Section Branding

Header Content

'It Lowers Your Blood Pressure': Spend A Few Moments With These Hypnotic Trees

Primary Content

I'm a New Yorker. Trees in Manhattan grow with little metal fences around their bottoms. So I didn't learn about lying under trees until I had a backyard in Washington, D.C. That delay surely stunted my growth. But this tree, at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Neb., has recuperative powers for anything that ails you.

Click the video below and watch what happens when the tree moves. (Just watch. Turn off the sound. I'll tell you what the curator says after you ... just ... look.)

It's a digital animation. The tree moves and changes color with the seasons. "It's a very subtle way of making you realize that time has passed," says Joslyn curator Karin Campbell. You don't catch the seasonal shift the first time you see it. So you want to watch it several times. (Feel free to click again. The changes are hypnotically subtle.) "Makes you want to keep coming back."

Video artist Jennifer Steinkamp created the tree above entirely on her computer. In doing so, curator Campbell says, "this goes between video and painting and drawing for me. It bridges the different media."

Think how many trees there are in art. Loads, even though they're hard to paint. But artists are drawn to them. Maybe because they stand for shelter, safety (except in electrical storms), the promise of inevitable renewal — hope. Or just because they're beautiful. In 1929, Georgia O'Keeffe painted "The Lawrence Tree," a big ponderosa pine on British writer D.H. Lawrence's ranch in Taos, N.M.

O'Keeffe lay on her back under the tree, to get that perspective. She wanted it to hang as if the tree were standing on its head. But her picture sometimes gets hung upside down. Doesn't really matter, it's so good. I had an art teacher at the High School of Music and Art who said we should keep turning our paintings upside down and sideways, to see if they held up.

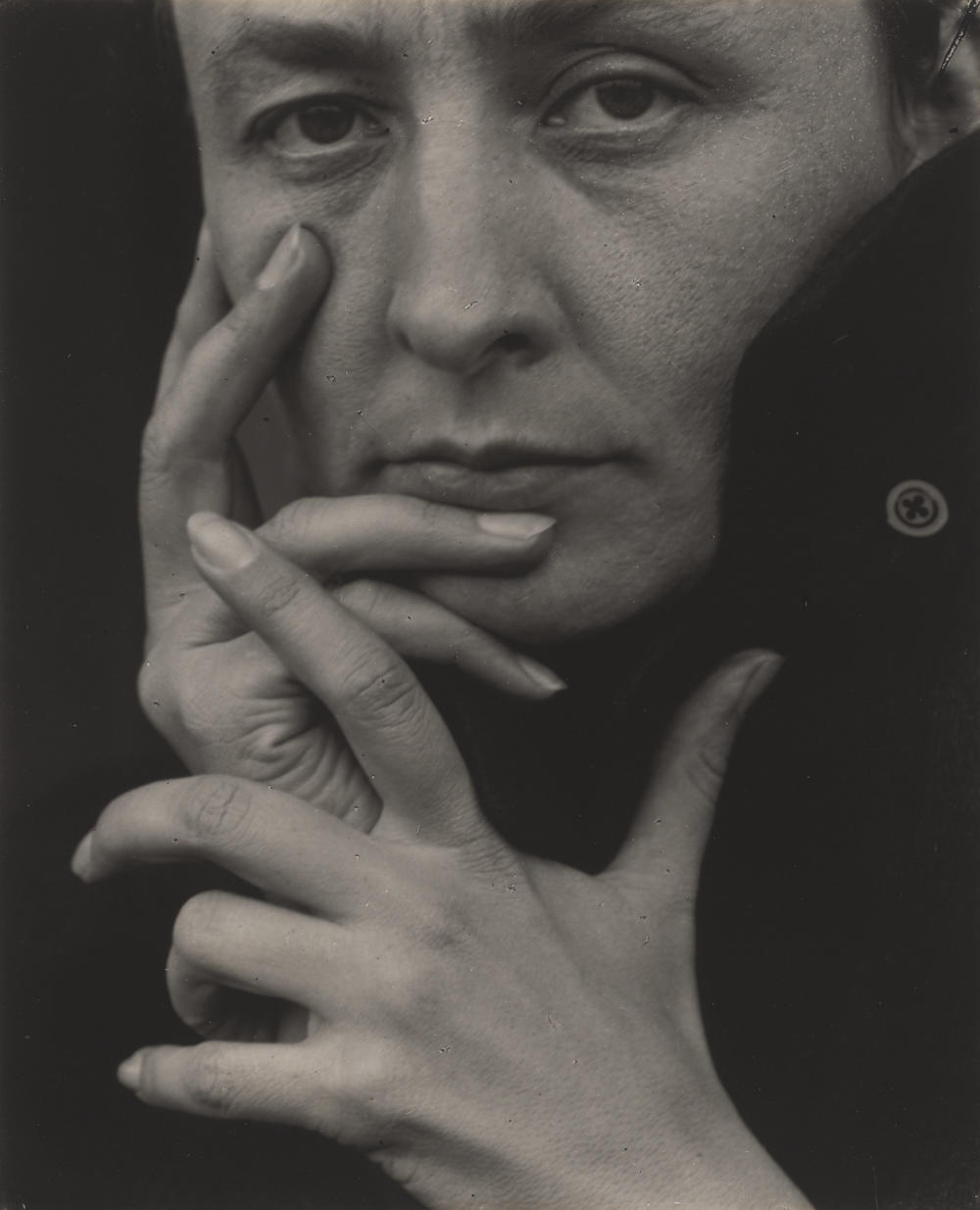

Like the Joslyn animated tree, O'Keefe's tree has no roots. But look at the swirl of branches she's painted. They could be wildly snaking roots. They remind me of O'Keefe's hands. They're wild and gorgeous in this photo her lover-then-husband Alfred Stieglitz took of her. Sinuous. She said she was always complimented on them, growing up.

