after a large yacht from the U.S. stopped at one of the small outposts for supplies.

"They wandered the dock," says Creek bitterly. "Three or four adults and the rest were teenagers with no social distancing, no masks, and went through the store as if they were just shopping at Walmart."

To boaters sneaking into Canada to enjoy its marine parks and secluded coves, George Creek wants you to know: You are being watched.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.