Section Branding

Header Content

There's No 'Convenient Structure To Life,' Says Allie Brosh

Primary Content

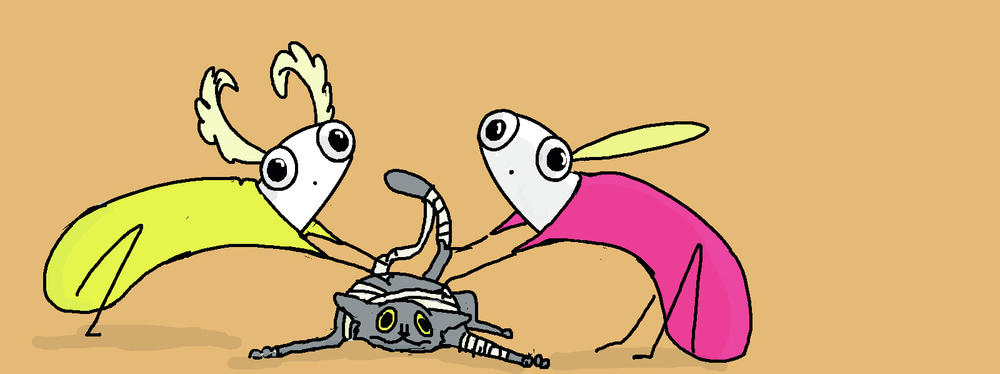

There's this one story, in a new book by comic artist Allie Brosh, where four guys dress a dog in a humiliating costume and parade him down Las Vegas Boulevard — all to celebrate some human's birthday. Needless to say, the dog is confused, and overwhelmed.

"I think I also relate to how confused they must feel all the time," Brosh says. And when she watches her own pets, she wonders, what the heck goes through their minds?

"My cat, yesterday, he made this guttural sound I'd never heard before in my life — kind of like 'RAUUUUHHHH.' And then he makes a sound like 'trrrrrrl' and comes running downstairs. Nobody knows what to do. I don't know what he's trying to tell me. But somehow we make this little connection with each other, and then it's OK."

Brosh brings these stories to life in her new graphic memoir, Solutions and Other Problems, where she reminisces not just about pets but also about weird childhood friends, painful relationships and devastating loss.

