Caption

State program doesn't collect data or process complaints on funds designed to help lower income families.

Credit: Pragyan Bezbaruah on Pexels.com

|Updated: October 2, 2020 4:44 PM

State program doesn't collect data or process complaints on funds designed to help lower income families.

In 2008 the Georgia Legislature created a program for taxpayers to fund private school scholarships, promising the measure would pressure low-performing public schools to improve, reduce local and state taxes and help lower-income children stuck in bad public schools.

Since then, more than $600 million has been shifted from state coffers to elementary and high school scholarships at private schools around the state – including more than 40 in the Savannah area.

An investigation by The Current suggests that over the last five years the law has fallen short on a key promise: serving the state’s economically disadvantaged children.

The state cedes as much as $100 million a year to private, nonprofit Student Scholarship Organizations (SSOs), which distribute scholarship funds.

State records reviewed by The Current reveal that the tax credit favored children from middle-class and wealthier families over those from low-income backgrounds. They also show that state agencies failed to verify annual reports from the scholarship funds or provide oversight.

In one case, state officials allowed a man guilty of securities fraud to manage more than $700,000 in scholarship money. The Legislature, meanwhile, has made it a criminal offense to make financial details of the program public.

The state cedes as much as $100 million a year to private, nonprofit Student Scholarship Organizations (SSOs), which distribute scholarship funds.

The Current’s analysis of data from 2015 to 2019, collected from the Departments of Revenue and Education, the agencies that oversee the SSOs, as well as interviews with policy experts, state officials, legislators and school officials, shows that even the most basic information — which schools are receiving scholarships — is impossible to find, as the state does not require SSOs to report this information. Last year, Georgia had 22 registered SSOs.

The lack of information makes it difficult for supporters of the law, as well as detractors, to tell what effect the program has had.

Kyle Wingfield, president of the conservative Georgia Public Policy Foundation, says the tax credit could be saving the state money but concedes that it’s difficult to know for sure. “It almost certainly, in our view, is at least budget neutral, and probably budget positive,” Wingfield said.

Steve Suitts, adjunct professor at Emory University, says the law amounts to nothing more than an unregulated handout for private schools. “If there is a worse piece of legislation being passed around, I don’t know about it yet,” he said.

The Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit, as the Georgia law is called, resembles those in the 18 states that have similar programs designed to boost school choice.

Individual taxpayers can receive a credit of as much as $1,000 of their state income tax by filling out an application. Couples are eligible for $2,500, and corporations can credit up to 75 percent of their state tax liability.

Georgia is one of six that doesn’t take into account family income when determining who is eligible for scholarships, according to a review of data collected by EdChoice, a nonprofit that advocates for school choice. Georgia SSOs “consider” financial need but are not required to base scholarships on it.

In 2009, former Gov. Sonny Perdue pushed for sweeping reforms. Among other things Perdue wanted the program to do more to favor low income children, and to require background checks on SSO owners and operators. Six states require background checks on scholarship organization board members and employees.

His proposal sought to track the performance of students who received the scholarships and to prohibit SSOs from also operating schools that receive the scholarships. Finally, Perdue sought to require that SSOs report to the state the number of students receiving scholarships and the schools in which they are enrolled.

Perdue’s reforms died in a House committee.

