Caption

“We’ve come a long way from where we were in 2010,’’ says Susan Goico, director of the Disability Integration Project at Atlanta Legal Aid. “The state should be applauded for that. But the work is not done. In supported housing, we have a lot of work to do.’

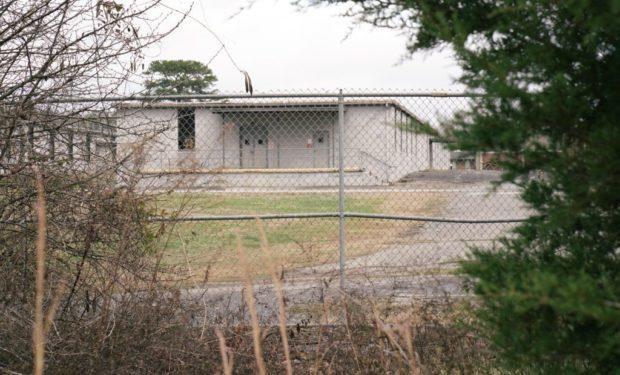

Credit: Georgia Health News