Caption

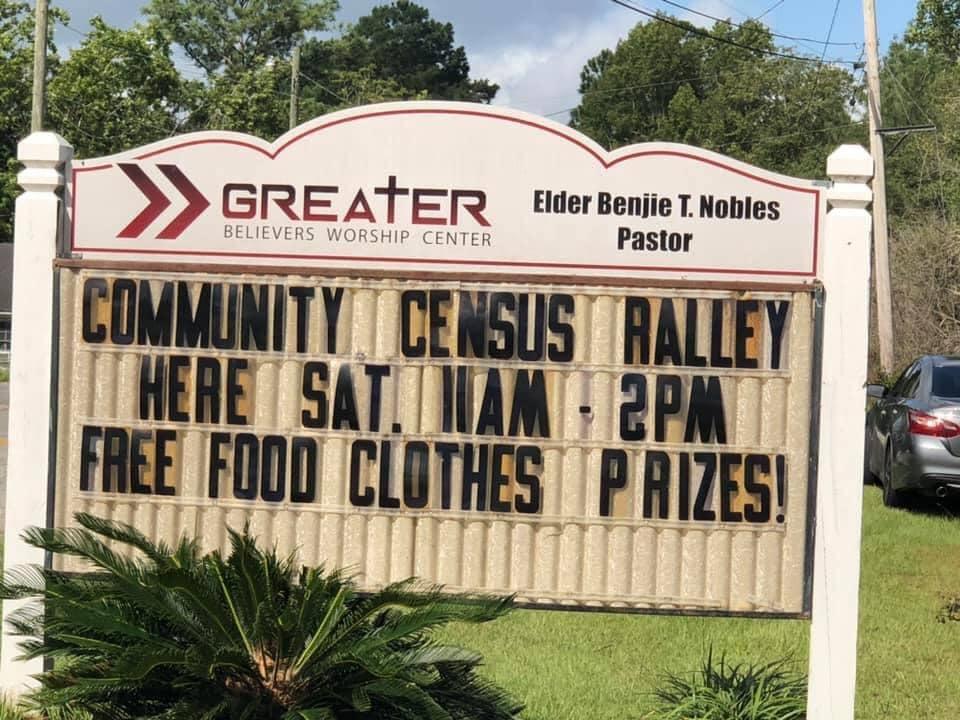

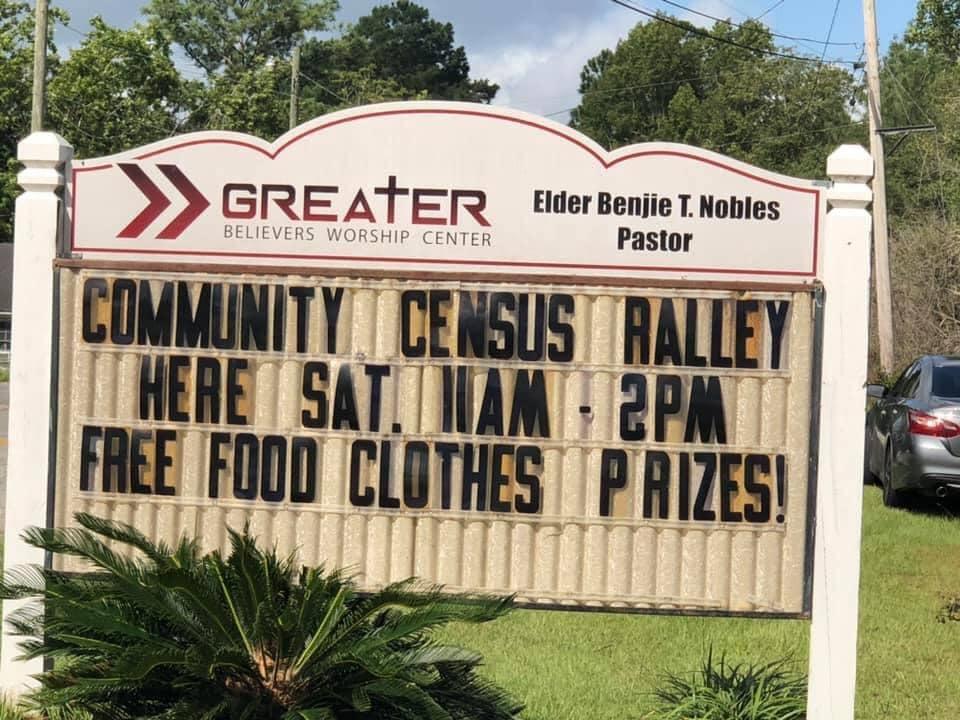

Pastor Benjie Nobles believed it important to host a Census gathering to help the minority community of Moultrie to be counted.

