Section Branding

Header Content

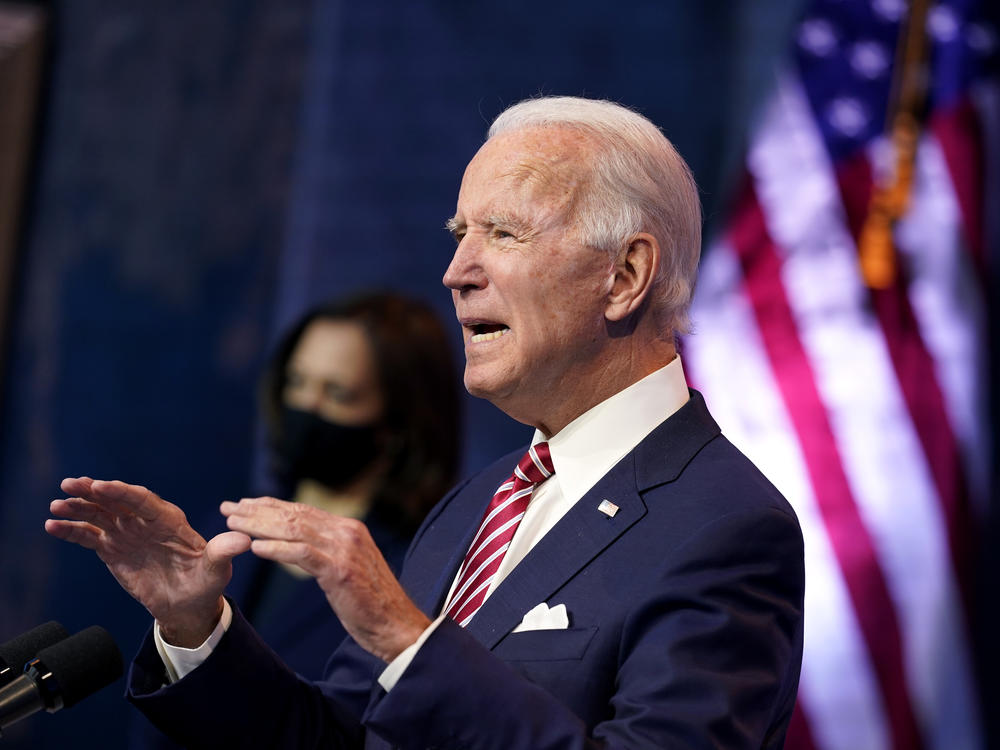

What Joe Biden's Presidency May Mean For Afghanistan

Primary Content

The lone customer at the Simple Café in Kabul has high hopes for America's president-elect.

"Biden won't withdraw American forces from Afghanistan. He'll stay and fight the Taliban," says Sakina Hussaini, a 23-year-old arts student.

She gestures to the empty cafe; it used to be a popular hangout. Now, most people are staying home because of an uptick in deadly car bombings, gunfights and other attacks on civilians across the capital and the country.

"Trump was not beneficial for our country," says Hussaini, who accuses the U.S. president of emboldening the Taliban by overseeing a peace agreement with them, signed in February.

That deal includes provisions for a conditional withdrawal of U.S. forces after nearly two decades at war in Afghanistan. If the deal goes to plan, they will have fully withdrawn by next spring.

But the White House appears to be accelerating its drawdown, creating fresh uncertainty over the situation Joe Biden will inherit on Jan. 20.

On Tuesday, Acting Defense Secretary Christopher Miller announced the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan will be cut to 2,500 by Jan. 15. There are currently about 4,500 U.S. troops in the country.

Afghan officials warn such a move could plunge their country further into upheaval and serves as a signal to the Taliban that they need not honor their commitments.

"We don't want the U.S. to stay here forever," says Javid Faisal, a political adviser to the Afghan National Security Council, "but we also want the withdrawal to be responsible, and don't expect our ally to burn the house when it leaves."

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg warned in a statement on Tuesday that a hasty withdrawal could risk Afghanistan "becoming once again a platform for international terrorists to plan and organize attacks on our homelands," saying the Islamic State "could rebuild in Afghanistan the terror caliphate it lost in Syria and Iraq."

In an apparent message to Washington, he said: "We went into Afghanistan together. And when the time is right, we should leave together in a coordinated and orderly way. I count on all NATO allies to live up to this commitment, for our own security." NATO has fewer than 12,000 troops in Afghanistan.

As part of the deal the U.S. signed with the Taliban, the insurgents pledged not to harbor terrorists who could attack the U.S. and its allies. They also agreed to negotiate with the Afghan government, something they earlier had refused to do.

But peace talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government have been bogged down in procedural disputes. And attacks — many by the Taliban — against Afghan civilians and security forces have only intensified in recent weeks.

A senior Afghan government negotiator, Nader Nadery, tells NPR that he hopes the incoming Biden administration will reassess the U.S.-Taliban deal, "to look at some of the conditions and realities on the ground and to see how, and if needed, what kind of recalibration of this process may be required."

But some analysts see little likelihood of any major changes. The president-elect has a clear, years-long record of opposition to America's sprawling involvement in Afghanistan.

"I think those hopes for a change in direction are likely to be short-lived," says Elizabeth Threlkeld, the South Asia deputy director at the Washington-based Stimson Center.

"I do expect that we'll see a change of tone," she says. It will "become a little bit more multilateral and measured. The process won't feel perhaps so tentative, quite so up in the air, depending on the tweets of the morning."

Biden's own record — particularly as vice president to Barack Obama — helps illuminate how he may act once he is sworn in.

"Biden was the most senior dissenting voice against a surge in Afghanistan back in 2008 and 2009," says Andrew Watkins, senior analyst for Afghanistan at the International Crisis Group. "He remained insistent throughout the last decade that bringing American troop numbers down to just a few thousand and really only focusing on targeted strikes of the very worst of the very worst threats to regional and American security was the only thing that the U.S. should be doing in Afghanistan."

Biden has spoken in favor of keeping a small counterterrorism force in Afghanistan. Retaining even a small contingent of troops, though, could unravel the U.S. deal with the Taliban, who insist all foreign forces must leave within the agreed spring 2021 time frame.

In a statement reacting to the U.S. election, the Taliban expressed commitment to "positive future relations" and held up the February agreement "as a powerful basis for solving the Afghan issue," but warned against "war-mongering circles, individuals and groups that seek to perpetuate the war and to keep America mired in conflict."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.