Section Branding

Header Content

The 2020 Election Was Attacked, But Not Severely Disrupted. Here's How

Primary Content

Federal authorities were cautiously optimistic early Wednesday about having made it through voting season without major disruption by cyberattacks or other malign activity — but they cautioned that could still happen in the coming days.

"We're not out of the woods yet," said one senior official with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, who briefed reporters with other U.S. officials on the condition they not be identified.

All the same, officials said, Election Day appeared to have been "just another Tuesday on the internet" and the nation seemed to have cleared some of its biggest milestones in the campaign as normally as practical.

"For the most part today it's been a little boring and that's a good thing — this is kind of one of those best-case scenarios that we would hope for," the senior official said.

Although U.S. officials tried not to be too declarative about what they hoped would be the overall success of securing the 2020 election, they were open about the pride they said they felt in the work of federal agencies and the historically new partnerships between leaders in Washington and throughout the country.

"It's come a long way," said a second top leader, a senior Homeland Security official. "In 2018, a lot of this kind of effort was going on, and it's evolved substantially since then. Going back four years, we have substantially better positions at the federal level and the state level."

For proof, the U.S. officials said, look no further than the huge turnout recorded across the nation — evidence the agency leaders said about how confident Americans are in the security of their votes and the validity of the election.

Tough lessons learned

In 2016, the Russian government unleashed a wave of "active measures" at that year's presidential election, aimed at helping President Trump win office and at hurting his opponent, Hillary Clinton. American officialdom was caught off guard by the magnitude of that offensive and it struggled to identify what was happening and respond.

Those attacks never stopped, but since then CISA, DHS, the FBI and other agencies have worked to build new relationships and invent new practices to defend U.S. election infrastructure and also, as the senior CISA official emphasized late on Tuesday, to make it more "resilient."

American officials acknowledge they can't detect or defeat everything, which is why part of the task since the 2016 election has been working at every level on the ability to adapt to a newly adverse environment.

The official used the example of problems with electronic pollbooks in a small number of places. County leaders had paper records on which to fall back and they were able to keep voting underway. Preparedness was rewarded, the senior official said, even though the cyber-disruption wasn't caused by a foreign actor.

Going on the attack

American operatives also have gone on offense, U.S. officials say.

The cyber-troopers of U.S. Cyber Command, which operates under the Defense Department, are able to "hunt forward" and surveil the work of Russian and other foreign cyber-operatives. That helps American authorities identify the targets they've selected within the United States, take note of their practices and even study the malware they use, which helps bolster cyber-defenses at home, officials say.

The U.S. officials who briefed reporters on Tuesday declined to go into detail about precisely what Cyber Command has been doing against Russian, Iranian and other counterparts this week or earlier ahead of Election Day.

Transparency and disclosure elsewhere, however, are now arrows in American officials' quiver — a sharp contrast to earlier stages in the cyber-game when even local or state entities that had been victims of attacks weren't necessarily read in about what Washington knew.

CISA and the FBI have posted a number of public bulletins about prospective cyber-dangers to U.S. elections infrastructure or the information environment, likely the result of action by CYBERCOM and the National Security Agency as well as new surveillance about what's taking place within American networks.

And they're talking about what they see: Authorities took about 27 hours from the point at which they learned about Iranian spoof-email intimidation attacks to attributing them to announcing them in an unusual news conference with Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe and FBI Director Christopher Wray.

That followed earlier declarations by Wray about the speed with which authorities now move in disrupting cyber-interference.

Authorities' goal is to deny foreign spreaders of disinformation, for example, the ability to try to gain credibility by building up a body of work on social networks or their own websites. When the FBI detected such a scheme that involved Facebook, the bureau acted as swiftly as possible to try to snuff it out, Wray said.

Americans likely aren't free from this kind of mischief in the nation's political life and foreign interference still could surge in the coming days or weeks, the senior CISA official warned on Tuesday night.

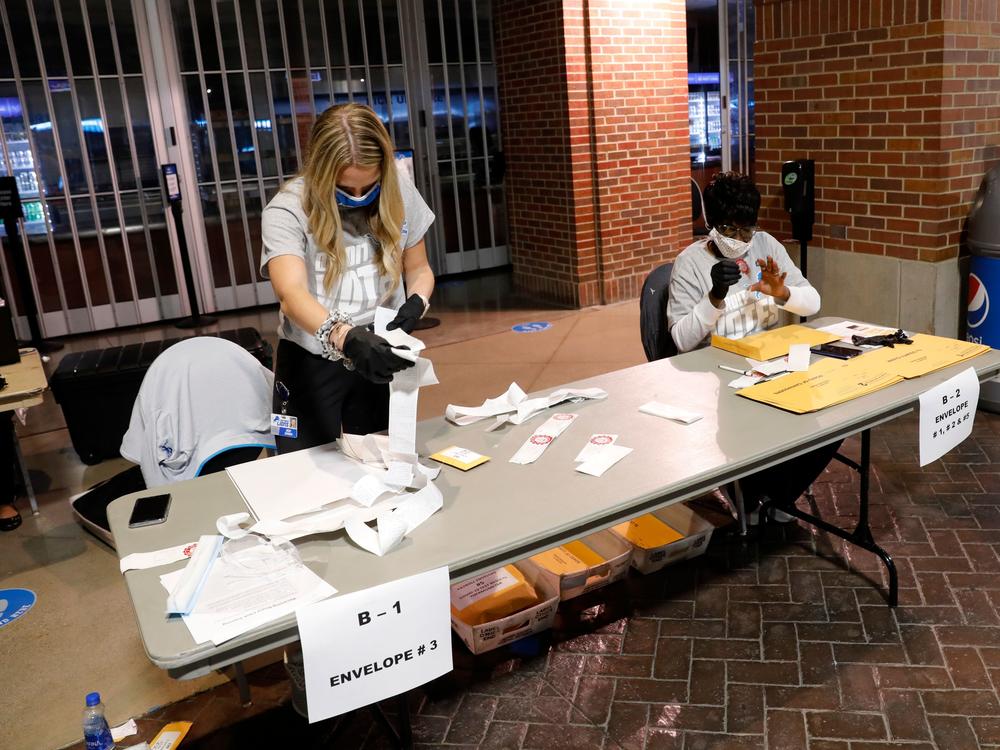

Key precincts in the key states of Michigan and Pennsylvania aren't expected to report results until Wednesday or later, for example — and the longer there is uncertainty about the count in those or other places, the more ripe the environment for false and misleading information or other such action, U.S. officials warn.

"Voting, counting, certification — the attack surface for disinformation extends well into the next month or two," the senior CISA official said. "There is no spiking the football here. We are acutely focused on the mission at hand."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.