Credit: Greater Believers Worship Center

|Updated: October 1, 2020 12:24 PM

Pastor Benjie Nobles leads a U.S. Census rally outside his Moultrie, Ga., church in Colquitt County, a place best known for its powerhouse high school football team and the world-famous Moss Farms Diving Tigers.

Colquitt County brims with outsized fields of cotton, peanuts and tobacco. It is commonly billed as the No. 1 agricultural county in Georgia, and hosts the Sunbelt Ag Expo every year, one of the largest farm shows in the Southeast. Vice President Mike Pence stopped in town in 2018 to speak at the annual event.

Pastor Benjie Nobles believed it important to host a Census gathering to help the minority community of Moultrie to be counted.

But the community has not gone unscathed during the coronavirus pandemic, with more than 30 people dying from the virus and nearly 2,000 people falling ill.

Another effect of the pandemic: COVID-19 has made the Census task of knocking on doors and collecting numbers of how many people live here exceedingly difficult.

Amid this small-town backdrop of beautiful Georgian revival homes and a meticulously maintained town square in Moultrie lies an intense effort by a small and diverse team to count all the numbers necessary — with the Census deadline fast approaching.

With the rural community struggling to get people to participate in the census, Nobles of Greater Believers Worship Center said he sought to help in any way possible.

“Be part of the solution,” he said, “and not part of the problem.”

Bertha Riojas-Jasso drives out into the most rural stretches of the county to meet with migrant workers. Many are undocumented and are skeptical of giving any information to the government, especially at a time of heated anti-immigrant rhetoric in America.

“They are scared,” said Riojas-Jasso, who came to Colquitt County from Mexico more than 30 years ago and whose first job was working in the fields.

She tries to convince these immigrants that, in this case, the government doesn’t care about their immigration status — that the census information is vital for funding for everything from lunches at schools to special health programs to housing.

“They say, ‘What is this for?’’ Riojas-Jasso said. “So, I explain it to them.”

Barbara Jelks, a county commissioner, knows all too well the skepticism Riojas-Jasso faces. An advocate for the Black community for decades, Jelks has witnessed a healthy dose of mistrust from that community.

“The challenge that I see is just getting people involved,” Jelks said. “In order to get people involved, you have to make them understand the real need for this.”

“A lot of people,” she added, “just feel that their vote doesn’t count.”

At stake, officials say, is $500 million for a county where 25% of people live below the poverty line. In the city of Moultrie, that number is much higher, with 36% living below the poverty line.

And that is why there is a flurry of activity to make sure as many people are counted, so the county doesn't lose out on any of the much-needed funding.

'The stakes could not be higher'

Nobles, Riojas-Jasso and Jelks are among the warriors on the front lines of getting the word out for people here to take part in Census 2020 — that it’s imperative for people in this rural county in southwest Georgia about 30 minutes from the Florida border to be fairly represented.

Barbara Jelks likes spreading the word on the importance of the Census. "You have to make them understand the real need for this," she said.

The funding helps pay for more than 300 federal programs in Georgia, from Medicaid to school lunches and from water management to wildlife restoration. Additionally, census data every 10 years determines the number of seats a state has in the U.S. House of Representatives and how many electoral votes a state gets. Corporations also use the information to help determine where to open factories and offices.

But this year has been especially difficult for those trying to get an accurate tally of communities, with the Census Bureau suspending field operations in March due to the coronavirus pandemic and later extending the counting deadline through October.

“We’ve had to overcome a lot of barriers as a community,” said Sarah Adams, the University of Georgia Archway professional for Colquitt County.

Adding to the difficulty, this summer the Trump administration unexpectedly cut short the Census deadline by a month to Sept. 30, only for Judge Lucy Koh in the Northern District of California last week to reimpose the deadline of Oct. 31.

Further sowing confusion into the process, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has since said he intends to end the Census count Oct. 5 despite the court ruling.

To date, Georgia ranks 47th in the nation in its response to the Census with a response rate of 96.4%, with only Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana and South Carolina having lower participation, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Those figures include the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

About $1.5 trillion in federal funding is at stake across the country. Illustrating the importance of Census data, one document shows Georgia received nearly $24 billion from 55 federal programs in 2017.

“Literally, the stakes could not be higher,” Gov. Brian Kemp said last week, urging all Georgians to take part.