Interview Highlights

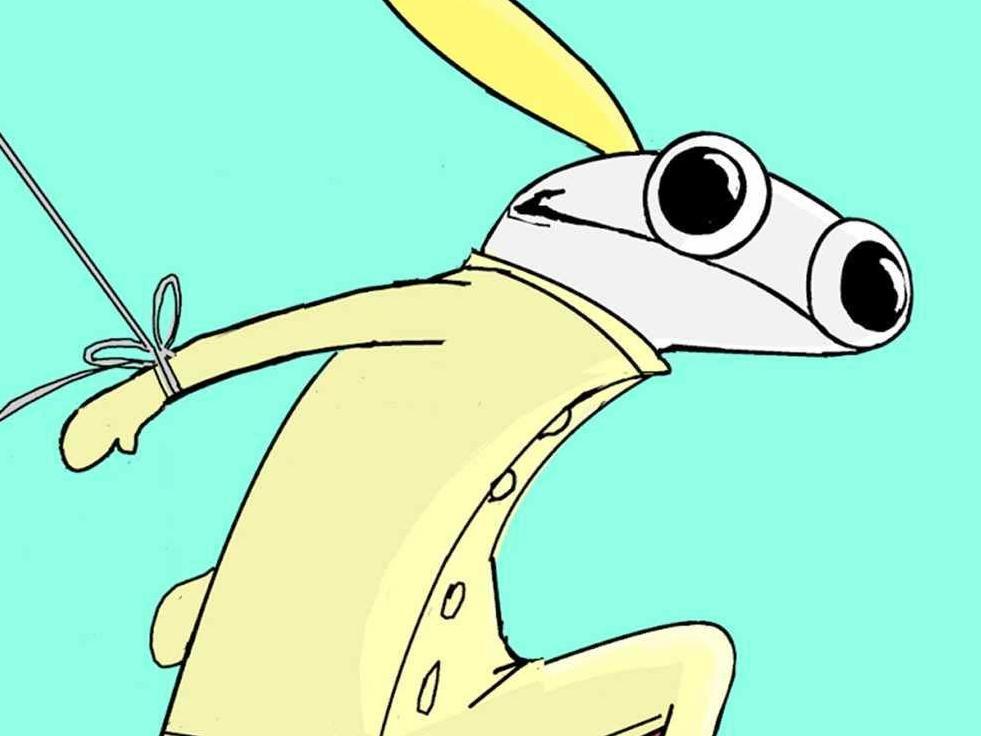

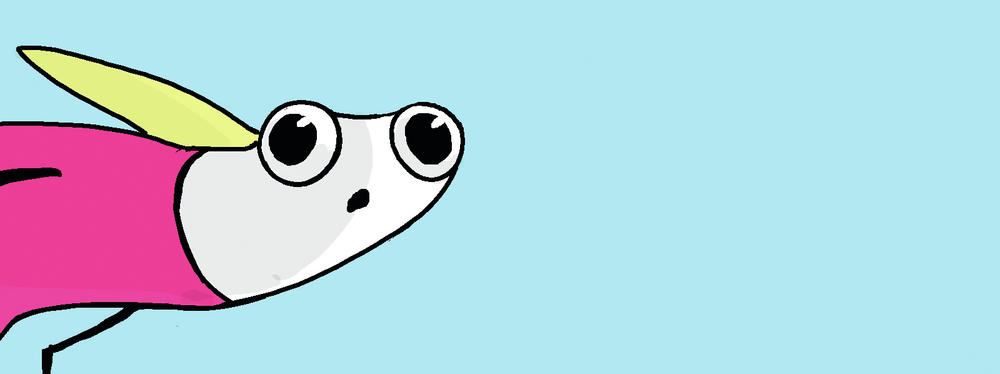

On her bug-eyed cartoon avatar

I feel very awkward a lot, and so I want to represent myself with this awkward thing, this thing that doesn't quite look like a person. Maybe it looks like some sort of bug or some sort of alien, because that's how I feel. It helps when I'm trying to communicate how I feel to other people. It helps with setting the context and the tone.

On zigzagging between zaniness and devastation

So I think that is kind of the way it is in life, how it really goes. There's no, like, convenient structure to life and to the stories that are unfolding in real time. And we can try to package them in these convenient ways, where everything makes perfect sense and this act leads to this act, but I don't think I really wanted to do it that way. I wanted it to be a little bit more of a chaotic but real reflection of how these things actually felt. And the most authentic way I knew how to do that was by just trying to capture it and changes in tone in these ways where it's like, you know, you can have a moment of great hilarity followed by a moment of sorrow or the inverse.

On what needed to happen before she could publish this long-awaited (and long-delayed) new book

So I think the first time that I was going to publish the book — and I was very far along in the process — I think I was at a strange point in my life where I hadn't quite figured out what I wanted to say and who I was. And so I think it was more of just giving myself time to get settled in myself so I could say what I wanted to say more effectively. But there were certain pivotal experiences that I hadn't had yet that turned out to be very, very important for what I was trying to say.

On her sister's death

All right. Warning. I'm probably going to start crying. So there's a saying like, familiarity breeds contempt. What isn't quite so obvious is that the parts that are really special about these relationships that have maybe even been kind of challenging — and I think my sister and I had that kind of relationship — there were fleeting moments where I would realize things like, you know, I'd see something she would post on Facebook and it would make me laugh. And I would have an appreciation for, like, how amazingly funny she is. But I don't think that those things were as clear to me as they are now until I lost her. I think one of the greatest feelings of loss I felt was, I had this realization after, like after it was no longer possible to tell her. And I so deeply wanted to.

You know, I think that there are things that she and I really could relate to each other, about more than anybody in the world, that we grew up together, we understand each other's context. When she was horribly depressed and there were conversations we would have where she described just staring at the wall all day because she didn't know what else to do. And I've been there. A few weeks before she died, we had a conversation like that, and I think it was meaningful. I hope it was it felt meaningful for her as well. But I don't know. I think I could have been a better big sister.

On learning how to become friends with yourself

So I think it at some point became necessary, because I think there are a lot of experiences that a person can have that make them feel very unsympathetic toward themselves, in the same way that, you know, the familiarity breeds contempt. Well, like, what's the most familiar thing that anybody has? Themselves! In the same way that I had this relationship with my sister that I didn't realize was so special, I think within ourselves there's that same thing. There's one person in the world who has seen everything that you have ever been through and understands what it felt like. And that person is yourself. And I found tremendous comfort in very dark times from thinking about that, at times where I felt more alone than I can even really describe. There was this one moment where I was, I felt desperately alone and sad and I had the idea to, like, grab my own shoulder with my hand in sort of like a comforting gesture and just say it's OK. And you know what? It felt like a friend doing that.

This story was produced for radio by Elena Burnett and Christopher Intagliata and was adapted for the Web by Petra Mayer.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content