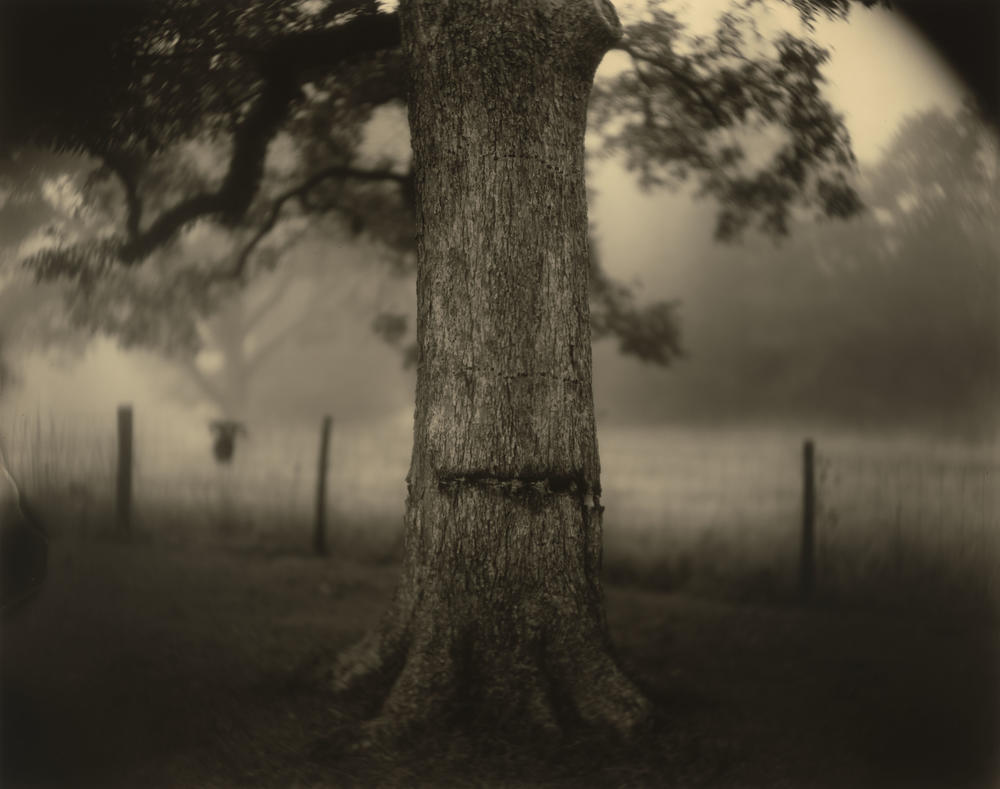

Just one more tree photo before we get back to the moving, swaying digital projection in Omaha. Sally Mann made Deep South, Untitled (Scarred Tree), in 1998.

"Sally has often spoken about the landscape as being a vessel for memory," says National Gallery of Art Senior Curator of Photographs and Mann expert Sarah Greenough. "She photographed Civil War battlefields to see, as she wrote, 'If the land remembered the horrific events that took place on it.' "

The gash on the trunk on this tree has healed, but remains visible. "She is portraying it," Greenough continues, "as a 'silent witness' to another age."

Our age, right now, can find solace in Jennifer Steinkamp's hypnotic, constantly moving tree in Omaha. Steinkamp calls herself an installation artist. She created all the images, and set them to motion in her computer. She's done a series of such trees — in honor of teachers who've had a profound influence on her. The one at the Joslyn is called "Judy Crook, 2." (There are 14 different Judy Crook tree animations. "I may make a couple more, " Steinkamp says. "They are fun to make, a lot of pruning.")

Steinkamp studied with Judy Crook at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena. Crook is a color theorist. If you ever took an art class you know about color theory (and like me, probably forgot it). Primary colors, secondary colors, what goes with what, what makes the eye happy. Steinkamp plays with lots of color shifts in her various Judy Crooks.

The teacher who set Steinkamp on the path to trees was someone she had in first grade in Edina, Minn. "Miss Znerold," says curator Karin Campbell, "who had the children make sponge trees."

Ever do it? Take a sponge, dunk it into paint, press it onto paper. Poof! Tree leaves. Pick another color. Poof! Blossoms. "At the end, Miss Znerold said Jennifer made the best tree." Years later, trees become her favorite theme. And of course, an early tree was in honor of that inspirational teacher.

These days, Steinkamp's trees pop up at museums and in private collections all over the world. But the first one I fell in love with is at the really stunning Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha.

Joslyn curator Karin Campbell says one board member's granddaughter calls Judy Crook 2 "The Magic Tree," and insists on coming to see it once a week. Campbell makes a pilgrimage, too. Especially in times of stress. "We made a joke when we first thought about the work, that we would put big beanbags down, and make it a hangout spot. ... It lowers your blood pressure, I find."

And, dear reader, you can do the very same thing for your blood pressure right now, in the comfort of your own home:

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing lively online offerings from museums while their buildings are closed due to COVID-19.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.