In Colquitt County, the self-response rates stand at just over 50%, making it 102nd out of the state’s 159 counties, officials say. In 2010, the county had a self-response rate that hovered around 71%.

Throw in a shortage of workers and an American public more skeptical than ever of the federal government, the challenges, at times, seem monumental.

One worker in Colquitt County said she quit her Census job due to bureaucratic red tape and issues with the cellphone provided by the agency. Susie Magwood-Thomas said she waited three days for assistance from the internal Census technical assistance service line. Because of the delay, she felt that she couldn't rely on the phone just in case there was an emergency.

“If I was in a situation by myself out there,” Magwood-Thomas said, “who’s going to help me?”

Forced to adapt

Adams has been working to build awareness in Colquitt County through the Complete Count Committee, which is charged with developing the state’s Census 2020 outreach efforts. The Archway Partnership she works for helps connect the University of Georgia and other educational institutions.

Sarah Adams, on the right, and Barbara Grogan occupy a Census booth at the local Waffle House.

She said the work is too important. It comes at a time when America is shifting greatly with more and more minority communities. Colquitt represents that diversity, with a growing Latino and Black community, and Census 2020 must reflect that changing reality, she said.

“Demographics are a huge part and we don’t want anyone to be undercounted, because that’s where that lack of equity is exacerbated,” Adams said. “A lot of it is just bringing the right people to the table. You have to set up a platform for people to be well-represented in your community.”

The pandemic was “catastrophic” on their work, she said, because the virus outbreak arrived in the spring just as census workers were planning to hold informational events in front of grocery stores, laundromats and health clinics around the county.

“A lot of those in-person events didn’t happen,” Adams said.

In normal times, the Census launches April 1 and ends at the end of June. The suspension of work brought on by the pandemic added another 120 days.

Adams said the pandemic forced the Colquitt committee to adapt in reaching “hard-to-count” populations. They created messages in English and Spanish for students to take home, as well as found other ways to be creative in getting the message out.

“You could reach them online,” she said, adding that they made announcements via the radio, social media and email. “We tried to be mindful of email fatigue because everybody went virtual once the pandemic hit.”

In a Complete Count Committee meeting in late September, Census Bureau Southwest Georgia Partnership Specialist Sherrell Byrd praised Adams’ efforts and everyone else’s work here

“You all have been the pacesetters,” Byrd said. “It just shows you truly care about your community, and you care about doing whatever it takes to get the count.”

' ... because you are a person'

Around the county seat of Moultrie, the recent efforts are palpable. Census information booths have informed people about the census at the Piggly Wiggly grocery store and at City Hall. Announcements boom from the speaker systems on Friday nights at the Colquitt County Packers’ high school football games. The local Waffle House gives out free waffles to entice people and let them know about the importance of signing up.

Bertha Riojas-Jasso says it is important that all residents of Colquitt County get represented in the Census.

Memorial Baptist Church in Moultrie held a food drive and census event with people turning out in droves. A Latino student group at the local branch of the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine has worked to spread the word, too.

The county has become increasingly diverse, with the Latino population skyrocketing over the past couple of decades. If one steps into a shop on Main Street along Moultrie’s town square or attends a Friday night football game, one can hear Spanish spoken as often as English.

Billboards in Spanish are common around Moultrie, and bustling stores, restaurants and supermarkets have cropped up to cater to the Latino population.

Riojas-Jasso has a small booth set up inside Rayon, one of the Mexican groceries in town. In the back, there’s a restaurant; in the front, a vast array of items labeled in both English and Spanish.

Riojas-Jasso, a program assistant with the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program, said she will continue going into the migrant communities to get as many people counted as possible.

“I know the needs of my Spanish communities,” Riojas-Jasso said.

She said that families matter. “You need to be counted because you are a person,” she tells them.

Jelks echoes that sentiment, telling those who may not want to participate that the Census helps improve the community. “We just want you to know that you are a warm body in Colquitt County,” she said.

Pastor Nobles said he felt obligated to encourage residents to participate more. He said the pandemic served as an “unseen enemy,” rightly frightening many in the community. But he said people should not let that fear prevent them from being counted — that the Bible teaches one to have a “reverential fear.”

“Knowing it’s an unseen enemy,” the pastor said, “we still have to live our lives. We still have to carry those daily tasks and missions and goals.”

This story comes to GBP through a reporting grant from The Fund for Investigative Journalism. It was edited by GPB's Wayne Drash.