Section Branding

Header Content

Case Involving Officers Who Tased Mentally Ill Man To Death Goes To Georgia Supreme Court

Primary Content

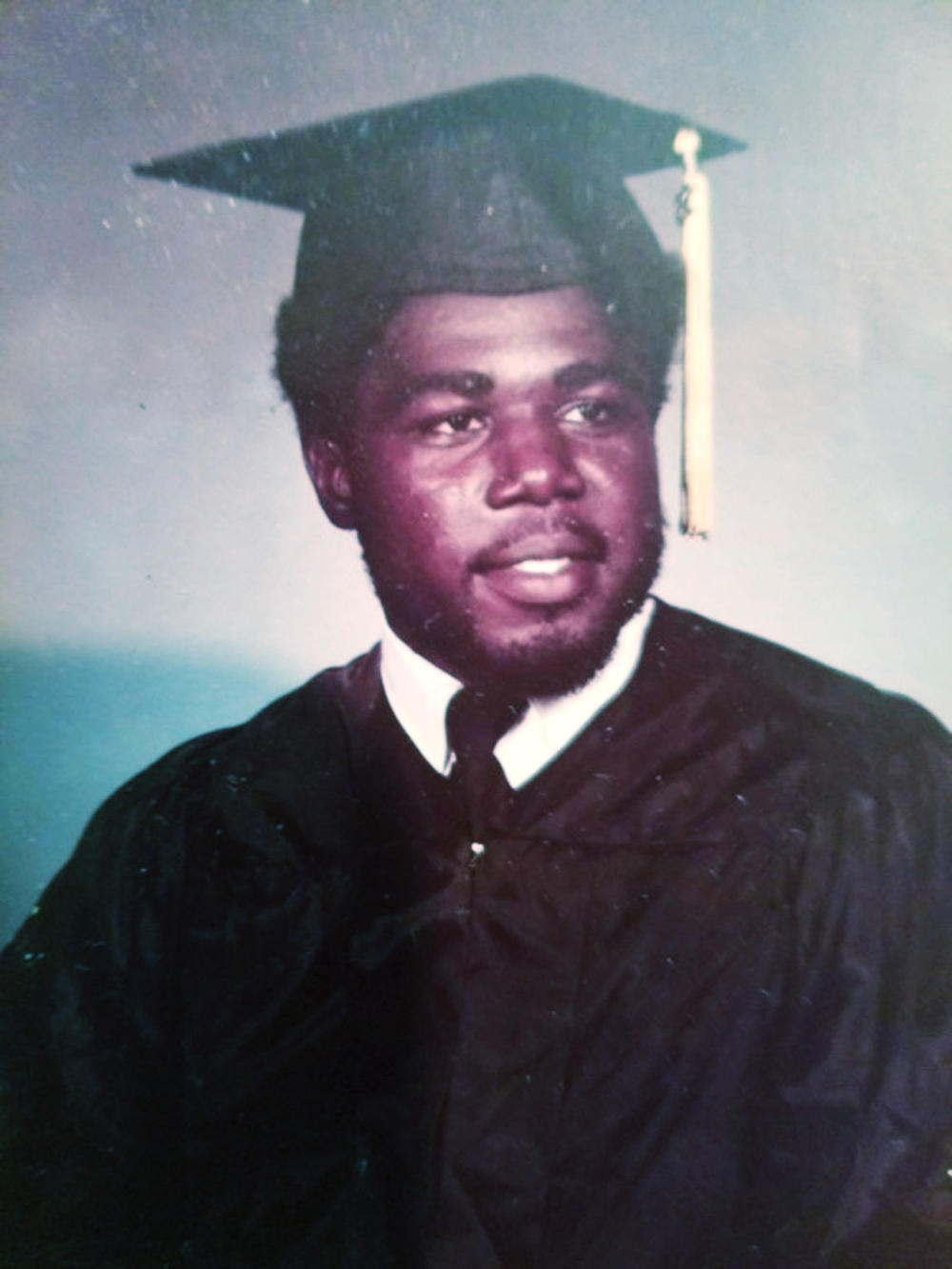

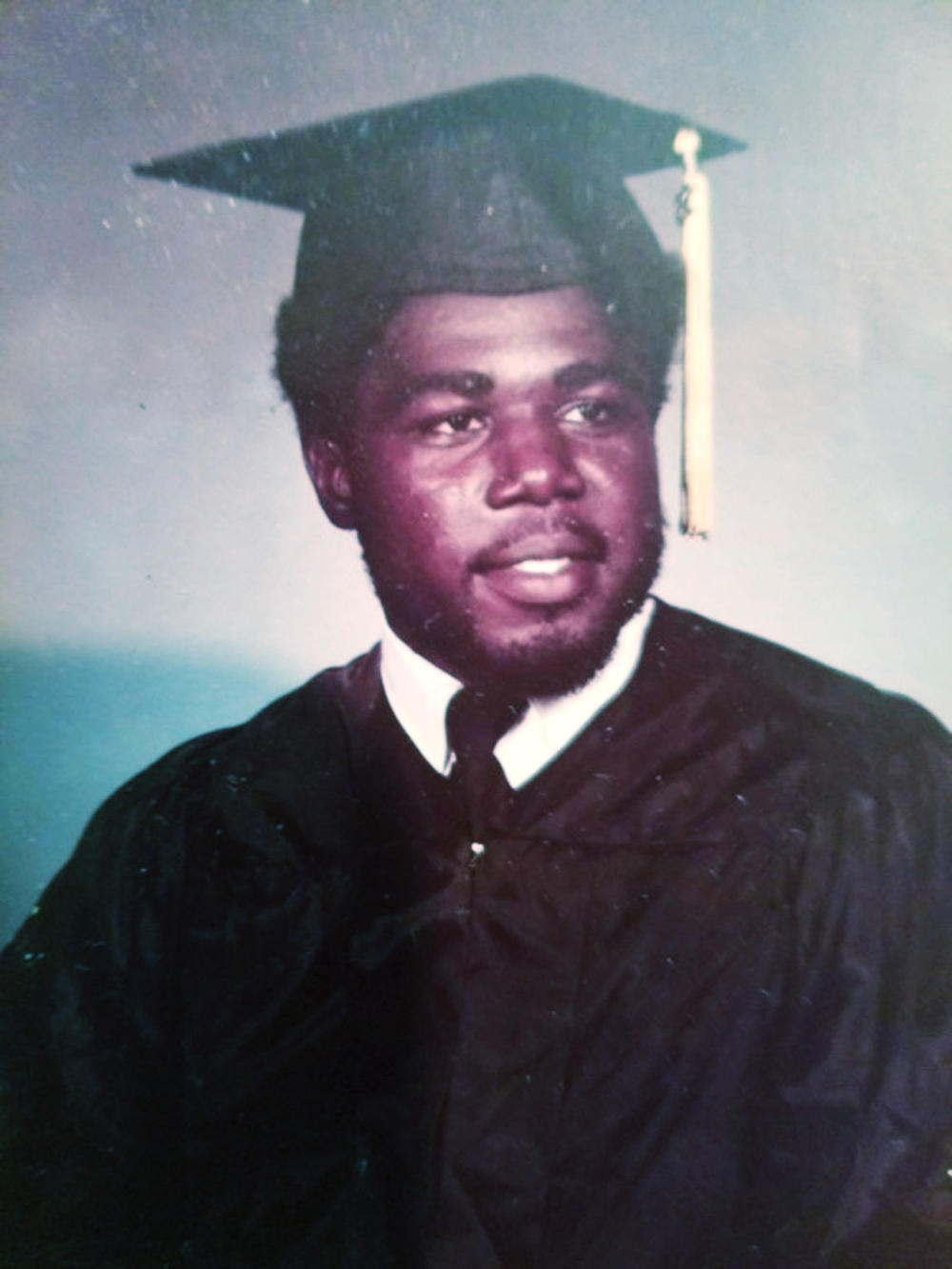

A case before the Georgia Supreme Court this month could have important implications for how police officers are held accountable when they kill while on the job. The question here is how Georgia’s stand your ground law applies to law enforcement. GPB’s Grant Blankenship has more about the death of Eurie Martin.

On a blisteringly hot day in July 2017, Helen Gilbert called 911 in Washington County, halfway between Macon and Augusta. She was worried about her brother, Eurie Martin.

“I’m concerned about him being out in all that weather,” Gilbert told a 911 dispatcher. She sounds near tears.

“Now where he’s going to, I have no clue,” Gilbert said.

It turns out Martin was on a 30-mile walk from Milledgeville to Sandersville.

Gilbert told the dispatcher Martin had a history of mental illness and was well past 50 years old. She wanted someone to find him and help him.

But unbeknownst to Gilbert, she called too late. Several minutes earlier, someone else had already called the authorities about Martin, and that call had led to his death.

Case Tests Law Enforcement Use Of 'Stand Your Ground'

The legal path following Martin’s death has led to a hearing before the Georgia Supreme Court, a hearing that could have important implications for how police officers are held accountable when they kill while on the job. At issue is how Georgia’s stand your ground law applies to law enforcement.

