Caption

Voters wait in an hours-long line to cast their ballot at Park Tavern in Atlanta.

Credit: Stephen Fowler | GPB News

|Updated: October 5, 2020 6:10 PM

On this episode of Battleground: Ballot Box, we hear from Georgia's Secretary of State, a county elections supervisor, a poll worker and a voter to understand the challenges that loom over a successful November election, and what steps are being done to address them.

While some issues and processes remain the same, Georgia’s voting landscape looks completely different than it did in November 2018.

For years, Republicans have dominated government at the state and federal level, but a rapidly diversifying population plus a new wave of energy behind 2018 Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams put her within 50,000 votes of becoming the first Black female governor in U.S. history.

That fierce contest between Abrams and then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp was marred by allegations of voter suppression, and cemented Georgia’s status as a battleground on two fronts: who’s on the ballot, and how those ballots are counted.

Since then, a new secretary of state took office, lawmakers approved the purchase of a new voting system, new lawsuits have been filed and a global health crisis has given state and local elections officials new challenges to make sure our right to vote is protected.

And now, ahead of one of the most important and challenging elections this state has seen, GPB News is launching this podcast to help make sense of it all.

Voters wait in an hours-long line to cast their ballot at Park Tavern in Atlanta.

In theory, it has never been easier to vote in Georgia but in reality, it has also never been easier to get confused or disheartened by very real problems that can hold people back from casting their ballot.

In this first episode, we’ll take a look at where we stand six weeks out from Election Day through different perspectives in the electoral process, from Georgia’s top election official down to a frustrated Fulton County voter.

Stacey Hopkins is a 56-year-old Black woman who lives with her family in the Capitol View neighborhood just south of downtown Atlanta. Despite her knowledge of voting and politics as an activist and organizer — or maybe, because of it — Hopkins has been let down by Georgia’s election system multiple times, in multiple ways.

“I’m still trying to figure out what happened to me in 2017 because that’s the biggest mystery still,” she said. “You know, we still don’t know. I still don’t know what list I ended up on because I did everything right.”

Hopkins and her family had recently changed addresses within Fulton County, so it wasn’t surprising to get a postcard forwarded to her new address noting she had moved.

But then, she kept reading. If she did not respond to the card and send it to her local election official, her voter registration would be changed to inactive status.

“That would have been well and good, but we had all just voted in the last election that we were eligible in,” she said. “So we had just voted in College Park where we were staying!”

Even though she moved within the same county, and filed her change of address notice, Hopkins unintentionally set off a bureaucratic process intended to cancel the voter registration of people who have died or moved out of state.

Except Stacey Hopkins was very much alive, very much a Fulton County resident and, now, very frustrated with elections officials.

“That led me to this insane labyrinth between the county and the state… the county was saying that it was state's fault, which it was,” she said. “The state was trying to blame the counties.”

The ACLU of Georgia sued the state on her behalf, leading to a settlement that would ensure other people who moved within their county would have their addresses automatically updated to avoid a similar fate.

Two years later, a new voting system, a new secretary of state, and new problems on display during the June 9 primary have left a similarly bad taste in her mouth about the state of elections in Georgia.

“It is so sad that we have reached the point we could no longer trust not only our elected officials, but we can’t even trust the systems of our democracy,” Hopkins said.

