Section Branding

Header Content

Political Rewind: Renowned Epidemiologist Dr. Bill Foege On Ethics, Plan For COVID-19 Vaccine

Primary Content

Several different COVID-19 vaccines are currently in trial, as companies try to quickly develop a safe, reliable and effective vaccine to be approved and distributed. But when a vaccine does become available, who gets first access — and why?

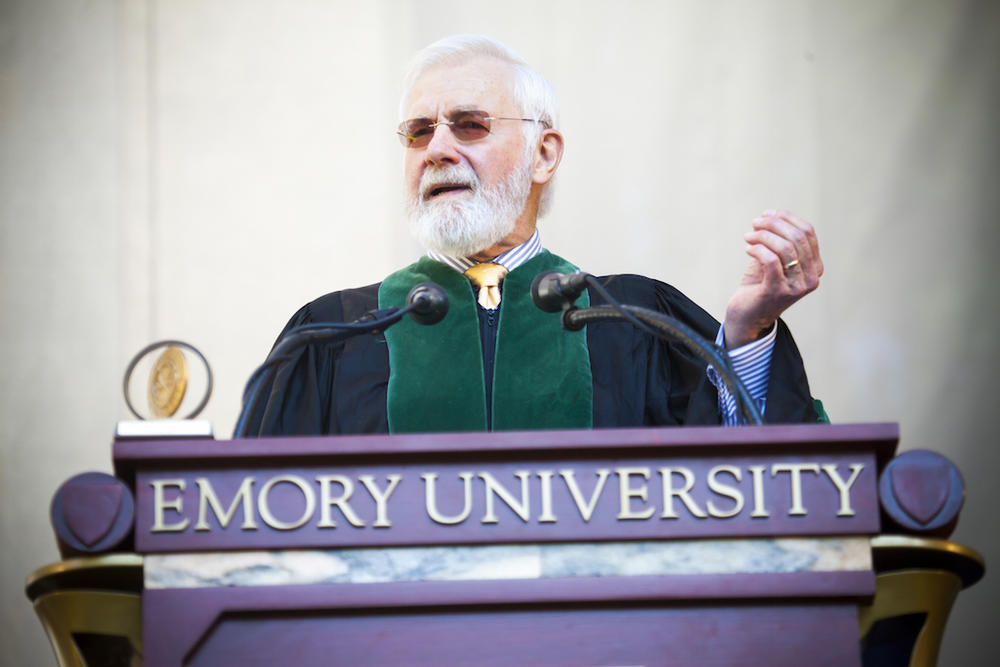

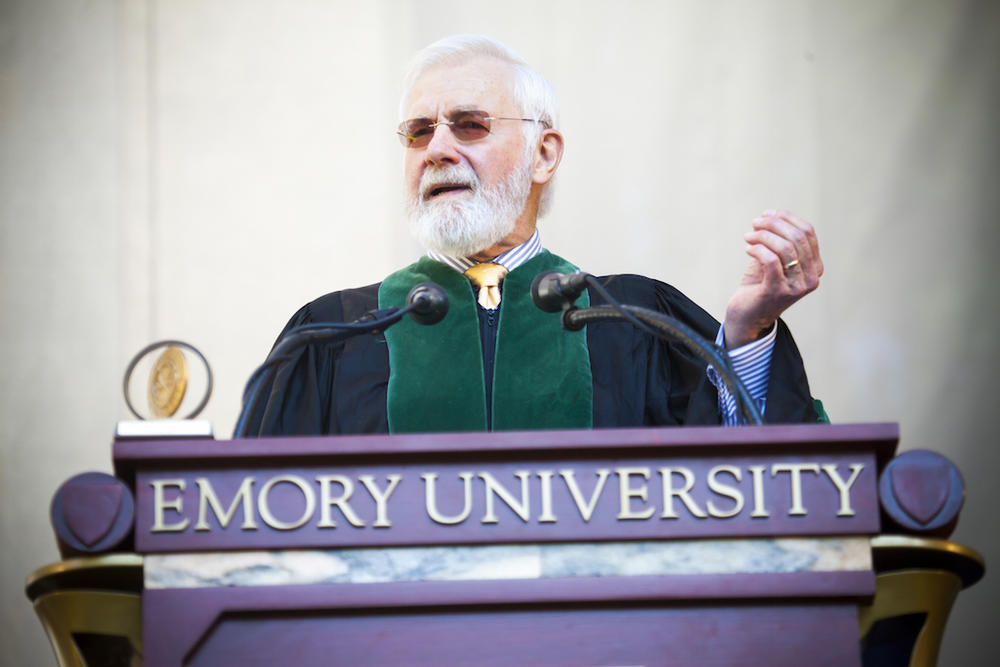

On Monday's special edition of Political Rewind, we speak with Dr. Bill Foege. He is co-chair of a National Academy of Medicine panel of public health experts tasked with devising the logistical plan to distribute a future COVID-19 vaccine.

Foege served as the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 1977 to 1983. In that role and others, he developed effective vaccination campaigns in countries across the world, including for one of the most devastating viruses in history: smallpox.

In 2012, Foege received the Medal of Freedom at the White House from President Barack Obama, who called the epidemiologist a leader in the world of vaccine distribution and public health.

For the past several months, Foege and the public health panel wrestled with complicated ethical and medical questions. Who will be the first to receive a limited vaccine supply? When will the vaccine be available to all, and who will pay for the protection? What does equitable allocation of a vaccine actually look like?

Now, the panel has released a plan that breaks down their recommendations into four phases.

The plan stipulates that among the first to receive doses of an approved vaccine should be medical workers and first responders, as well as people who may be at particular risk of contracting or suffering serious cases of COVID-19. This may include people who face additional risk either from medical comorbidities, or because of social factors, such as people who must leave their homes to work, use public transportation, or live in multi-generational homes.

“We make a distinction between race and racism," Foege said. "I think people expected us to say, because this disease hurts the minorities more than the majorities, that we would put them first in line. And instead, what we said is, ‘This virus does not recognize skin color at all. But it sure does recognize vulnerabilities. And so let vulnerabilities be the reason that we put people in line first.’"

Some elements of the recommendations seem straightforward, such as including school teachers and staff in Phase 2. Others may cause controversy, such as the fact that people who are incarcerated, such as prisoners, are also in Phase 2.

While Dr. Foege concedes that this may raise some eyebrows, he explains that it’s because these populations have no control over their environments and thus are unable to protect themselves from the virus.

“There may be some pushback from people who don’t want prisoners vaccinated before other people,” he said. "The fact is that prisoners do not have mitigating circumstances. They can’t stay six feet apart ... this situation puts them at high risk.”

The panel’s considerations specifically balanced questions regarding a population’s ability to mitigate exposure and harm versus a particular risk of infection, transmission, hospitalization and death.

The recommendations, now complete, head to the the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and to "state, tribal, local, and territorial (STLT) authorities" for review and consideration.

Still, Dr. Foege said the logistics of distribution — getting the vaccine out to the public to effectively combat the spread of the coronavirus — would be just as challenging as the development of the vaccine itself.

Panelists:

Bill Foege — Former director of the CDC and co-founder of The Task Force for Global Health

Jim Galloway — Lead Political Writer, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution