Section Branding

Header Content

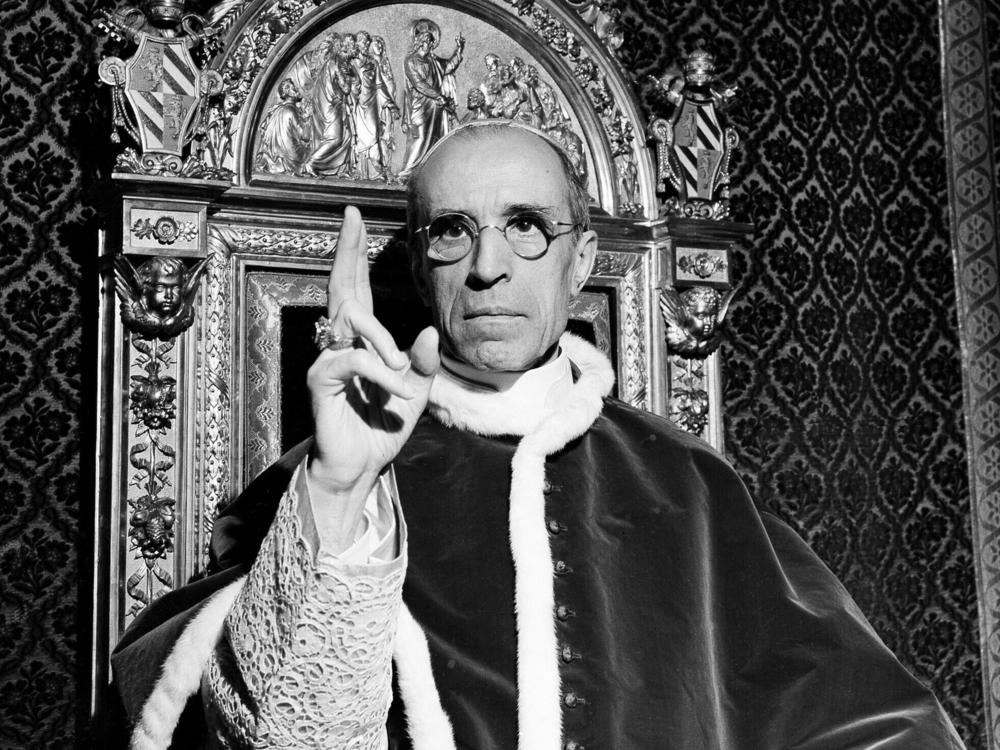

Records From Once-Secret Archive Offer New Clues Into Vatican Response To Holocaust

Primary Content

Vatican officials have always insisted Pope Pius XII did everything possible to save Jewish lives during World War II. But many scholars accuse him of complicit silence while some 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust.

"Pope Pius XII thought that he should not take sides in the war," says Brown University professor David Kertzer, "and that therefore he should not be criticizing either side of the war, including the Nazis."

Kertzer has written extensively about popes and the Jews. He won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for his book The Pope and Mussolini, which traced the rise of fascism in Europe. And he was among the first to have access to the Pius XII archives when the Vatican opened them in March, after decades of requests from scholars.

Kertzer has just published his early findings in an article for The Atlantic. The newly unearthed documents — some imbued with anti-Semitic language — are shedding light on the pontiff's behavior during the Nazis' massacre of Jews. They also reveal the pope's role in preventing orphans of Holocaust victims from being reunited with their relatives.

The historian found two documents that reveal an intense debate was under way in the Vatican in 1943, when the Nazi occupiers of Rome rounded up more than 1,000 Jews and detained them in a military college 800 yards from St. Peter's Square before packing them off to the Auschwitz concentration camp. As the German ambassador to the Vatican reported to Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, the roundup occurred under the pope's "very windows." Only 16 of the deportees survived.

The first document newly found by Kertzer is a letter written by the pope's longtime Jesuit emissary to Italy's Fascist regime, the Rev. Pietro Tacchi Venturi, who urged the pope to make a private, oral protest to the German ambassador. He suggested Pius tell the ambassador that there is no reason to use violence against Italian Jews because the racial laws instituted five years earlier by Benito Mussolini's dictatorial regime were "sufficient to contain the tiny Jewish minority within its proper limits."