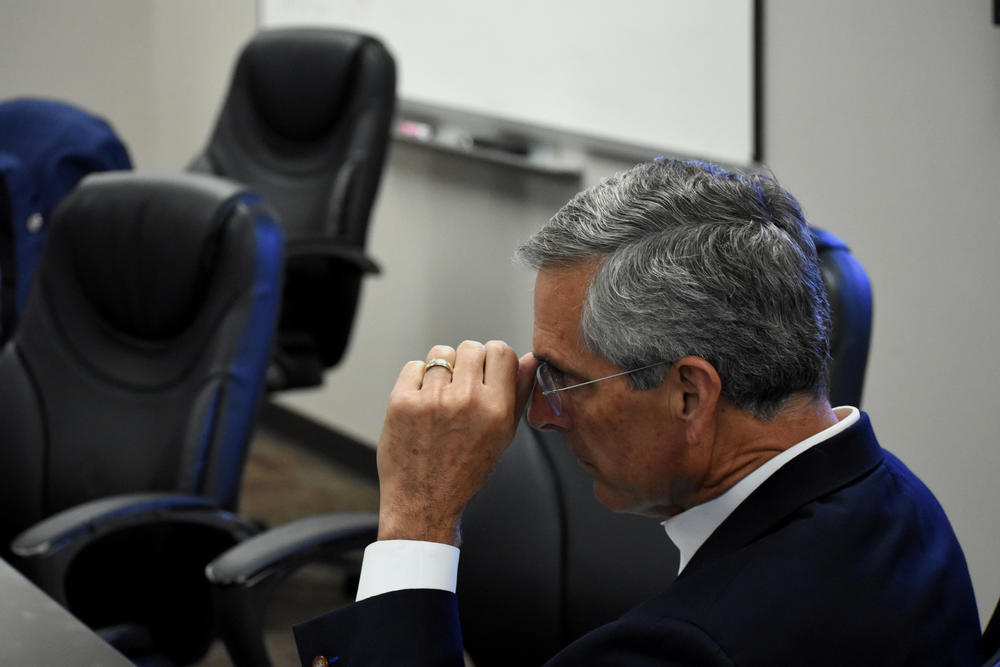

Georgia Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger listens to staff detail voting precincts open past 7 p.m. because of problems on June 9, 2020.

For the state’s chief election official, trust in the system has been tested by a global pandemic, a rapid increase in absentee voting, and the rollout of a new $104 million touchscreen voting system challenged both in court and in the court of public opinion.

“I don't know if it's because I'm a small business owner or I'm an engineer, but both of them, the market requires you to be adaptable,” Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger said in an interview. “You have to adjust. The market is never static. And obviously this year with COVID-19, the election process has not been static.”

The biggest challenge Raffensperger thought he would be dealing with at the start of 2020 was making sure all of Georgia’s 159 counties received more than 30,000 pieces of election equipment in time for early voting ahead of the March 14 presidential primary.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Raffensperger delayed the primary twice — first to coincide with the May 19 general primary, then pushing both of those to June 9 — and took the unprecedented step of mailing absentee ballot applications to 6.9 million active voters.

More than a million Georgians voted by mail, at times overwhelming county elections offices with avalanches of both applications and ballots.

The day-to-day election process is run at the local level, but Raffensperger and the secretary of state’s office act as a clearinghouse for guidance and instruction. The State Election Board, which Raffensperger chairs, also decided to allow secure drop boxes for voters to return absentee ballots and avoid human contact, and the state set up a grant program to help counties pay for them.

After the June primary, where more than 20 counties had to stay open late because of problems with lines and the new voting machines, Raffensperger said that it is ultimately his responsibility to make sure county officials have what they need to make things run smoothly.

Georgia had one of the better responses to the pandemic, Raffensperger said, and he’s confident that will continue for November — even as voters faced issues with in-person early voting, absentee by mail and, of course, on the primary's election day.

“We gave people three options,” he said. “And that really gives us ultimate flexibility.”

The Bacon County Elections Office has hand sanitizer for voters and visitors because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Flexibility is one of the few things Bacon County election supervisor Ann Russell has been able to count on this year because of COVID-19.

“We were very blessed because we had just one polling place, and my polling place happens to be here at my office so we didn’t have to worry or struggle,” she said.

The southeast Georgia county has about 6,700 registered voters and not enough space to set up its two dozen voting machines according to social distancing guidelines.

So for the primary, Russell had the county clear police cars from a garage behind the office and spread out check-in stations, voting machines and scanners to keep voters safe.

Like everywhere else in the state, Bacon County was also overwhelmed by absentee ballots.

In the 2016 presidential election, Russell counted 175 absentee-by-mail votes.

“Back in June, we counted almost 1,300 absentee ballots, so we've had to reinvent the wheel when it comes to our absentee ballots here in Bacon County,” she said. “And I know every other county has had to do that as well.”

Russell also said it is important to know that on Election Day, the work starts well before the first votes are cast at 7 A.M.

