Section Branding

Header Content

Pandemic Takes Toll On Children's Mental Health

Primary Content

As a toddler, Kenley Gupta stopped speaking after her mom died. Over the years, she recovered from the anxiety disorder, called mutism, but in March the 8-year-old went silent again.

The change occurred soon after her school shut down. Kenley was shocked when her school closed.

"I was really sad I couldn't see my friends," she said.

She was normally a social butterfly and a good student. But after the pandemic forced the school to adopt full-time distance learning, Kenley often crumpled into a ball and hid under her blanket. She would clutch Green Guy, her favorite stuffed animal. Most of the time she refused to talk. The few words she uttered were expressed in Green Guy's cartoon voice.

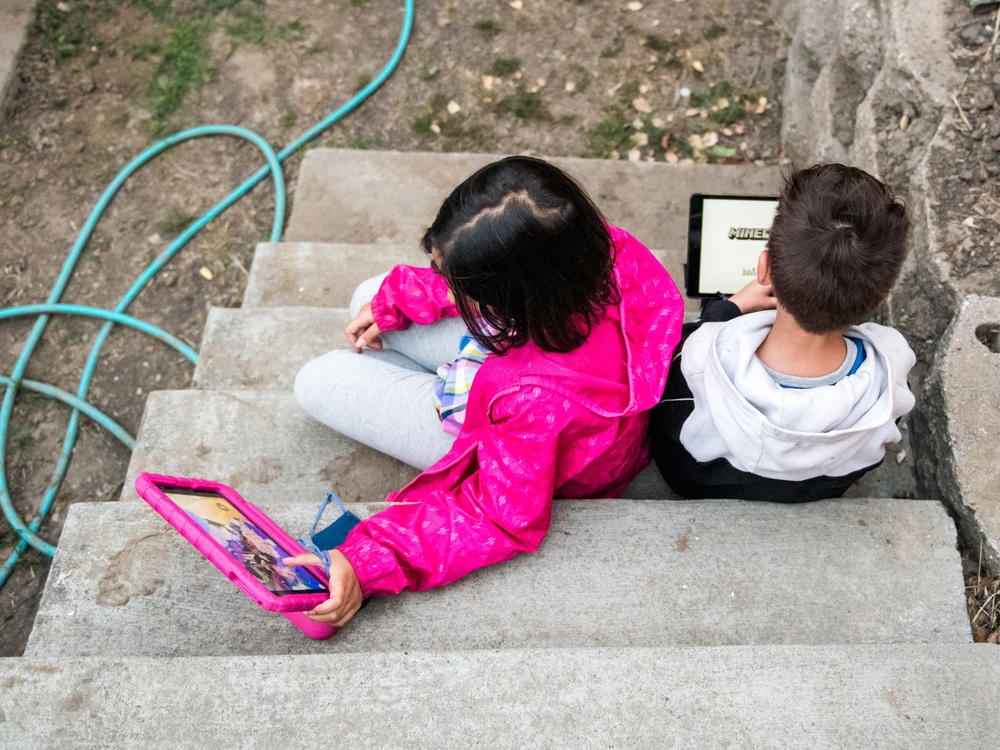

Instead of logging onto Zoom for classes, she spent much of the day gaming — glued to a hot pink iPad. She also stopped drawing and started to eat more.

"There was a kind of almost compulsive snacking that I had never seen before," said Jay Gupta, Kenley's dad.

As a single father, he's struggling, too. Gupta is trying to juggle his job as a philosophy professor at a local college and keep Kenley's twin brother, Anakin, on track as well. Anakin doesn't like distance learning either.

"I much prefer real school because I'm an energy boy," he said. "Home school, I just sit on the couch and say, 'Blaah.' "

Anakin's mental health hasn't declined during the lockdown, but the 8-year-old did fall behind in his schoolwork as the months passed.

"I really felt like I was out at sea," his father said. "At some point, I gave up."

Alarming trends

Even before the coronavirus hit, mental health problems such as depression and anxiety were on the rise in children ages 6 to 17, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research shows social isolation can make these symptoms worse.

Currently, there's little hard data about how the pandemic is affecting children's mental health, mostly because the outbreak is still unfolding and research takes time. The little that scientists have measured is worrisome.

A national survey conducted in the spring of 3,300 high school students found nearly a third reporting they were unhappy and depressed "much more than usual" in the past month. Almost 51% said they felt a lot more uncertainty about the future as well.

Overseas, in a survey of 1,143 parents measuring the effects of the lockdowns in Italy and Spain, nearly 86% reported changes in their children such as difficulty concentrating and spending more time online and asleep, and less time engaging in physical activity. A study of 2,330 schoolchildren in China found both anxiety and depression rose compared with rates seen in previous investigations.

There's plenty of anecdotal evidence to corroborate these trends.

"We see high levels of anxiety," said Saun-Toy Trotter, a psychotherapist at University of California, San Francisco Benioff Children's Hospital in Oakland, "high levels of depression."

Her school-based clinic recorded more youth suicide attempts in the first four weeks of the pandemic than it did in the entire previous year, she said.

"They're giving up hope," Trotter said. "There's nowhere to go. There's nothing to do. There's nothing to connect with. There's just deflatedness."

Trotter advises parents to check in often with their children, listen closely and set routines. She also advises parents to take care of themselves.

"Give yourself as much permission as possible to relax," she said. "Rest. Reset. Restore."

Schools and community organizations are also learning how to support students through virtual events, telehealth sessions and socially distanced activities. Trotter cites the working farm at Castlemont High School in Oakland.

"There are students who garden there three days a week, growing kiwis and red peppers," she said.

She quoted one teenager who was looking on the bright side. " 'If it weren't for COVID, I wouldn't be sticking my hands in the dirt for the first time,' " she said.

Finding resilience

The Gupta family turned a corner over the summer when the twins enrolled in a daily outdoor camp. Within weeks, Kenley rebounded and was back to her old self.

"It is notable that her mood took a 180," her father said. "She's a different person."

The increased social interaction paved the way for a soft landing when the twins returned to distance learning in the fall. Both kids are in therapy. Kenley recently started drawing again.

She still sulks, battling a kind of internal silent storm, as her father describes it. But Gupta is discovering new ways to help Kenley cope. For instance, if someone in the family sits next to her during Zoom classes, she pays closer attention. Just the simple presence of someone familiar keeps her anchored.

Gupta looks forward to the day when Kenley is supported by her teachers in person again.

"I'm all for opening the schools," he said, as long as it's done safely.

Copyright 2020 KQED. To see more, visit KQED.