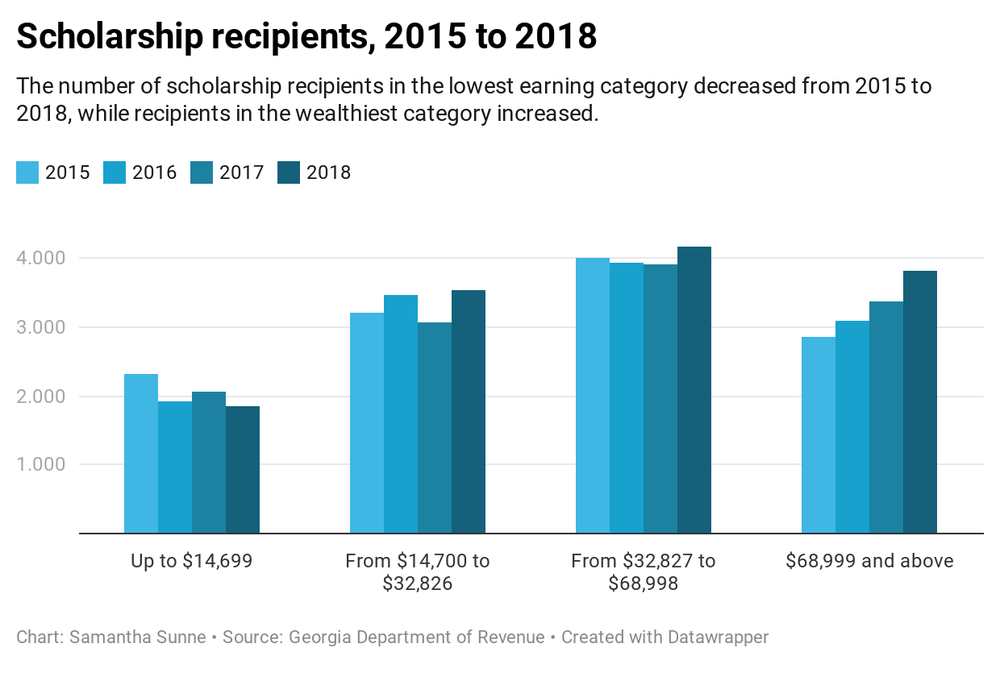

Without Perdue’s reforms, lower-income students have had less access to scholarship funds than wealthier children, according to the data analyzed by The Current. From 2015-2018, about 16 percent of scholarships have gone to the lowest income quartile of earners, Department of Revenue records show. That percentage has decreased year over year, while the percentage going to high earners has increased.

From 2015-2018, about 16 percent of scholarships have gone to the lowest income quartile of earners, Department of Revenue records show.

From 2015 to 2018, 58 percent of scholarships went to children from families making more than the state’s median income of $32,827, The Current’s analysis of state records shows.

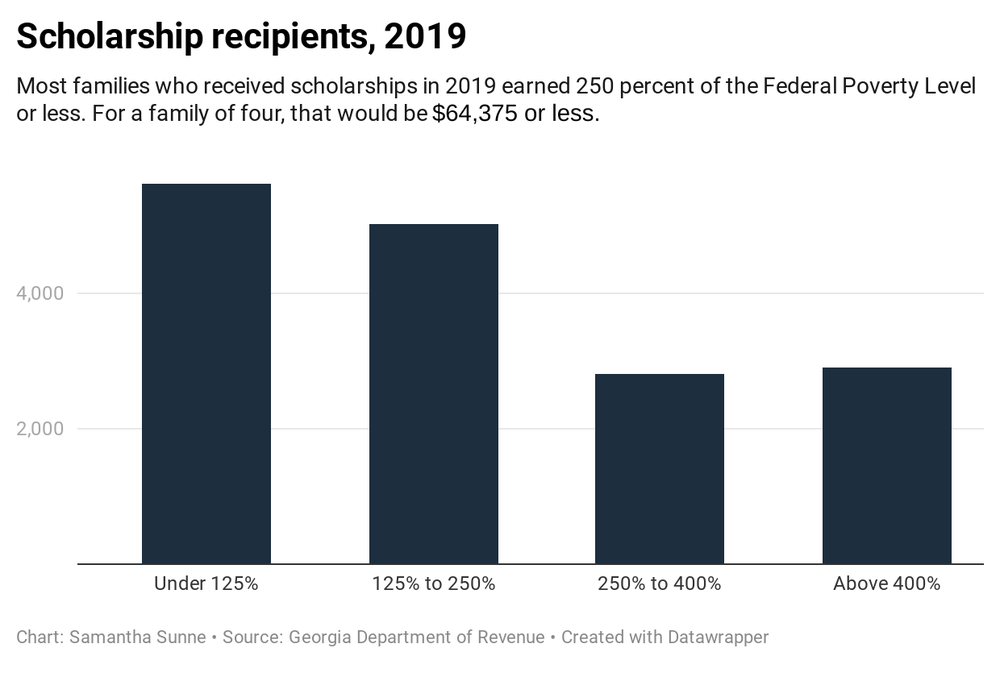

In 2019 the legal reporting requirements changed. Data from the state Revenue Department shows that in 2019, 65 percent went to families earning 250 percent of the federal poverty level or less – for instance, a family of four earning $64,375 or less. The state does not record recipients’ family size, which is needed to calculate the federal poverty level.

Some scholarship organizations do direct their scholarships to lower income families. The largest SSO in the state is Georgia GOAL Scholarship Program, Inc., which funded 5,855 scholarships in 2019 totaling more than $28 million, Revenue Department records show.

Georgia GOAL gave 59 percent of its scholarships to the lowest earning families. GOAL scholarships account for about a third of all scholarship money in 2019, Revenue Department records show.