“We just don't all show up and say ‘OK! We're here!’ and then at 7 p.m. ‘OK! Let's wrap it up and go home!,’” she said. “First of all, here in Bacon County, I expect my poll workers to be here at 5:00 a.m. Me personally, I was here at 4:45 that morning and I did not walk out of here until I think 11 that night.”

And if you think elections start with the first day of early voting… think again.

From qualifying candidates to appear on the ballot to proofing the ballots for accuracy, preparations often begin months in advance. Hiring and training poll workers, mailing out ballots, processing voter registration and more happens on a constant basis.

“You would be amazed at the people that come in during early voting or even on Election Day that ask us, ‘Are you all open all year?’” Russell laughs.

Georgia’s 159 county elections supervisors are on the frontlines of making sure our constitutional right to vote is safe, secure and accessible — often with only a small staff and few resources.

One of the most important tasks is training poll workers, especially on Georgia’s new ballot-marking device system that uses a touchscreen iPad to check voters in, a touchscreen to make selections, a printer to create the ballot, and a scanner that tabulates and stores your choice.

In Bacon County, Russell had her poll workers run several mock elections until, by the end of February, she said they knew the system better than she did.

---

But all the training in the world can’t prepare you for a real-life election, as Decatur County poll manager Linda Salmon can tell you.

In June, she oversaw the Recovery fire department polling place in Bainbridge, which has about 600 active voters. But even with just a handful of in-person voters, things went wrong.

“Well, two major things that happened in the precinct I worked at … one of them had happened in one of the earlier elections, so we already basically know how to work around it temporarily until we could get someone to fix it,” she said.

After checking in voters on an iPad, poll workers couldn’t create the voter access card that would then go into the ballot-marking device.

The other problem was with the scanner.

“About five hours into the voting, our scanner went out and it would not let us scan the ballot, which is what actually casts the ballot,” Salmon said. “So we had to go to the emergency ballot box and let the people actually put their ballot into that emergency box until Carol could come out to take a look at it.”

Carol Heard, the elections director, came out to fix the scanner and the rest of the day was uneventful.

Salmon first volunteered as a poll worker after a friend recruited her in 2008.

“I'd always thought that it was really important to vote, but I had never thought about all of the work that goes on behind the scenes to make that happen,” she said. “So once I did it the first time, I realized how important it is to have people that are dedicated and how lucky our county is to have those people that are willing to go through all the training. I guess that was the beginning of filling a real civic duty to do it, you know? I mean, it's really a privilege to be able to do it.”

She’s been through hours and hours of training, and feels encouraged by how many voters she works with that take their right to vote to heart, even in the pandemic.

But even if the state supports the counties, and the counties properly train the poll workers, there are still voters such as Hopkins who face challenges with voting in Georgia, most recently in the June primary.

“I filled out three applications, I walked three applications down to Fulton County, and only one person got their ballot in our household,” she said.

Hopkins doesn’t trust the new ballot-marking devices with their large touchscreens, and what she says is a considerable cost passed on to local elections officials, but she still said it is imperative for you to cast your ballot this fall because of and in spite of the challenges she and others may face.

“All I care about is that you have the opportunity to have your say, and to unilaterally disarm myself and other Black and brown people from having their say, it sends a message to us that you really don't care,” she said. “You don't want to hear what I have to say, what my neighbors have to say, what anyone has to say, and that sends a message that is so disheartening and so infuriating in this state.”

Hopefully, Hopkins said, Georgia can get it together and give its seven million voters plenty to trust.

“But I have to be honest: I don't think I'll live long enough to see that.”

---

In this podcast over the next several weeks, we are going to go on a journey through Georgia’s election system and hear from experts and officials and ordinary people to detail some of the barriers to the ballot box — but more importantly, how those barriers can be overcome.

This is not a series to scare you away from voting, or to make you feel that your vote does not matter. This is also not a whitewash of the very real challenges that keep people from casting their ballot, or the history of difficulties that make it harder for certain communities to participate in our fundamental right to vote.

This is a chance to take control, to gain understanding and to make a plan to make your voice heard.

Battleground: Ballot Box is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. You can subscribe to our show at gpb.org/battleground, or anywhere you get podcasts.

Please leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts.