Section Branding

Header Content

College Political Activists Trade Door-Knocking For Apps To Register Voters

Primary Content

If this were a normal school year, Denison University senior Matt Nowling and his fellow College Democrats would be "dorm storming" around their campus, near Columbus, Ohio.

"We ran to people's dorms, knocked their doors and got them registered to vote," he said. "Sometimes we got kicked out of dorms," he added.

The start of the new school year is prime time for registering college students to vote and getting them excited about casting ballots in November — many for the first time.

But this fall, those students who can return to campus are doing so under restrictions aimed at keeping the coronavirus from spreading. That means political organizing at universities is going virtual.

For Nowling, a political science major and interim president of the national College Democrats of America organization, it's a bit of a letdown.

"All the different events that we would have in person simply can't happen. And I miss that a lot," he said.

From knocking on doors to pounding on keyboards

Figuring out how to reach people during a pandemic is hard, said Ben Rajadurai, executive director of the College Republican National Committee. He led campus Republicans at Stonehill College in Massachusetts before graduating in 2017.

"We were trained, like, knock doors, not keyboards," he said. "And then overnight, it's like, no, no, no, knock keyboards ... You quite literally cannot knock doors right now."

On campuses across the country, club recruiting fairs are happening on Zoom. College Republicans and Democrats are using Instagram and Facebook to promote virtual events. Members are swapping political memes on messaging apps like GroupMe.

"We have a group chat where people talk all the time, and it's always going," said Claire Grissum, president of College Republicans at the University of Missouri. "There are new people added all the time, hopping into the conversation."

But, she acknowledges, it's harder online to grab the attention of a student whose mind is on classes and college life, not politics. Someone who might not seek out a group chat, but would, in a normal year, engage in a conversation while crossing campus.

"School picks up and life gets busier. It gets harder to prioritize and sometimes we kind of fall off of their radar," she said. "We're hoping that there will be leniency in the [university's] guidelines for us to sit outside and [set up] table[s] ... because I know that's how we attract a lot of members that stay in our organization."

Efforts to keep increasing the student voting rate despite pandemic

With just two months to go before the election, there is a lot of pressure to get the country's roughly 18 million college students more involved in politics.

Younger people are less likely to vote than the rest of the population, but participation has been rising in recent elections.

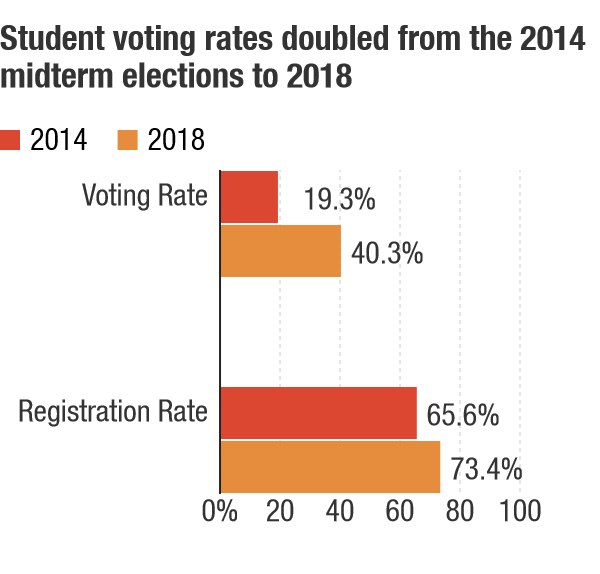

Voting rates for college students more than doubled between the midterm elections of 2014 and 2018, according to research from Tufts University's Institute for Democracy and Higher Education.

Events like this summer's racial justice protests are mobilizing college students, said Tufts researcher Adam Gismondi.

"The last few years have been a bit of a civics lesson for everyone in this country. For college students, we've definitely seen growing attention, often around specific issues," he said. "Around [the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program], around the safety of Black Americans and around the sort of unavoidable attention that the Trump administration has received."

Tech companies are also trying to help, building on voter registration efforts that started several election cycles ago. This year, Snapchat is letting people register to vote directly in its app, while Facebook has pledged to register 4 million voters by November.

Limitations of digital organizing

Campus organizers warn digital tools cannot fully replace face-to-face interaction in the brief window before election day.

"That first touch with an activist or potential voter ... it's arguably the most important contact. That conversation becomes a lot tougher in the digital space," said Rajadurai.

At Penn State University, College Democrats President Jacob Klipstein says he thinks paper registration forms are still the most accurate method of getting people onto the voter rolls. What's more, not all states allow every eligible adult to register online.

His group is planning to register voters in person on campus — with masks and other precautions.

"We're going to be using gloves. We're going to be using hand sanitizer. We're going to be using clipboards and we're going to have towels to wipe down pens," he said.

What happens if campuses shut down?

There are signs registration efforts are working. In 20 states, more young voters had already registered by this August than had done so in November 2016, according to data analyzed by CIRCLE, a Tufts University research group focused on youth civic engagement.

But many students are facing uncertainty over where to register and vote, because it is unclear whether they will still be on campus in November.

Universities are already dealing with COVID-19 outbreaks, and some are scaling back their reopening plans.

That prospect alarms Serena Ishwar, president of Ohio State University's College Democrats chapter.

"The likelihood of them saying, oh, well, the cases are too high, you guys have to go home like two weeks before the election — it really worries me," she said.

That underscores another challenge: while college activists are using all the tools at their disposal to register voters, it is much harder to get students to cast ballots. Just 40 percent of eligible college students went to the polls in 2018, a year when 73 percent of students registered to vote, according to Tufts.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.