Section Branding

Header Content

2020 Is The Year Of The Woman Donor: Campaign Contributions Surge

Primary Content

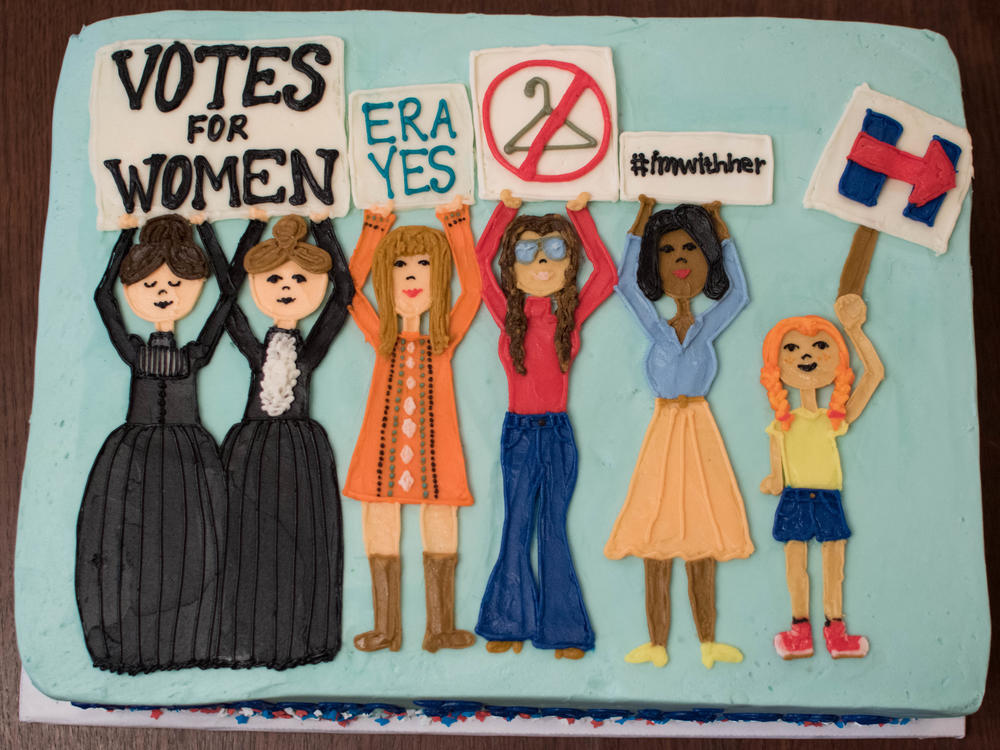

On election night 2016, Gretchen Sisson was so sure Hillary Clinton would defeat Donald Trump that she and her husband invited 80 people to their San Francisco home for a party. They even had a giant sheet cake made that celebrated suffragists and the Equal Rights Amendment. On the side was written, "Madam President."

That's not how it turned out. Trump won in a stunning outcome, and no one could bear to eat. Afterward, Sisson and her family ended up eating the cake themselves for weeks. It was, she says now, a lesson in hubris.

But as time passed, a despondent Sisson decided to channel her unhappiness into political donating, a world where women like her are increasingly making their voices heard.

This election cycle, the share of women giving money to political campaigns has already risen to 43.5% after never topping 28% in the 1990s — "a pretty significant jump," says Sheila Krumholz of the Center for Responsive Politics. (The group looked only at donations larger than $200.)

That surge provides women with greater political clout, and it could make a big difference in some of this year's closest political races.

While donations to both parties have risen, women tend to favor Democrats. President Trump has received 37% of his donations from women so far during this election cycle, while almost 48% of the contributors to former Vice President Joe Biden have been female, Krumholz says.

After Trump's 2016 win, Sisson and her husband, who owns a tech startup, donated to groups that support people they thought might be vulnerable under the new administration, such as refugee organizations and press freedom groups.

But as the 2018 midterms approached, she hooked up with the Women Donors Network and other Bay Area groups and began looking for candidates to give to directly.

"I'm an academic by training and I am really moved by a good data-driven case, and so I really started to immerse myself in figuring out where the best places to put our money would be," she says.

Early on, someone gave her a valuable piece of advice: Anyone can feel good by donating to political candidates who stand a good chance of winning already. What's harder is finding those who might be able to eke out a victory with a little financial help.

"For me, it became important to find the candidates that had a solid shot, if not a favorable shot, where money could actually move the needle," she says.

It was Moneyball meets Emily's List: Sisson learned all she could about the political leanings of various congressional districts and delved into the minutiae of Senate and governors' races. Politics became a kind of third job, says Sisson, an academic researcher with three children.

Efforts by her and thousands of other people bore fruit in 2018, when a record number of women were elected to Congress, helping Democrats take control of the House.

During this election cycle, Sisson has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to candidates, most but not all of them women, and in the process has become one of the country's top female Democratic donors. She gets dozens of calls seeking money every day.

Democrats' success in electing women to Congress hasn't gone unnoticed by Republicans.

The 2018 election may have been a huge success for Democratic women, but it was something of a debacle for their GOP counterparts, who lost almost every election they were running in.

In the election's aftermath, some Republicans have taken a hard look at the party's problems with women and decided to redouble their efforts to attract female candidates.

It hasn't always been easy, concedes Ashley Davis, a Republican fundraiser who sits on the board of Winning for Women, a political action committee headed by former New Hampshire Sen. Kelly Ayotte.

"I always joke that men feel that they were born to run for office and never have to be convinced. They have to be convinced not to run for office," Davis says. Women "need a little more persuasion about it."

Winning for Women has also sought to teach female candidates the necessary skill of asking donors for money, something women aren't always naturally good at, Davis says.

With time, the group has also had some success reaching out to female donors, and in doing that, it has learned a thing or two from the other party, she says. "I think the confidence that the Republican candidates received by watching the Democrats do it last cycle has been helpful."

One big factor driving the surge in giving by women this year may be the coronavirus. Because so much of the burden of dealing with the pandemic has fallen on women, it has spurred them to become more engaged politically, says longtime Democratic fundraiser Sally Susman.

"They're anxious. They're concerned for their families. They're worried for their livelihoods. They're worried for the future of our world," she says.

Another factor is the unprecedented number of female Democratic presidential candidates, such as Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and California Sen. Kamala Harris, now the vice presidential nominee.

"I think women are stimulated by a range of issues that are not necessarily gender specific," Susman says. But, she adds, "they get often excited by a very compelling and charismatic female candidate."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.