Martin’s thirst in the over 90 degree heat had caused him to stop on the outskirts of the town of Deepstep, which bills itself as “The Heart of Kaolin” at the city limits in honor of the clay mining industry that sustains a handful of east Georgia communities.

There, Cyrus Harris was cutting grass in front of his home, across the road from a chalk white and red kaolin pit, when Martin asked to fill the Coke can he’d cut in half to use as a cup with water from Harris’ spigot.

“He just walked right up in my yard. I don’t see no car, I don’t see nothin’,” Harris told a 911 dispatcher.

“I told him to get out,” Harris said.

Harris knew nothing about Martin's history of mental illness. All he knew, he said, was that he was afraid for his wife's safety -- and that the thirsty Black man in his yard was "filthy." Because of that call, when Washington County sheriff deputies arrived, they were looking for a suspicious person. They apparently had no knowledge of Martin's mental illness, either.

The 911 calls of Gilbert and Harris, dashcam video plus cell phone video made by passersby were presented as evidence against Washington County sheriff deputies Henry Copeland, Michael Howell and Rhett Scott who would eventually face murder charges in Martin’s death.

The video shows that once the deputies found Martin just inside the city limits of Deepstep, he ignored them until one of them deployed a Taser to slow him down. He tore the electrical contacts from his body and walked on. Up the road he was surrounded by all three deputies and tased again until he was handcuffed.

This time Martin did not get up.

Dashboard video taken soon after shows Martin face down in the grass, his hands cuffed behind his back, motionless. Martin had been tased for over a minute and a half total.

“We had to tase some ... He’s a Black male,” Deputy Copeland told a superior over the radio.

“We don’t know his name yet. He was acting crazy.”

It was five minutes after Copeland called his superior before anyone realized Martin wasn’t breathing, another four minutes or so after that before CPR was administered by an EMT.

Martin died in the grass on the side of Deepstep Road. In Washington County, parallels were drawn to Martin’s death and the killing of other Black men by police, like Eric Garner who died face down on a New York City street.

In Martin’s case, though, murder charges were brought immediately. The deputies were also fired shortly after the killing for violating several department procedures.

The first indictment was tossed on a technicality. In the second, the defense argued in a pretrial hearing the deputies should be immune from prosecution. In late 2019, a Superior Court judge granted that immunity.

“This immunity that they're talking about here is immunity from criminal prosecution based on the fact that you were justifiably acting in self-defense,” said Jim Fleissner, professor at Mercer University School of Law and an expert in the 4th Amendment.

“It's not unlike the law in Florida that they call the 'Stand Your Ground' law,” Fleissner said.

Fleissner said over the last 20 or so years, officers asking for immunity under stand your ground laws has become a kind of trend. Stand your ground laws allow the use of deadly force without an individual needing to retreat from the situation. It was under Florida’s stand your ground law that George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin.

Prosecutor: You Can't Be The Aggressor And Claim Stand Your Ground

Heyward Altman is the Middle Georgia Judicial District Attorney who presented the case against the deputies who tased Martin to death to both grand juries. He will challenge the immunity ruling in the Georgia Supreme Court.

Altman said a stand your ground defense ultimately rests on who started the fight.

“You cannot be the initial aggressor,” Altman said. “If you bring the fight to somebody, you can't later complain that person fought back.”

In his ruling, Judge H. Gibbs Flanders Jr. notes Martin never "displayed overt aggression," even though he was clearly “agitated and tense.” However, Flanders said under Georgia’s stand your ground law, and because of Martin’s non-compliance with officers’ who suspected him of the misdemeanors of loitering and walking in a public roadway, the use of force was justified.

Altman said because the deputies initiated the violence, the ruling could carve out special protections for law enforcement under stand your ground.

“What we’re saying is the court expanded that to include an officer and his use of force in making an arrest,” Altman said. “It expands the statute beyond what it was originally intended to be.”

Civil rights activist and attorney Francys Johnson represents Martin’s family. He said Georgia has a lot riding on the immunity appeal.

“We stand to gain everything when it comes to whether the value of a Black life is truly respected in the law and in Georgia,” Johnson said.

Already Martin’s death has changed the way the Georgia law officers are trained to use Tasers. Johnson said he hopes the case leads to bigger changes in how police are trained.

“Train them to preserve life,” he said.

In addition to the Georgia Supreme Court hearing on immunity for the three former deputies, some state legislators have begun considering changes to Georgia’s stand your ground law, especially in wake of the Ahmaud Arbery killing earlier this year near Brunswick.