Pius asked for further advice from his expert on Jewish affairs, Monsignor Angelo Dell'Acqua.

"The second document that I found," Kertzer tells NPR, "is Dell'Acqua's thoroughly anti-Semitic document explaining why he thought the pope should not, in fact, speak out."

The prelate thought it would be too embarrassing to protest anti-Semitic measures when, over many centuries, ruling popes had confined Jews to ghettos and had forbidden them from practicing professions.

And, says Kertzer, Dell'Acqua thought the emissary's letter was overly sympathetic to the Jews.

"He said Jews have caused problems ... do threaten a healthy Christian society. So why should the Church be speaking out for them when he says they haven't protested against the Nazis killing Christians?"

Pius never spoke out against Nazis killing Christians, Kertzer suggests, because he didn't want to offend many German Catholics who were ardent Nazis.

And so, again, Pius said nothing.

Dell'Acqua later became cardinal vicar of Rome.

Questions about Pius' wartime role began to grow more widely starting in 1963 in response to allegations raised by the German playwright Rolf Hochhuth in his play The Deputy. And still vivid memories in Rome of Pius' behavior during the Nazi occupation of Rome have stymied efforts to beatify him.

The Finaly brothers

Kertzer's findings also cover the case of two Jewish orphans secretly baptized in France after their parents were deported to Auschwitz.

The case of the Finaly brothers, Robert and Gérald, was the most serious case affecting French Jews since the Dreyfus affair —in which a Jewish French Army captain was wrongly convicted of treason — a half-century earlier. It dragged on for years and became a cause celebre. Nuns, monks and a mother superior were put in jail for kidnapping when they defied court rulings to hand over the boys to their surviving relatives.

French Church officials invoked a centuries-old doctrine claiming the baptized boys were now Catholics and must not be raised by Jews. In 1953, when media coverage of the affair was turning against the Church, the archbishop of Lyon asked the pope for guidance.

"This is when the Vatican began its involvement behind the scenes, because as it continued over the next months to issue instructions on how the Church should proceed, the Vatican is telling them to resist the law," says Kertzer. "They also specified to be sure that no one knows that these orders are coming from the Vatican or from the pope."

In 1945, the Finaly brothers were two of the estimated 1,200 French Jewish orphans in France alone in non-Jewish families or institutions. Across Europe, Kertzer believes, there were thousands more — secretly baptized and never reunited with their Jewish relatives. He writes in his Atlantic article that on Sept. 21, 1945, the secretary-general of the World Jewish Congress, Léon Kubowitzki, went to the Vatican to appeal for help in locating Jewish orphans. Pius replied, "We will give it all our attention."

Ultimately, the Finaly boys were reunited with their relatives in Israel where they now live in retirement. Following his discoveries in the archives, Kertzer contacted Robert Finaly, who described to him what it was like when he and Gérald were being shuffled around in hiding in various convents.

"They were made to fear Jews," Kertzer says. "They weren't told that their family was trying to reclaim them. And they were taught that Jews were damned by God and would live in eternal torment in hell when they died. They were scared stiff of Jews, of being Jewish."

The Vatican's mindest

The historian says his findings help fill many of the behind-the-scenes gaps at the Vatican during the war and its aftermath. But there is one question, says Kertzer, Pope Pius XII never seemed to ask:

"How could so many thousands and hundreds of thousands, if not millions of Germans and their allies take part in the mass murder of Jewish children and old people and so forth, still thinking they were good Catholics?"

Kertzer says his findings reveal that the horrors of the Holocaust did not temper the Vatican's anti-Semitic mindset.

That mindset was not repudiated until 20 years after the war when, with the Second Vatican Council, the Roman Catholic Church formally rejected the centuries-old Catholic doctrine that held Jews responsible for the death of Christ. That ushered in a new era of Catholic-Jewish dialogue — and ultimately the opening of the Pius XII archives.

And, Kertzer says there's still much more to be learned from the newly available trove of documents.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.