Section Branding

Header Content

Boston's Museum Of Fine Arts Turns 150, Celebrates Monet's 'Lasting Impression'

Primary Content

I begged her. But Ann Hoenigswald was resolute. The National Gallery of Art's Senior Conservator of Paintings (now retired) is a dedicated museum professional. Also she knew I'd blab it to everyone. So, firmly and very sweetly, she smiled and said, "No."

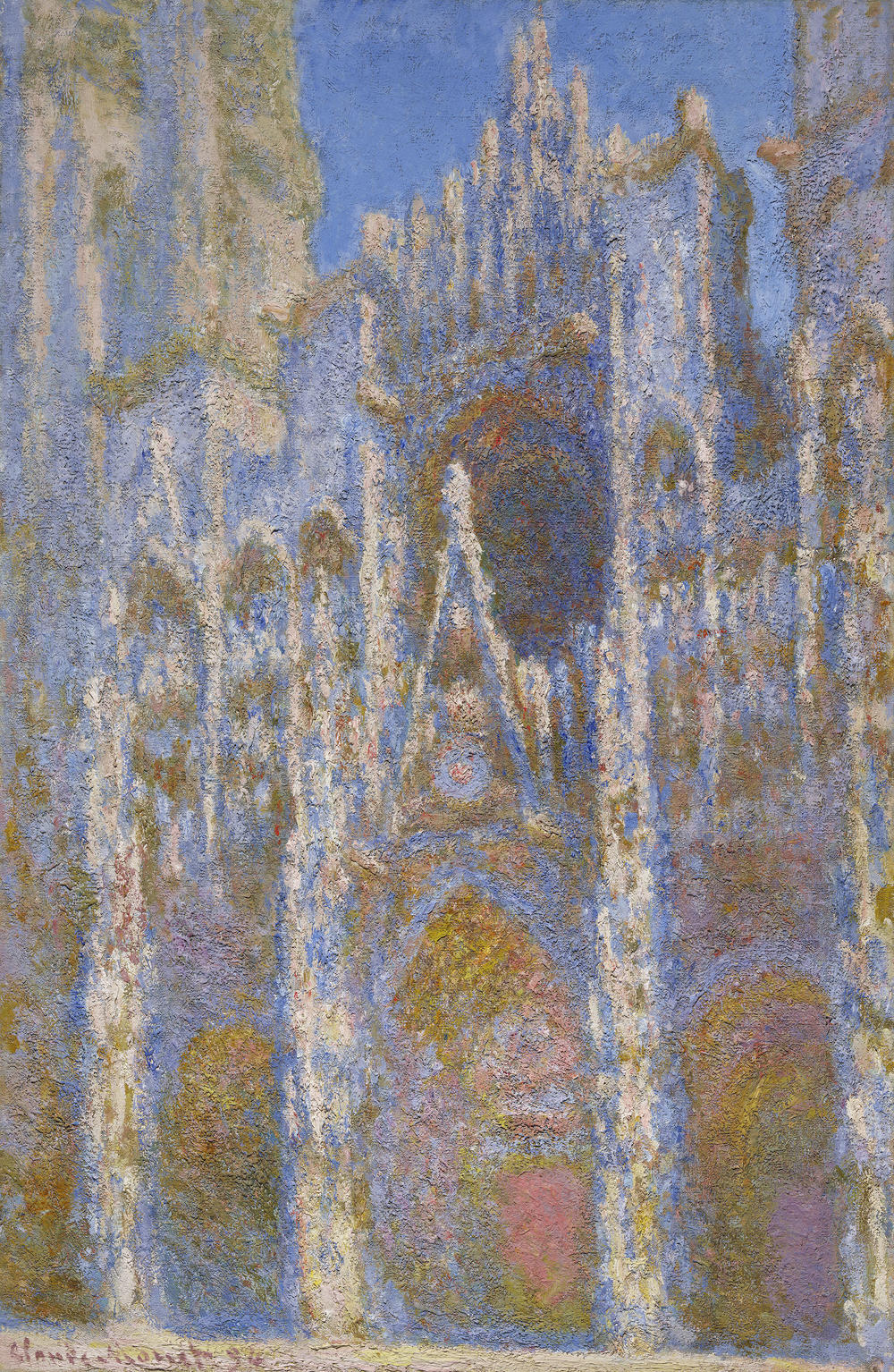

We were in the NGA conservation lab — a fascinating place I love to visit. That day years ago, on her easel, was Claude Monet's Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight. Unframed, just sitting on the easel as if the Impressionist master had left maybe an hour earlier, parking his palette and brushes on the table. But it was Ann's palette. She was doing conservation work on the canvas — filling in tiny spots where Monet's bright blue had disappeared.