The second-largest SSO in Georgia is Apogee Georgia School Choice Scholarship Fund, which distributed nearly $11 million to 2,157 recipients, Revenue Department records show. Apogee provides scholarships to Savannah Country Day and a dozen other Savannah schools, among more than 150 different schools around the state.

Last year Apogee allocated almost half of its scholarships to the wealthiest category of recipients, whose families earn more than 400 percent of the federal poverty level, for example, a family of four earning at least $103,000.

About 15 percent of Apogee’s scholarships went to students in the lowest income category, who earn 125 percent of the federal poverty level or less, Revenue Department records show.

On average, the wealthier students also received larger scholarships. Apogee reported to the Revenue Department that it gave an average of $5,178 to the lowest-income students and $5,341 to the highest.

Apogee CEO Kevin McGrath did not return several requests for comment.

The Current asked 10 Savannah schools how much they receive in SSO scholarship money, but none responded.

ALEF Fund, which donates to JEA Preschool Savannah and other Jewish schools, allocates more than half its scholarships to families in the wealthiest category.

Georgia Tuition Aid Providers, an SSO based out of a private home in Cumming, gives about 90 percent of its scholarships to students with the highest incomes. Last year it gave 43 scholarships to students in the highest-earning category, and five to everyone else.

While the state doesn’t require scholarships to be given to low-income students, it is supposed to ensure that the organizations managing the funds are businesses in good standing.

Even in this, the state has a spotty track record.

To qualify an SSO must be registered as a nonprofit. They also are required to provide annual financial reports to the Department of Revenue that show how much scholarship money they received and spent.

The SSOs qualify for the credit by submitting annual reports to the Department of Education assuring that they are complying with the law.

However, some of these requirements, such as the organizations’ registration and nonprofit status with the Secretary of State, are not verified, according to Department of Education officials.

Christian International Counseling & Ministries, an SSO headquartered in suburban Atlanta, reported awarding $704,740 in scholarships last year. But the organization didn’t mention that its president is facing up to 20 years in prison for a global hacking and investment fraud scheme.

Arkadiy Dubovoy, a Ukranian-American and devout Christian, used altered financial documents and paid hackers in Ukraine to steal financial press releases that he leveraged to make insider stock trades. His ring of securities traders targeted Home Depot, Panera Bread Co., Hewlett-Packard, and Caterpillar among other companies, according to federal prosecutors. Dubovoy pleaded guilty in 2016, reached a civil settlement for securities fraud this summer, and is awaiting sentencing.

All of Dubovoy’s businesses were dissolved by the Georgia Secretary of State for failing to maintain annual registration.

Despite the four-year Securities and Exchange lawsuit, Dubovoy’s SSO has successfully registered for the school tax credit program every year except 2015, the year he was arrested. Last year, his SSO qualified for more than $700,000 in state tax credit dollars.

Serge Kulinich, who manages the SSO, said it reports its activities truthfully and that Dubovoy is not involved with its day to day matters.

Some SSOs licensed to handle Georgia taxpayer funds didn’t meet the requirements for registration.

Ramah SDA Junior Academy, a K-8 school in Savannah, is registered as an SSO while also being a private school itself. Officials at Ramah did not return requests for comment.

Last December, Jamila Suber turned in the necessary form to the Department of Education to register Northwest Georgia Scholars Program, Inc. as an SSO. Based outside of Atlanta, Northwest distributed about $50,000 in scholarships from 2017 to 2019.

Yet the organization had been involuntarily dissolved by the Secretary of State in 2017. The State appeared not to research this fact when it added Northwest to the list of 2020 registered organizations.

After The Current reached Suber in September 2020 to explain this apparent anomaly, she filed the paperwork Sept. 4 to allow her SSO to be reinstated as an active business, according to Secretary of State records.

“There was nothing intentional about our process, approach, or operating procedures that would warrant we be in violation or any way concerned about this statute,” Suber said in a subsequent interview. She said the Department of Revenue had never notified her of a concern or penalty.

“You’re painting a negative picture that’s apparently fake news-worthy,” said Suber, a private equities investor in the Atlanta area.

Meghan Frick, Director of Communications for the Department of Education, said the department would take action if it received notice of a noncompliant SSO, but said the office does not have a formal investigation process.

Julie James, a paralegal with the department, told The Current that employees “did not recall” investigating any SSOs.

