Section Branding

Header Content

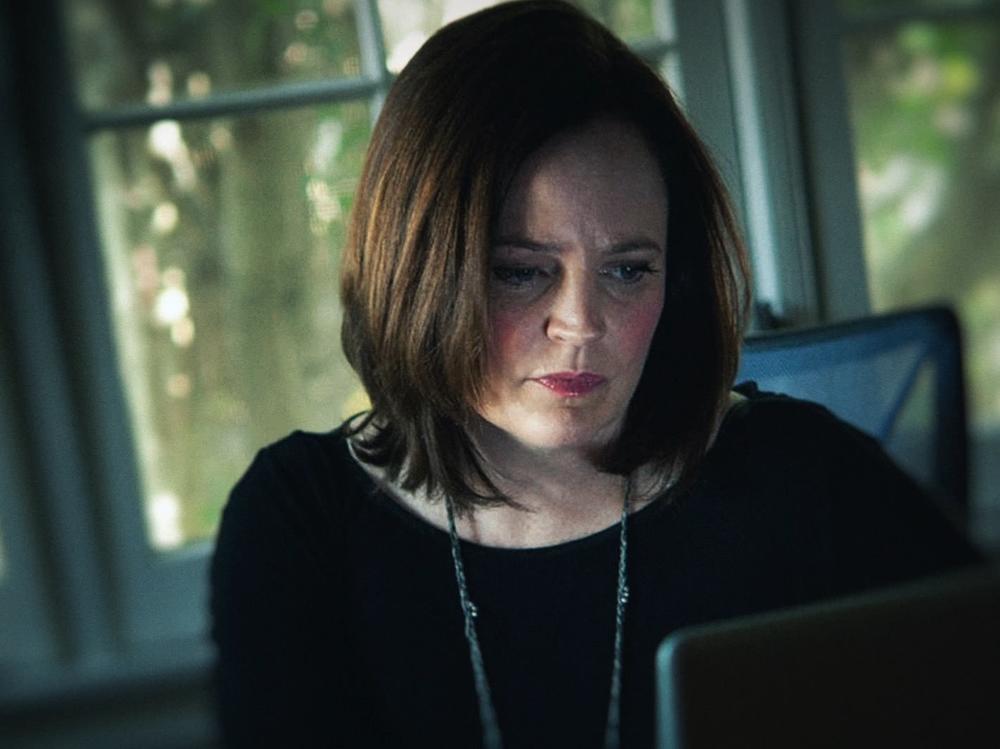

'I'll Be Gone In The Dark' Sheds Light On Both Justice And Its Pursuers

Primary Content

The HBO documentary series I'll Be Gone In The Dark, which concluded Sunday night and is now available on demand in its entirety, is based on crime writer Michelle McNamara's book about the case known as "The Golden State Killer," who was believed to be responsible for multiple rapes and murders during the 1970s and 1980s. But ultimately, the series is more about McNamara herself than it is about the case — and it's more interesting for it.

There are two things a lot of people who haven't read her book may know about Michelle McNamara other than her writing and specifically her pursuit of this case: she was married to Patton Oswalt, and she died in April of 2016, two years before the criminal she spent a good chunk of her life chasing was apprehended. The former police officer who was ultimately arrested — and who pleaded guilty to 13 murders — wasn't any of the people she had suspected. He was found using DNA evidence not directly related to her work. Commentators have, ever since, struggled to balance their respect for her tenacity in keeping the case active in the mind of the public with concerns about how her obsession with it seems to have eaten away at her, and maybe even contributed to the accidental overdose that caused her death.

These are not easy things to talk about. They are not easy to talk about with regard to anyone, let alone someone whose widower has walked a public and candid path of managing grief as a suddenly single father of a young daughter. (I attended Oswalt's first performance after she died, at the Beacon Theater in New York, and I can attest to the fact that it was a raw and remarkable piece of work.) And for most of its run, it appears that I'll Be Gone In The Dark will tread lightly on the darker elements of McNamara's story, concentrating mostly on the investigation itself and the work she was doing, mentioning but not really dwelling on the healthy or unhealthy nature of "amateur detective" work that can easily become obsessive.

In the final two installments, though, series turns a sharper eye toward true crime as an obsession and a genre. Crime stories have a way of lionizing the dogged detective, the person — whether a curious observer, someone in law enforcement, or a family member — who will not give up. Time and time again, we have seen people tippy-tapping away on keyboards, finding clues, uncovering what no one else could. They get what is defined, sometimes quite imperfectly, as justice.

That's what Michelle McNamara spent years trying to do. But what the last two episodes of the series reckon with is that particularly for someone who has tendencies toward addiction and depression, this kind of figurative rabbit hole can be the setting for a true descent, a disappearance into darkness that becomes enormously hard to halt. Oswalt talks movingly about his regret in not realizing how serious her dependence on pills was becoming as she talked about what she was taking to get going in the morning, to get to sleep at night, to stay calm, to stay focused on the book she was writing. And as easy as it might be to stand in judgment of the missed moment in which he might have intervened — he clearly agonizes over it himself — she was clearly a highly functional and highly regarded person. His decision to assume she knew what she was doing is one I suspect a lot of us might make.

It makes sense, of course, that to immerse yourself in a story of violence — in this case, many, many stories of violence involving many victims — can be suffocating. These are the darkest parts of human experience; how can poaching in those images and memories day after day, without even the structure a lot of professional settings might impose, not change you? Even if the memories aren't yours and the images come to you through others' accounts, who's to say they don't affect you like secondhand smoke?

But the useful lessons here go beyond true crime and more generally to internet "research." For McNamara herself, those are unnecessary quotation marks — she knew what she was doing, she knew how to find reliable versus unreliable sources, and she knew how to check her facts before she acted. While her connection to the case may have been personally devastating, it was professionally responsible. But if you extrapolate from the ability of this case to suck Michelle McNamara down a well until she could do little except search and search and search, trying to complete her book, you begin to better understand the risks of some of the misinformation we confront now.

Where McNamara found a community of obsessives who wanted to talk about nothing but the Golden State Killer, others find communities of obsessives who want to talk about nothing but medical and political disinformation. And again, for people who are given to addiction and depression, it's easy to imagine the focus of life growing narrower and narrower. In her case, her cause was just and her thinking was relatively clear. But there's no reason to necessarily assume that it's only in those cases that the ability of a research hobby, fed by essentially unlimited information of undifferentiated quality, can overwhelm people. Here is a woman who knew what she was doing, who was surrounded by a loving family. Imagine what would happen to people who didn't, and weren't.

And, too, imagine these same end questions she was pursuing — guilt, judgment, justice, declarations of truth — in the hands of people more eager to demonstrate some measure of success in their seeking. Imagine McNamara's single-mindedness without her restraint. Imagine the pressure to satisfy and impress a community of like-minded people without the accompanying knowledge that to speak recklessly is dangerous.

As a true-crime series about the Golden State Killer, I'll Be Gone In The Dark doesn't add much to what we already knew — what McNamara told us herself in her book, completed after her death by some of her associates. Where it adds the most to the story is in the things she did not explain, precisely because they were happening to her, and not to the people whose stories she wanted so badly to tell.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.