It didn't look that hard. Dip a brush into the sky blue paint she'd perfectly matched to Monet's, scoop up a tiny dab, and dot it onto the painting. I would have been sooooo careful. And euphoric. But no. Of course Ann was right. I would have blabbed. And violated her contract with her profession.

Monet painted the Rouen Cathedral 20 or more times. Here's one he did the same year as the one up top.

This one belongs to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The museum is closed (hoping to re-open in the fall), but it's celebrating its 150th anniversary online with this and other works, in the exhibition "Monet and Boston: Lasting Impression." Thanks mostly to Boston collectors, the MFA owns 35 Monets — they say it's one of the largest collections outside France. You can see some of them for yourself here.

The MFA has lots to offer on their website — you can hear a violinist play pieces composed during Monet's lifetime (1840-1926). Or download one of his paintings to use as background for your next Zoom meeting (really must try that one).

MFA curator Katie Hanson says Monet's Rouen series captured the glorious Gothic cathedral at different seasons and times of day, exploring how light and weather changed it. With this persistently varied repetition, Hanson thinks Monet forces us to "slow down, look and feel more carefully, and focus in a sustained way on what we see, and how we see it." He makes us realize how the world keeps changing.

Monet did several series: Grainstacks, waterlilies. I was thrilled to find a film of him painting near his lily pond in Giverny. It's from 1915, when he was 75 years old.

See how quickly he worked? I know, I know. Old film moves fast. And I'm sure he was smoking a Gauloise. But I digress.

The canvases look so luminous to us. Cheerful. Happy. (On social media, a visitor to the MFA website wrote they're "breaths of peace in a Van Gogh life.") That cheer took a lot out of the artist. Katie Hanson says while he was working on the grainstacks he "writes of his rage at how difficult it is to get what he experiences onto the canvas." Not easy to show mist, or shadow, or dusk.

By the time he painted the various series, Monet was decades into Impressionism — the style of quick strokes and airy atmospheres he and Pierre-Auguste Renoir launched in the late 1860s. Hanson told a story I'd never heard, about how the two pals were painting outdoors one day, making small quick canvases they intended to take back to finish — smooth them out, do some polishing.

Done for that day, Hanson says, "they bring them home to the studio and they kind of look at them and think, 'This could stand on its own.' " They realized those first impressions were good — fresh, new — different from the traditional, finished works that ended up in the Salons, the official and highly influential, juried and judgmental annual Paris exhibitions where contemporary artists showed their wares, got reviewed, and maybe got bought.

Well, the Salons kept rejecting their first impressions, so young Monet, Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot and a few other fresh thinkers put on their own exhibition. In 1874 a critic looked at Monet's Impression, Sunrise and said witheringly, "Right. It is an impression. And you all are a bunch of Impressionists." Or the French equivalent.

Took a lot of moxie for these 30-something revolutionaries to show their "unfinished" works. They lived off their paintings after all. "These are artists who are struggling to pay their rent," Hanson says. But they were determined to share their new vision. Persistence paid off, eventually. By the 1890s Monet was a rich man.

He was living in Normandy — the town of Giverny — by then, in a gorgeous house, and a lily pond he'd put into the fabulous garden he planted. Painting the lilies and the pond, his canvases grew more and more abstract. He left out horizon lines and skies. He got closer and closer to the surface of the water.

Monet was at the height of his fame. He didn't have to innovate, but couldn't not innovate. About this work, a critic said: "No more Earth, no more sky, no limits now." Only unlimited pleasure.

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing lively online offerings from museums while their buildings are closed due to COVID-19.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.