However, James said she wasn’t certain because one employee had deleted their relevant emails. State employees are forbidden by law from intentionally destroying state records including official emails.

Frick said the employee’s deletion was a misunderstanding. “We will work with this employee, and the staff as a whole, to ensure a better understanding of records retention obligations as they relate to electronic files,” she said.

The Department of Revenue publishes the names of SSOs that it finds violating the rules, usually based on audits.

Jessica Simmons, deputy commissioner of the Department of Revenue, said the department fulfills its legal responsibilities and declined to elaborate.

Of the 18 states that have similar programs, Georgia is among those with the fewest regulations and disclosures, a review of EdChoice data shows. Among the 18, Georgia, Utah and South Carolina require the least financial, performance and detailed information from schools and scholarship organizations.

In Florida, for example, student scholarship organizations must provide the state’s Department of Education with demographic information for each student, including name, date of birth, social security number, grade level, gender, race, parent’s name, and address four times a year. Teachers in schools that receive tax credit scholarships in Florida must have bachelor’s degrees.

Unlike Georgia, Florida schools also are required to comply with local health, safety and welfare laws, the EdChoice data shows. Teachers and school employees must also submit to a federal background check.

Florida also mandates that private schools complete annual surveys and to make public their scores of standardized tests. The state publishes quarterly reports on the tax credit scholarship program and its affiliated schools and students.

Under Georgia law, the Department of Revenue can only publish aggregate information, like totals of tax credits and scholarships awarded. It is a criminal misdemeanor to make public any additional financial information on the SSOs – including their state mandated audits.

To critics of the law, this lack of oversight is troubling. “It feels like we really are just throwing 100 million dollars into a black box every year,” said Stephen Owens, an education policy analyst at the Georgia Budget & Policy Institute, a progressive-leaning think tank.

A lawmaker in 2008 argued that state and local governments could save nearly $100 million a year because about 15,000 students would transfer to private schools. The vacuum of data about the law keeps proponents and critics from evaluating whether the tax credit program saves the state money.

The only reports that have attempted to quantify this hypothesis are years old — and offer contradictory results.

A 2016 report by EdChoice found the program may have saved the state more than $7 million in one year. A 2014 study by Georgia State University found it may have cost the state as much as $32 million. To know for sure, one would have to know how many students were convinced to transfer out of public schools, data that is not tracked in Georgia.

While the tax credit has not directly siphoned money from Georgia public schools, lawmakers have reduced education funding by $8.79 billion since 2008, the year the tax credit began. The tax credit totals 1.04 percent of this year’s public education budget.

Buck Alford, director of communications and development for the Arete Scholars Fund SSO, considers the lost revenue to be inconsequential.

“It’s not like money is being pulled out of the state’s budget or the general treasury. These aren’t public funds,” Alford said.

Wingfield, of the conservative Georgia Public Policy Foundation, said the school choice program has changed over the years to encourage more transparency.

“You have some very vocal critics of the program in the legislature,” he said. “I would venture to say it’s one of the more scrutinized programs, certainly in the public debate.”

A 2016 report by the Institute for Justice found that the private school tax credit was the fifth-largest in Georgia, as a total of dollars diverted from tax revenue. The four largest were for films, low-income housing, employers and taxes paid in other states.

Legislators often cite low revenue as a reason for education cuts. Yet Rep. John Carson, R-Marietta, feels that SSO critics are more concerned with money than with students.

“If you’re opposed to this $100 million per year program, then why are you not opposed to the Georgia Film credit at $800 million per year, or the Low Income Housing Credit at $250 million per year, or the Job Investment R&D Credit at $300 million per year?” Carson asked.

Emory University’s Suitts counters that the mere existence of the tax credit undermines opportunity for low income children in the state, given the lower revenues available for public schools and the lack of opportunity that the school choice program actually provides them.

“The fact is, the smallest percentage of students receiving these tax vouchers are from the lowest income families,” he said.

Meanwhile, Alford of the Arete Scholars Fund says he’s confident that his 10-year-old fund has realized its goal of helping kids get educational opportunities they would not normally get.

“It could still use design improvements legislatively,” he said of the tax program. “But it has come a long way since that first version in 2008 and has been a wonderful tool for a lot of great work.”

For parents around the state eager to have enough data to draw their own conclusions, they will have to wait until 2023, when the state auditor will publish its first economic analysis of the SSO law for the House Ways and Means Committee.

Anna Kim and Dan Schwartz contributed reporting to this story.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, an independent, in-depth and investigative journalism website for Coastal Georgia.